Brexit: Which countries will be hit most by ‘no deal’?

As the law stands, the UK is set to leave the European Union next Friday- with no deal. And while much of the focus has been on the potential damage to the UK economy, its nearest neighbours will feel the strain, too

It’s still not clear exactly what will happen on 29 March. Prime Minister Theresa May is working overtime to find support for her Brexit deal even as Speaker John Bercow ruled out a third Meaningful Vote on what is essentially the same agreement.

Parliament has voted to request an extension to the two-year Article 50 negotiating period but there is still no clarity on whether this will be granted by the EU or how long it might last. On Tuesday, May ruled out a long delay, which some say could increase the chances of no deal.

There are many ways that a no-deal Brexit could prove disruptive. For services, uncertainty surrounding data sharing, financial market access and future freedom of movement will be particular challenges. In this article, we’ll take a quick look at the problem from a goods perspective. There are two main obstacles:

Some UK exports to EU face substantially higher tariffs

Leaving the customs union could create headaches surrounding rules-of-origin, and will also introduce tariffs on goods. EU-bound shipments will be subject to Brussels’ World Trade Organisation (WTO) tariff schedule – a list of tariffs that apply to countries with whom the EU does not have some form of preferential/free trade deal. The average trade-weighted tariff the UK would have to pay over its exports to the EU is 3.9%. However, there’s a big variation in tariff rates across different products. Apparel, cars and agricultural products tend to face the steepest tariffs. The highest rates are on dairy and agricultural products with ([1]) tariffs for some particular types of products as high as 178%.

[1] Ad Valorem Equivalent Tariffs, are tariff rates, principally, specified as a duty per volume unit (Kg / L / Metric Tone / Etc.) converted to implied Ad Valorem Tariffs.

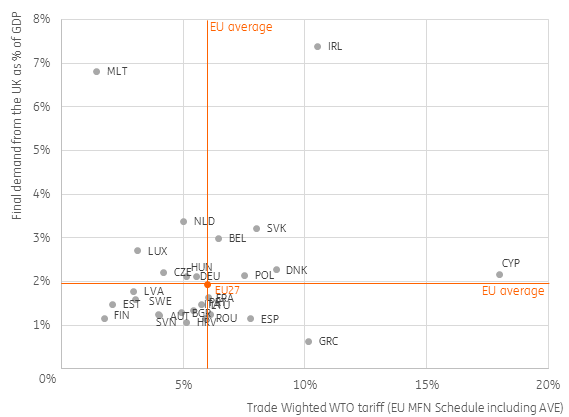

Figure 1: Exposure of individual EU countries

But the UK can slash tariffs on imports

However the UK does not have to respond in kind. The government has already released a temporary tariff schedule, which it will be implementing in case of a no-deal Brexit. Although high tariffs on cars and agricultural products will remain, a significant proportion of tariffs on other products would be sliced to zero. This is a bold decision that would erode the competitiveness of British companies on the local market. If permanent, It would also make it more difficult to strike free-trade deals with the rest of the world, as there would not be much left to offer in terms of tariff reductions.

Sharp tariff cuts are likely to be temporary

With that in mind, these tariffs are unlikely to remain beyond the initial 12-month term. Let’s assume for a minute that the UK ultimately decides to mirror the EU’s list of tariffs. In this case, the average rate that would be applied to EU exports to the UK would average 6%.

However, because the basket of exports to the UK varies significantly from one EU country to the next, this percentage would be different for each member state. Ireland, for example, exports a lot of diary, meat and agricultural products that are subject to higher-than-average duties. For some other countries, the opposite is true. Finnish exports, for example, are dominated by paper and wood products, for which tariffs are typically low.

In addition to trade-weighted average tariffs, some countries trade- either directly or indirectly- with the UK more than they do with other countries. On average, 1.9% of EU GDP depends on final demand[2] from the UK, which appears to be fairly limited, but considerable differences exist among EU countries.

