More FDR for Germany

Even hawkish German economists are finally discussing changes to the debt brake but, unfortunately, a lot more needs to happen before this discussion enters the political arena. Perhaps Germany needs a lesson from Franklin D Roosevelt…

Slamming on the debt brake

Germans love their sacred cows: Driving without speed limits on the highway, lead melting on New Year’s Eve, closed supermarkets on Sundays and, more for the economists, fiscal surpluses aka The Black Zero. This year, the constitutional debt brake, which morphed into the Fiscal Compact for the rest of the eurozone, celebrates its 10th anniversary. Very few feel like partying.

Like many economic views in Germany, the constitutional debt brake dates back to the hyperinflation of the 1920s. Government debts - and later war expenditures - could only be funded by cranking the money press. The lesson was: never repeat! In the constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany, a paragraph was already included in 1949 which allowed the government only to run fiscal deficits in exceptional situations. This paragraph was amended in 1969 to a kind of golden rule, allowing fiscal deficits up to the level of gross investments. Higher deficits were only allowed in case of "disruptions of the economic equilibrium".

However, there was no clear definition of this balance and the door to a rapid rise in government debt was opened. While the debt-to-GDP ratio stood at less than 20% of GDP from 1949 to 1969, government debt increased to 80% of GDP until 2009. Public finances in the federal states also grew unsustainable; in the 1990s there were even a few of those states that were on the verge of bankruptcy.

Against this backdrop, an ageing society with rising government costs and the realisation that out-of-control government debt can lead to turmoil in financial markets along with so-called snowball effects due to rising interest rates, the German government decided in 2009 to limit the annual fiscal balance constitutionally. The debt brake. Since 2016, the federal government may have a maximum fiscal deficit of 0.35% of GDP (adjusted for cyclical effects). The Länder will not be able to have any fiscal deficits from next year onwards.

Disciplinary tool which needs a make-over

Up to now, the debt brake has worked as an excellent instrument for discipline. The federal government is running record surpluses year after year and budget discipline has now become a standard feature in those states. At first glance, the Black Zero is a success story in disciplining politicians. On closer examination, however, it is less attractive: the debt brake is also one of the main reasons for the lack of investment in Germany. This is food for thought among German economic circles right now - even austerity fetishists have become advocates for some changes.

The debt brake is one of the main reasons for a lack of investment in Germany

Rightly so. According to the latest data, German government debt dropped to 60.9% of GDP last year and should fall below the Maastricht threshold of 60% GDP this year, for the first time since 2002. With low interest rates and fiscal surpluses, the debt ratio could fall below 50% within the next five years. In fact, assuming everything else being equal, the government could run fiscal deficits between 1.5% and 2% of GDP for the next five years and the debt ratio would still be stable, at close to but below 60%.

Extremely low interest rates, in particular, are currently the main reason to rethink the ratio of the debt brake. At the very least, the debt brake should get some more breathing space to allow for more investments. This could be done by linking nominal GDP growth to interest rates, a sovereign wealth fund, higher investment-related deficits or other ways. Unfortunately, while the discussion has finally – and far too late – reached prominent economists’ circles, it will still take a while before it will reach politics. The Black Zero is simply too attractive, both as an instrument for discipline but also as an easy campaign promise to fulfil.

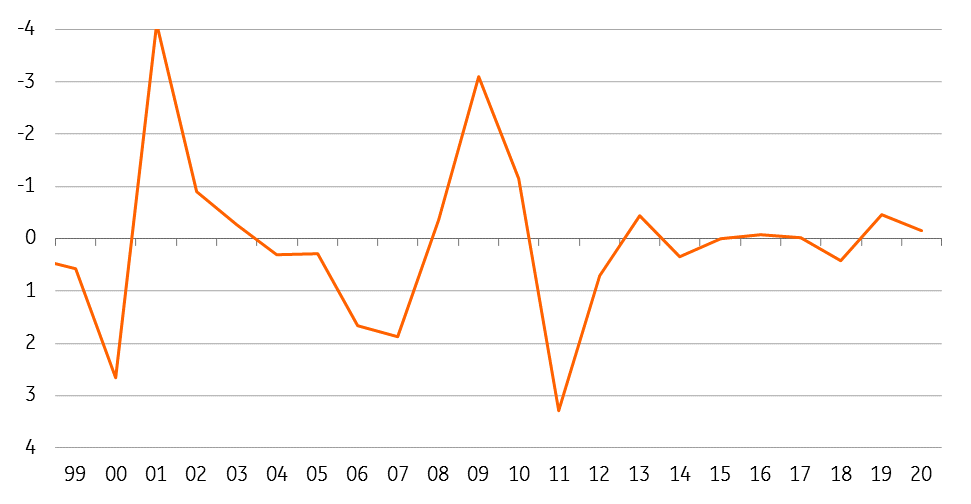

German fiscal stimulus since start of EMU

An FDR lesson for Germany

Germany has shown several times that it can bend or change the rules. It is about time it created more room for investments. Otherwise, future generations might be left with fewer debts but also with sluggish internet, potholed highways and bridges and permanently delayed trains. Germany should learn from Franklin D. Roosevelt who once said that rules are not necessarily sacred, only principles are.

Download

Download opinion

Carsten Brzeski

Carsten Brzeski is the Global Head of Macro for ING Research. Previously, he worked at ABN Amro, the Dutch Ministry of Finance and the European Commission. He is a 2019 JFK Memorial Policy Fellow at Harvard University and member of the Advisory Council on International Affairs for the Dutch government and Parliament. Carsten has studied at the Free University of Berlin, Northeastern University in Boston and Harvard University in Cambridge, USA.

Carsten Brzeski

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more