Real wages in the eurozone will return to modest growth next year

Since the recovery from the financial crisis, nominal wage growth in the eurozone has been sluggish. This is often attributed to weaker trade unions. But wage growth in real terms is higher now than it was before the crisis. We expect a decline in 2022, but real wages will grow in 2023, although probably only modestly

Nominal wages suggest disconnect with labour market

According to the European Commission, the eurozone unemployment rate has declined to levels below the natural rate of unemployment, and the vacancy rate is at an all-time high. But gross wage growth in nominal terms has only recently begun to accelerate after ending 2021 with a year-on-year increase of just 1.5% in the fourth quarter. This was a historic low. In the first quarter of this year, wage growth was 3%, but that was partly made up of one-off pay bonuses.

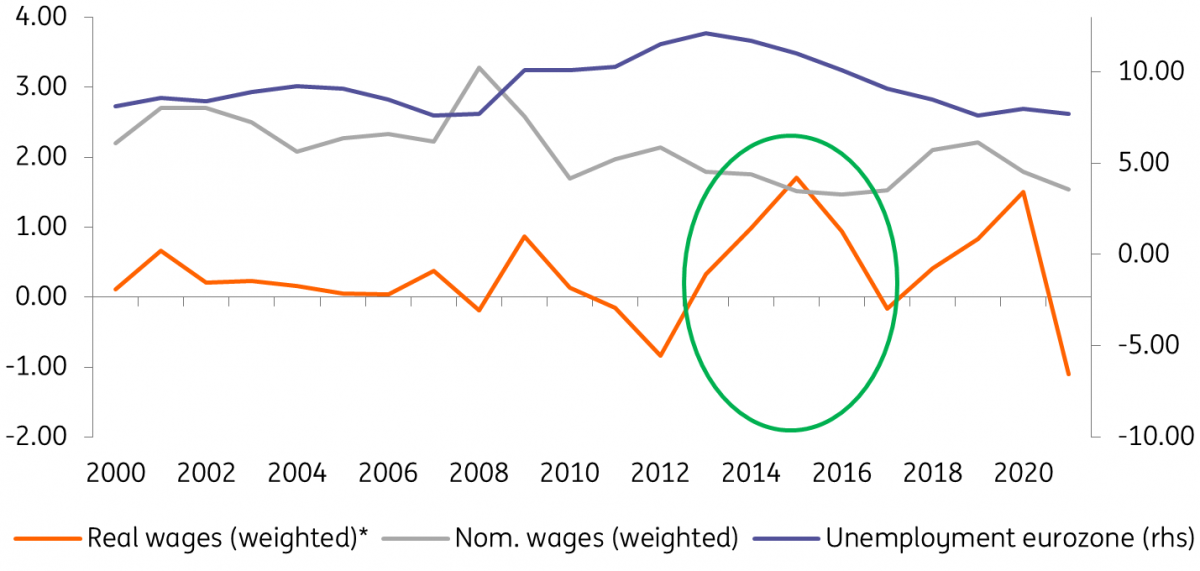

Last year wasn't the only year in recent history with low growth in nominal wages. On average, the yearly wage increase after the global financial crisis (GFC) was only 1.8%, compared to 2.5% during 2000-09. Nominal wage growth was especially low during the years 2014-16 (chart 1).

The slowdown in average nominal wage growth is not that surprising. After all, the economy – measured by the average size of the output gap and unemployment – performed much better in the years before the GFC than in the years after, when the eurozone had to face the euro crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, what is surprising, at first sight, is that while unemployment started to come down from 2014 onwards, it took several years before nominal wage growth increased (chart 1).

Unemployment and the divergent development of nominal and real wages

Real wage growth shows quite a different picture

Nominal wage growth is, however, a misleading indicator to judge whether trade unions have performed well in wage negotiations. In the end, it is real wages that are interesting for employees because they are adjusted for inflation and therefore more directly related to their purchasing power (chart 1).

