More of the same policies from Bank of Japan as the world changes

Bank of Japan remains committed to its ultra-loose monetary policy for at least the next 14 months, but there remain questions about whether a policy that has arguably failed to achieve its objectives for years should continue to be followed

Bank of Japan back under the spotlight

It has been a very long time since Bank of Japan (BoJ) was interesting enough to warrant any significant comment, but it is back in the limelight again.

BoJ policy has not deviated in any substantial way for many years, though there has been a creeping evolution of policy over the past decade including the adoption of yield curve control in 2016. The range of tolerated deviation around the zero yield target on the 10Y government bond (10Y JGB) has also been marginally tweaked on several occasions, mostly to accommodate market volatility rather than to demonstrate a discrete shift in the stance of policy. The last time this was done was March 2021 when the range was widened from +/-0.2% (itself an expansion from the original 0.1%) to +/-0.25% – this was the last time global bond yields pushed notably higher.

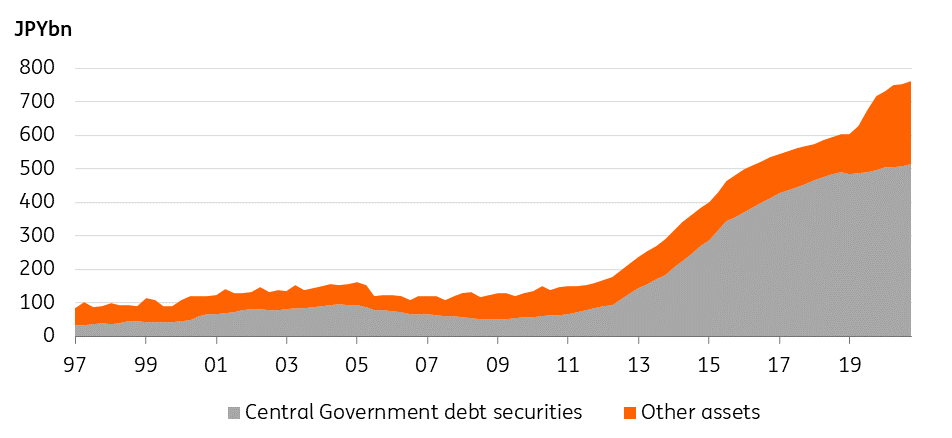

The adoption of yield curve control in 2016 took some pressure off the prevailing Qualitative and Quantitative Easing (QQE) programme which the BoJ had earlier relied on. That policy committed to buying certain quantities of bonds and other assets (exchange-traded funds, corporate bonds and Japan's real estate investment trust). The addition of a 10Y JGB yield target in 2016 was itself a marginal adjustment to the policy. The numerical targets for JGBs remained but were quietly dropped in January 2021 to be replaced by a commitment to purchases “without an upper limit” to achieve the zero interest rate target (numerical targets for the other asset types remained).

Bank of Japan asset holdings

Dropping numerical purchase targets reflected

In reality though, all that was happening was that the policy was being adjusted to reflect the fact that it took far fewer purchases in practice to achieve the BoJ’s target than had ever been envisaged. That had been evident for some time.

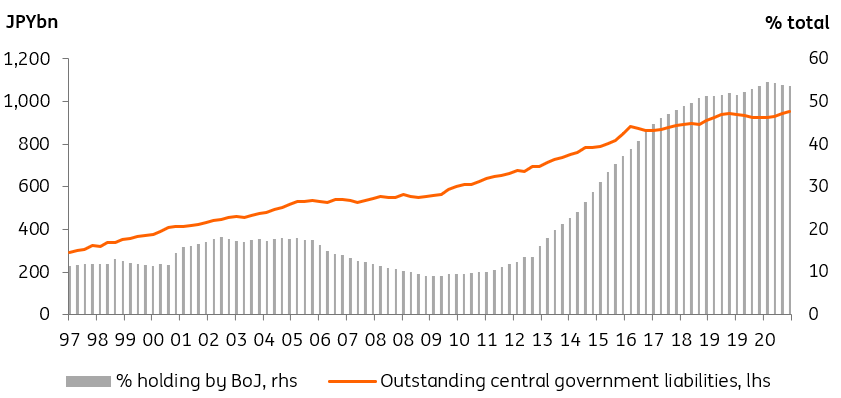

That experience probably also reflected the fact that the BoJ already owned more than 50% of all outstanding central government bonds. The available pool of assets for them to purchase had become very thin and it probably took very little purchasing by the BoJ to keep bond yields close to zero.

There were nevertheless widespread accusations of “stealth tapering” (including from us), though this was a slightly unfair reaction to the fact that this target was becoming incrementally easier to achieve.

