Four crucial questions for Eurozone leaders to answer

European leaders made little progress in answering profound questions about the Eurozone's future at their June summit. But ensuring economic sustainability should be a priority, says ING's Chief Economist, Mark Cliffe

The future of Europe

Although some progress has been made over the years, we're potentially only one recession away from the fragmentation of the Eurozone. Building up Europe's resilience to future economic setbacks should be at the top of the agenda for Europe's leaders. Prompted by a recent ING-sponsored Future Europe conference, where politicians and policy-makers tackled some of the pressing issues, here are four questions that Eurozone leaders should be giving answers to.

Is some form of fiscal capacity necessary to preserve the Economic and Monetary Union?

Greater fiscal capacity – an expanded budget - is not essential but it would be very helpful. Since reform, and therefore structural flexibility could take years to have a big enough effect, developing a substantial countercyclical fiscal capacity would be timely. Governments would have greater room to fight downturns by temporarily relaxing fiscal policy. Agreement on this would also have a powerful signalling effect. By increasing the confidence in the sustainability of European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), it might increase investment and reduce the risk of speculative attacks on it.

But size matters: the precise form of the fiscal capacity is less important than the strength and scale of the political commitment to it. This is important to give investors’ confidence in the sustainability of the Eurozone. As to what type of fiscal capacity is envisaged, there are a number of ideas that are being considered:

- Prioritising investment is a good idea in principle, but the efficiency in implementation in the past has been questionable.

- An unemployment insurance fund is another worthwhile idea because it has a redistributive quality that is both economically and politically appealing.

- A euro-wide safe asset would not only spread risk but also reduce risk by making it less likely that self-fulfilling market panics about debt sustainability break out in the first place.

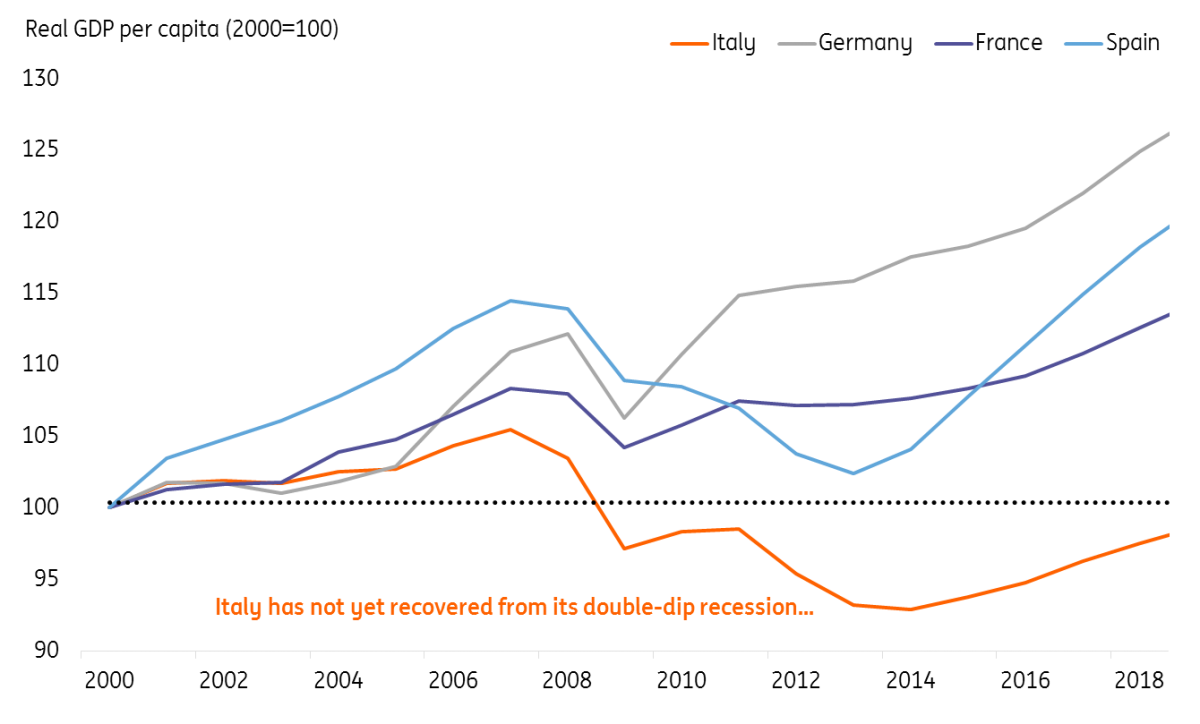

Divergence in real incomes remains an issue

How can we balance the Eurozone’s need for both financial discipline and risk-sharing?