Net real wages are even more interesting for employees. However, in this article we want, among other things, to determine whether pay rises in the private sector reflect the changes in the balance between supply and demand in the eurozone labour market. Since net wages are also determined by changes in income tax and social security contributions set by the government, the development of gross wages is a better indicator to find an answer to our question.

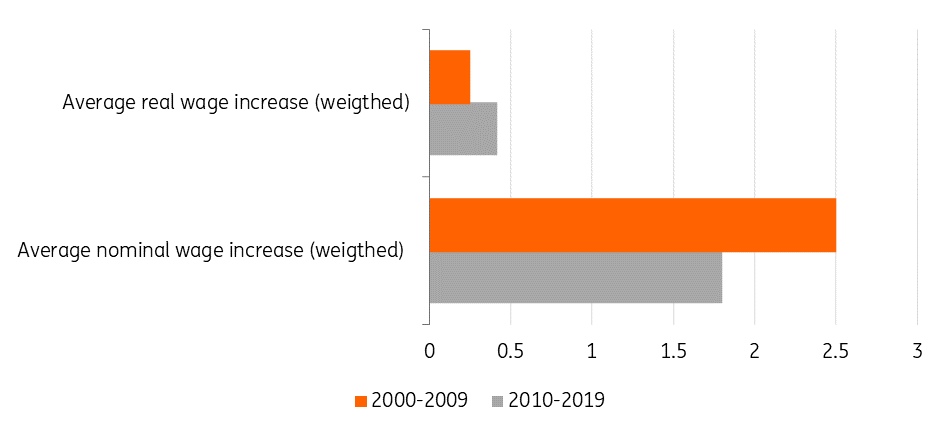

Looking at the development of real wages, it is striking that average real wage growth post-GFC was higher than pre-GFC. While average nominal wage growth per year declined after the crisis, average real wage growth almost doubled from 0.24% per year up to 0.42% (chart 2).

This is remarkable because the conditions in the economy and in the labour market, measured by the unemployment rate and the output gap, were less favourable in the years after the GFC than in the years before the GFC.