In the current situation, JGB yields have again drifted higher and threatened the top of the 0%+/- 0.25% target band for the policy. The culprit is rising global bond yields, especially US Treasury yields amidst expectations of aggressive rate rises from the Federal Reserve and some other global central banks.

BoJ holdings of central government securities

JGB yield rise nothing to do with domestic situation

There is literally no domestic Japanese content to the current rise in JGB yields. Japanese national inflation is admittedly running above its previous trend. But at 0.8%year-on-year (will likely decline to 0.6%year-on-year when January data are released later this month) and a core rate that looks as weak as ever at -0.7%year-on-year, domestic inflation is just not a factor. There will be some pick up in year-on-year headline rates over the coming months. But this will be a pure base-effect from weakness the previous year, and has no policy implications (though no doubt policymakers will try to portray it as evidence of policy success).

Economic growth is not a factor either. Japan had a mediocre growth performance in 2020 when the pandemic started, shrinking by 4.5% for the full year. The second and third waves of Covid meant that instead of bouncing strongly in 2021, Japan only recovered some of that lost ground, growing a mediocre 1.8%. Aggressive fiscal stimulus should see Japan’s GDP beat 2% growth this year, but the economy may only be recovering pre-pandemic levels of activity and will likely remain well off where it would have been in the absence of Covid – a distinctly sub-par performance compared to many other G-7 economies.

So now the BoJ is showing some discomfort with the yield of 10Y JGBs, offering to buy unlimited amounts at a fixed rate equal to the upper limit of its target range (0.25%). Purchases due to take place on Monday 14 February did not in the end see any purchases as rising geo-political risk drove investors into Japanese yen-denominated assets (including 10y JGBs) and pushed yields back down to only about 0.21%.

The BoJ remains an oddity among central banks right now, clinging to its policy approach while other central banks around the world are adjusting to a new normal. Japan’s domestic conditions may support their different approach. But the commitment to retain an ultra-loose monetary policy stance until after BoJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda steps down next April seems inflexible against the backdrop of a shifting global macro and market environment.

Japan's 'inflation' bounce in 2022 is only a base effect and won't last

Is the zero yield target really helping?

And this raises a final question. Is a target for zero bond yields even helping an economy with an ageing population with substantial savings? Has it ever been the right policy?

It has never been entirely clear to this author that the economic impacts of monetary policy are linear, or even that ever-lower rates deliver always greater stimulus, even if at diminishing rates. The concept of a “balancing point” for interest rates is not quite mainstream, with central banks like the European Central Bank (ECB) still maintaining that zero or even negative rates do more good than harm. But it is no longer monetary heresy to dare to suggest that such balancing points do exist, and may even do so at low but positive nominal rates.

Much clearer is that the BoJ’s current policy regime has consistently failed to shift Japan out of its low growth, low inflation trap and that simply repeating versions of a failing policy in different forms seems destined to keep delivering the same sub-optimal results in terms of growth and inflation.

The last domino doesn’t need to fall to push foreign yields up

It is impossible to talk about the ‘lower for longer’ trend in global rates without talking about the actions of a handful of ultra-dovish central banks. The largest of them, the ECB and the BoJ, have played an instrumental role in extending the trend towards lower long-term yields globally even as the Fed hiked in 2015-18. This month, the ECB has taken the first step on its way to policy normalisation, the BoJ is likely to be a long way behind.

We would argue that the BoJ doesn’t need to tighten policy outright to at least ease the downward pressure on other DM rates markets. The first question is whether, by keeping the size of its bond portfolio unchanged, the BoJ still exerts a net easing effect on global financial conditions, or whether its effect is better described as neutral.

Japanese buying foreign bonds tends to follow local easing cycle

Intuition suggests that as it stops squeezing domestic investors out of the JGB market, the spillover into other bonds markets also grinds to a halt. This may be true but this is only one part of the story. We suspect Japanese investors are as liable to be ‘crowded out’ of the JGB market, as they are to be ‘crowded in’ to foreign bond markets by ECB and Fed purchases. In practice, this means greater confidence in buying foreign bonds in phases of global easing, but also reluctance when policy discussion turns to tightening as it does currently.

We expect higher JGB yields, and the rising cost of FX hedges to drive some Japanese investors out of US Treasuries

The second question to answer is whether the JGB market, even with higher yields, and potentially a steeper curve if the BoJ continues to cap 10Y, can be the recipient of repatriation flows. We think this argument cuts both ways. On the one hand, we expect higher JGB yields, and the rising cost of foreign exchange (FX) hedges to drive some Japanese investors out of US Treasuries. On the other, lower liquidity in the JGB market raises doubts about its ability to absorb the extra flow.

The full effect of any policy turn at the BoJ is likely to only show in the longer term, but the fact that other central banks are close to tightening means a gradual lifting of downward pressure exerted by the BoJ on foreign bond markets.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more