One way is to make the fiscal rules need to be smarter. A key aspect is to make them more countercyclical. The original rules and the conditionality of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) have forced members in trouble to tighten fiscal policy in the midst of a severe downturn. This pro-cyclicality has been both destructive and divisive. The rules need to more clearly

Smarter and fairer rules would be easier to enforce

and consistently differentiate between current and investment spending, and headline and cyclically-adjusted deficits. Another way is to make the rules more symmetrical; surpluses can be excessive too. ‘Beggar thy neighbour’ policies, such as big and persistent current account surpluses, make it harder for other members to grow and reduce their deficits. Rules that are acknowledged as both smarter and fairer would be easier to enforce.

Is a lack of trust, given current political gridlock, a core problem?

Trust is a big part of the problem. Without it, unity is undermined. Lack of trust then leads people to rely more heavily on rules, but also lose confidence that others will obey them. It also helps to explain why there is little appetite for a ‘transfer union’, involving large-scale fiscal transfers between member states.

Lack of trust also undermines trade and investment

This reflects both a lack of trust: that transfers will be spent wisely, and a lack of solidarity: that the rich are reluctant to support the poor. Over the past decade, in the wake of the financial crisis, the likelihood of transfer union has fallen further. This has fuelled, and been fuelled by rising populism and nationalism. In economic terms, lack of trust also undermines trade and investment.

But it’s not just about trust: there also has to be a common understanding of the problem. There is a clear divide between those who believe the Eurozone’s problems lie more in the supply-side and institutional framework, with those who point to the lack of activism in demand management and burden sharing. Moreover, widening income divides across the Eurozone have made the EU and EMU convenient scapegoats for domestic politicians.

Has the goal of real economic convergence been dropped?

Formally, the EU is still committed to promoting real economic growth and convergence. Last year’s Rome Declaration by EU leaders stated:

“We…pledge to work towards...a Union promoting sustained and sustainable growth, through investment, structural reforms and working towards completing the Economic and Monetary Union; a Union where economies converge."

However, while the formal commitment to convergence remains, in practice, we have the following:

- Politicians have failed to deliver, most critically in the case of Italy. Over the last 18 years, real incomes per head in Italy have fallen by 28% compared with Germany.

- Post-crisis antagonisms and the rise of populism have undermined the strength of this commitment. In this atmosphere, moves to increase convergence will be harder to deliver.

- It is hard to discern a concerted effort to deliver it in the future, whether through domestic economic reforms or larger scale fiscal transfers.

At the Future Europe conference, there was a general consensus that given the current relatively benign economic conditions, now would be a good time to act to speed up efforts to build the Eurozone's resilience to future economic downturns. But as we've seen many times before, politicians' ability to delay addressing fundamental questions about reform to ensure future economic stability is well-known. If they're not very careful, that could be their and the Eurozone's, undoing.

Download

Download article13 July 2018

In case you missed it: The trade war is on This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articles"THINK Outside" is a collection of specially commissioned content from third-party sources, such as economic think-tanks and academic institutions, that ING deems reliable and from non-research departments within ING. ING Bank N.V. ("ING") uses these sources to expand the range of opinions you can find on the THINK website. Some of these sources are not the property of or managed by ING, and therefore ING cannot always guarantee the correctness, completeness, actuality and quality of such sources, nor the availability at any given time of the data and information provided, and ING cannot accept any liability in this respect, insofar as this is permissible pursuant to the applicable laws and regulations.

This publication does not necessarily reflect the ING house view. This publication has been prepared solely for information purposes without regard to any particular user's investment objectives, financial situation, or means. The information in the publication is not an investment recommendation and it is not investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure that this publication is not untrue or misleading when published, but ING does not represent that it is accurate or complete. ING does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication. Unless otherwise stated, any views, forecasts, or estimates are solely those of the author(s), as of the date of the publication and are subject to change without notice.

The distribution of this publication may be restricted by law or regulation in different jurisdictions and persons into whose possession this publication comes should inform themselves about, and observe, such restrictions.

Copyright and database rights protection exists in this report and it may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any person for any purpose without the prior express consent of ING. All rights are reserved.

ING Bank N.V. is authorised by the Dutch Central Bank and supervised by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). ING Bank N.V. is incorporated in the Netherlands (Trade Register no. 33031431 Amsterdam).