Eurozone nominal wage growth down but real wage growth up

Money illusion

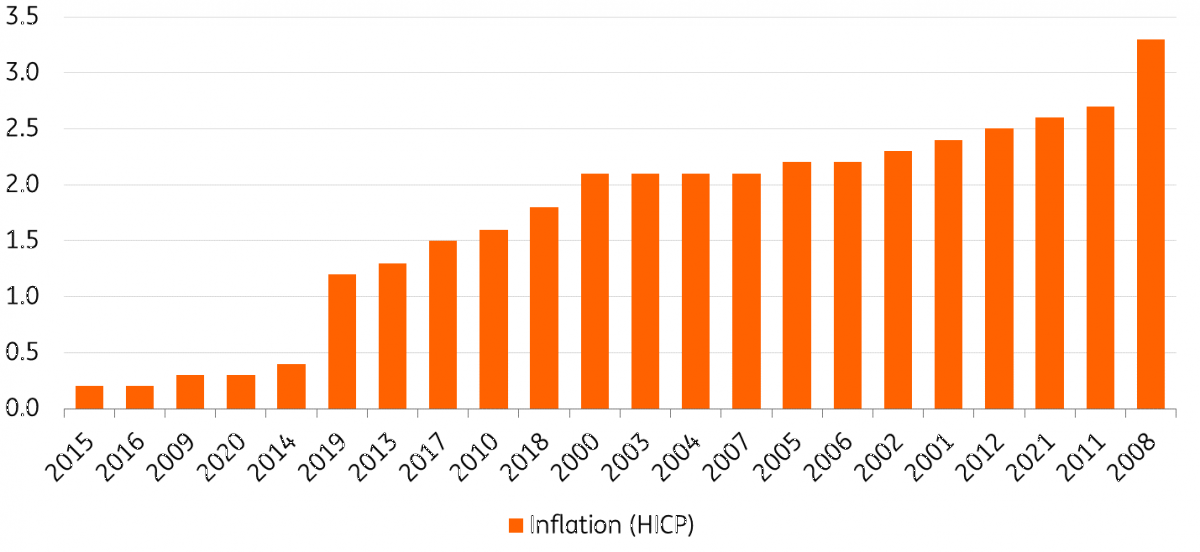

It is the very low inflation between 2014- 2016 (between 0.2% and 0.5%) that mainly explains the low growth of nominal wages since the GFC and causes the large difference between the development of nominal and real wage growth. These three years rank in the top five of the lowest inflation years of this century (chart 3). If inflation had been higher, wage demands and nominal pay rises would have been higher too.

Commentators that label the wage development in the eurozone as 'sluggish' and attribute this to a weakening position of the trade unions, base these conclusions on the wage development in nominal terms instead of real terms. This is understandable because of the fact that the media focuses on nominal pay rises, but incorrect.

Looking at real wages the performance of trade unions has not been bad at all. It should be said however that the favourable outcome of the wage negotiations in real terms during 2014- 2016 was in part the result of the fact that inflation in reality was better (lower) than was expected at the time that wage demands were set.

The second half of the last decade has been characterised by all-time low eurozone inflation

Because of the focus of commentators on nominal wages instead of real wages, a classic case of the ‘money illusion' has emerged; low nominal wage increases are incorrectly labelled as weak bargaining results that are at odds with the economic recovery and the improvement in the labour market.

But, on the other hand, in 2017 and 2018, when inflation was not so low, the real wage outcome did not reflect the improvement of the economy and the labour market. Real wages decreased in 2017 and showed limited growth in 2018 (chart 1). And the fact that unions have not been able to convert (all) labour productivity growth into higher wages (chart 4) also indicates a loss of bargaining power, particularly because this didn't only happen in economically weak years but also in strong years during which jobs were not generally at risk. For example, in 2006, 2007 and 2017, employment was growing but the unions did not succeed in converting productivity increases into extra pay rises.

Eurozone real wages cannot keep up with labour productivity

Weakening position of trade unions cannot explain wage developments

Most trade unions have continuously lost members since the start of the century, particularly since the GFC. And, measured by the number of striking days per 1,000 employees, data from the European Trade Union (ETUC) shows that eurozone trade unions have been less militant since the GFC than before the GFC.