- British final demand accounts for 7.4% of Irish GDP

- Only 0.6% of Greek GDP depends on UK final demand

- About 6.8% of British GDP depends on final demand from the EU

Figure 1 shows which countries are most exposed to a no-deal Brexit through these two channels: composition of exports and the contribution of (in)direct exports to their GDP. The UK’s neighbouring countries: Ireland, Belgium and the Netherlands are particularly exposed. Note that, due to the large share of re-exports in Dutch exports, the trade-weighted tariff for the Netherlands is not fully representative.

Although Malta is also highly dependent on final demand from the UK, this is almost entirely concentrated in the services sector, which is less affected by tariffs. Slovakia, Poland and Denmark also have above-average exposure relative to the EU-27 average. Cyprus has the highest trade-weighted tariff within the EU.

EU-wide, the data shows that mining and quarrying companies are most dependent on final demand from Britain. But mining companies are unlikely to be among the hardest hit by a no-deal Brexit because tariffs for these sectors are generally less than 1%. These goods will also be less affected by frictions arising from the sudden exit from the EU single market. However, it's a different story for automotive companies and food producers, as tariffs on these types of products are much higher and the dependency on British demand is above average as well.

[2] This exposure may be indirect. For example: part of Germany’s exposure is channelled via car parts embedded in cars exported from Slovakia to the UK

Figure 2: 15 European sectors most dependent on British final demand

The impact of leaving the single market

The UK's exit from the EU single market in principle means that European goods will be subject to checks at UK borders to ensure they comply with UK rules. The likely increase in costs could be a reason to refrain from exporting to the UK. Indeed, this could potentially dwarf the impact of tariffs.

Food/animal products tend to be the most heavily scrutinised. As things stand, neither Dover nor Calais have the necessary Border Inspection Posts (BIPs) to provide veterinary checks – although France is in the process of building the necessary infrastructure on its side.

Take the example of fish – the UK exports 81% of what it catches, and imports a significant proportion of what it eats. Given the limited capacity to perform the veterinary/phytosanitary checks, there is the potential for long delays on both sides of the Channel – bad news if you are trying to get fresh food transported quickly.

The UK government has already said there would be no realistic option to perform checks at the Northern Irish border. This may induce more scrutiny from EU customs at the UK borders as this offers incentives for smuggling.

Port frictions will also be a major problem for just-in-time supply chains. The British Freight Transport Association has estimated that for each extra minute a lorry spends at customs in Dover, roughly 30 km (17 miles) of additional queues would form on the major M20/A20 roads. This potentially raises the cost of transport and reduces the viability of lower-value shipments. A similar situation could occur on the French side of the border.

A range of surveys suggests that firms are ramping up contingency planning for a no-deal Brexit. These preparations come at a cost, and in the short-term, this planning process will continue to weigh on investment in the UK and Europe.

Download

Download article"THINK Outside" is a collection of specially commissioned content from third-party sources, such as economic think-tanks and academic institutions, that ING deems reliable and from non-research departments within ING. ING Bank N.V. ("ING") uses these sources to expand the range of opinions you can find on the THINK website. Some of these sources are not the property of or managed by ING, and therefore ING cannot always guarantee the correctness, completeness, actuality and quality of such sources, nor the availability at any given time of the data and information provided, and ING cannot accept any liability in this respect, insofar as this is permissible pursuant to the applicable laws and regulations.

This publication does not necessarily reflect the ING house view. This publication has been prepared solely for information purposes without regard to any particular user's investment objectives, financial situation, or means. The information in the publication is not an investment recommendation and it is not investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure that this publication is not untrue or misleading when published, but ING does not represent that it is accurate or complete. ING does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication. Unless otherwise stated, any views, forecasts, or estimates are solely those of the author(s), as of the date of the publication and are subject to change without notice.

The distribution of this publication may be restricted by law or regulation in different jurisdictions and persons into whose possession this publication comes should inform themselves about, and observe, such restrictions.

Copyright and database rights protection exists in this report and it may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any person for any purpose without the prior express consent of ING. All rights are reserved.

ING Bank N.V. is authorised by the Dutch Central Bank and supervised by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). ING Bank N.V. is incorporated in the Netherlands (Trade Register no. 33031431 Amsterdam).