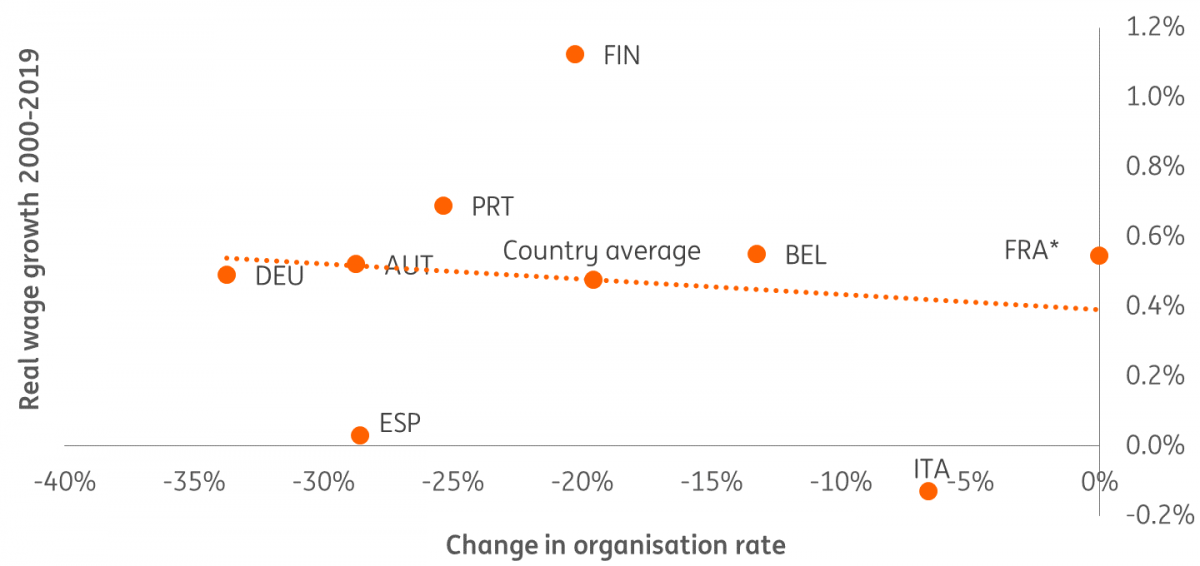

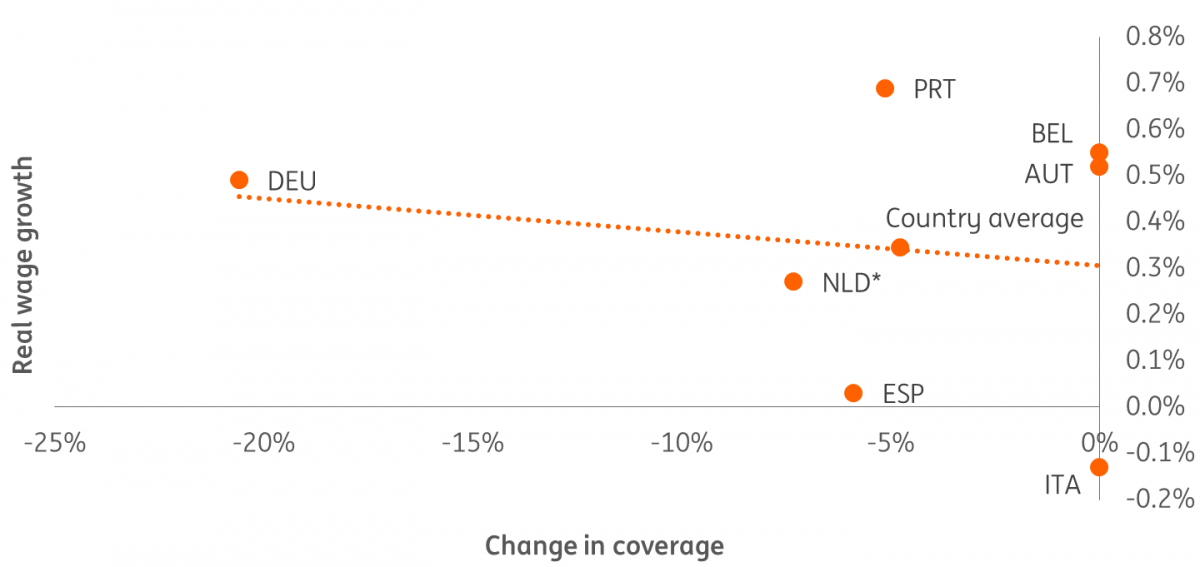

Cross-country analysis, however, does not support the view that declining union membership leads to weaker bargaining results. As chart 5 shows, real wage growth in countries with a relatively large loss of membership is not lower than real wage growth in countries with a smaller loss of members.

As long as employers' organisations are willing to negotiate collective bargaining contracts with trade unions, the unions maintain bargaining power. There are some examples of employers (organisations) that succeeded in substituting the traditional trade unions as negotiation partners with new unions or workers' councils, but in general, the traditional unions still hold ground, despite the loss in union membership.

Unions with more membership losses don't show lower real wage growth

Union bargaining power (with a few exceptions) has also been strengthened by the fact that many European governments usually extend industry deals between unions and employer's organisations to all companies that are part of that industry. This phenomenon also helps to explain why a loss of union membership rates in a sector does not ‘mechanically’ result in less say over working conditions and pay in that sector (chart 5).

Differences in the change of the coverage rate of collectively-bargained contracts don't relate to differences in real wage developments 2000-19

Outlook for wage growth

2022 was expected to be the year when the economic recovery from the pandemic and the tightness in the labour market would translate into an improvement in real wages. But this year is turning out to be a difficult one for real wages because inflation has been accelerating surprisingly fast to levels not seen since the 1970s.

In our January piece, we forecast nominal wage growth to accelerate from 1.5% last year to 3- 3.5% this year. The economic outlook has deteriorated since, given the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war. We, nevertheless, still expect nominal wages to accelerate this year and not lose much ground next year because of the tightness of the labour market in the eurozone and because high inflation this year pushes up wage demands in both years. However, the economic slowdown will, with the usual time lag, start to put downward pressure on the bargaining results in the future.

Thus far, wage demands and bargaining results in 2022 are accelerating as expected. The German union IG Metall is in the process of preparing negotiations for the German metal industry but has already announced that the demand for wage increases could be 3.5% or somewhat higher. Steel workers' wages in Germany will grow by 4.4% on a 12-month basis, as a result of the recently-agreed collective bargaining contract.

Some countries where collective bargaining has already resulted in a considerable amount of contracts show a clear upward trend in the outcome of wage negotiations. In January, the average nominal wage increase in the Netherlands, for example, was 2.6% on a 12-month basis. Collective bargaining contracts in May showed an average increase of 3.8%. Austria also shows increasing wage growth, for example in the electricity sector where wages will rise by 3.5-4% on a 12-month basis.

In France and Spain, wage agreements also show a clear increase in wage growth compared to last year. In Italy, wage growth remains at very low levels according to the latest data.

For 2023, much will depend on the question of how long the economic setback and high inflation, due to the war, continues. ING expects no recession for the whole of the year but GDP growth will slow down well into 2023. Inflation will probably peak in the current quarter at 7.7% and then steadily come down in the direction of the target of 2% towards the end of next year. Inflation will diminish because, among other things, we expect oil and gas prices to increase less next year than this year and because we don’t expect a wage-price spiral. Given the current difficulties for many companies to fill vacancies, we expect employers to pursue labour hoarding during the economic slowdown so that unemployment will not rise much.

The decline of inflation next year and the continuation of low unemployment rates make it possible for real wage growth to recover. In other words, we expect that unions will be able to negotiate wage increases in 2023 that better reflect the conditions of the labour market. But given our expected inflation rate of 2.5%, real wage growth in 2023 will be modest.

Download

Download article"THINK Outside" is a collection of specially commissioned content from third-party sources, such as economic think-tanks and academic institutions, that ING deems reliable and from non-research departments within ING. ING Bank N.V. ("ING") uses these sources to expand the range of opinions you can find on the THINK website. Some of these sources are not the property of or managed by ING, and therefore ING cannot always guarantee the correctness, completeness, actuality and quality of such sources, nor the availability at any given time of the data and information provided, and ING cannot accept any liability in this respect, insofar as this is permissible pursuant to the applicable laws and regulations.

This publication does not necessarily reflect the ING house view. This publication has been prepared solely for information purposes without regard to any particular user's investment objectives, financial situation, or means. The information in the publication is not an investment recommendation and it is not investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure that this publication is not untrue or misleading when published, but ING does not represent that it is accurate or complete. ING does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication. Unless otherwise stated, any views, forecasts, or estimates are solely those of the author(s), as of the date of the publication and are subject to change without notice.

The distribution of this publication may be restricted by law or regulation in different jurisdictions and persons into whose possession this publication comes should inform themselves about, and observe, such restrictions.

Copyright and database rights protection exists in this report and it may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any person for any purpose without the prior express consent of ING. All rights are reserved.

ING Bank N.V. is authorised by the Dutch Central Bank and supervised by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). ING Bank N.V. is incorporated in the Netherlands (Trade Register no. 33031431 Amsterdam).