Central banks: What’s left in the toolbox?

The resurgence of Covid-19 across Europe and elsewhere is sparking fears of a reversal in the global recovery over the winter. While fiscal policy will continue to do much of the heavy lifting, economic uncertainty is putting renewed pressure on central banks to act. Here's what we expect from them over the coming months

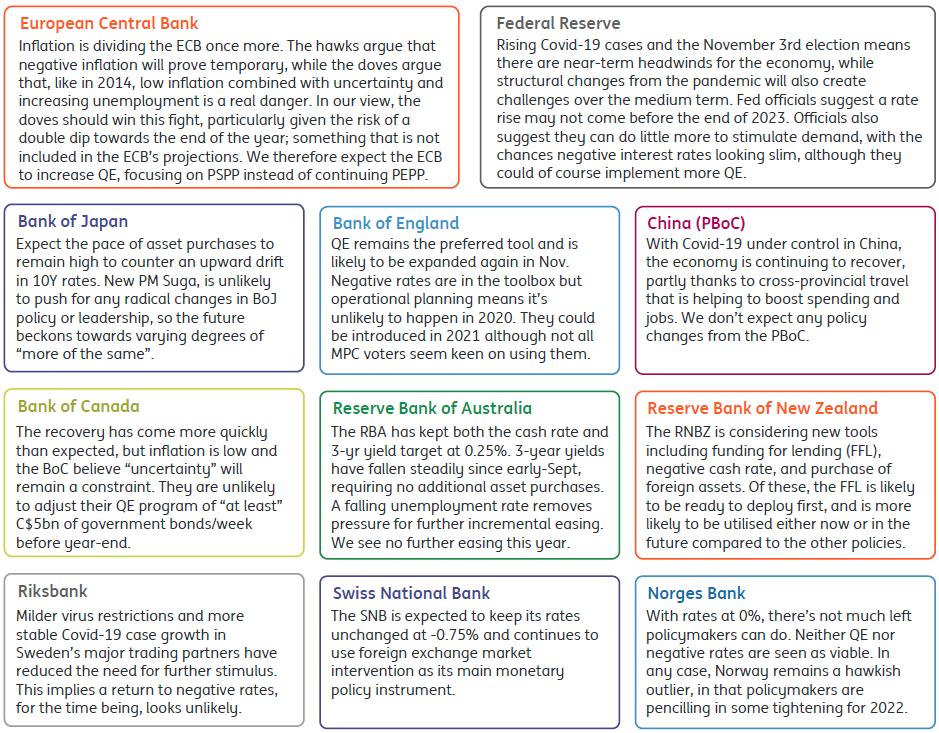

Our view on what central banks will do next

Federal Reserve: We *really* aren't raising rates any time soon...

Officials have been encouraged by the recovery so far, but there is still significant slack in the economy.

Millions of people remain out of work and the Federal Reserve's switch to an “average” 2% inflation target implies interest rates will remain lower for longer than under the previous framework. A pick-up in Covid-19 cases and the 3 November election mean there are near-term headwinds for the economy, while structural changes for many industries resulting from the pandemic will also create challenges over the medium-term.

Fed officials suggest a rate rise may not come before the end of 2023

Fed officials suggest a rate rise may not come before the end of 2023. Officials also suggest they can do little more to stimulate demand with the chances of negative interest rates looking slim, although they could, of course, implement more quantitative easing.

Fiscal policy is the better tool to drive the recovery forward in their minds, but this may not come until after the election.

European Central Bank: The old fight returns

After months of speaking with one voice, the old controversies between hawks and doves have returned to centre stage.

With plummeting inflation rates, increased uncertainty and higher unemployment, the risk of outright deflation has increased. This brings back memories of 2014 and the Draghi era divisions. On the one side, hawks are arguing that negative inflation is only temporary and will reverse in the course of 2021, hence doing nothing is the preferred option. On the other side, doves liken the situation to 2014 and argue that negative inflation, combined with uncertainty and increasing unemployment, is a real danger, hence more action is needed.

We expect the doves to win the fight at the ECB and increase quantitative easing under PSPP instead of continuing the PEPP programme

In our view, the doves should win this fight given that there is a risk of a double-dip recession in the eurozone towards the end of the year; something that is not included in the European Central Bank's base projections. As a result, we expect the ECB to increase quantitative easing, focusing on the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) instead of continuing the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP).

Bank of England: Expect more QE in November, but negative rates on the back burner

Despite the hype about negative rates, the real story of the summer has been Governor Andrew Bailey’s endorsement of quantitative easing as his favoured marginal policy tool - an apparent divergence from the Mark Carney-era. And with Covid-19 cases rising, new containment measures coming in, and the threat of new UK-EU trading terms looming, it’s highly likely that more QE is on the way, most likely in November. An extra £100bn expansion would allow policymakers to continue buying bonds at the current pace into the spring.

We could see the Bank of England using negative interest rates in 2021 if the outlook doesn’t improve

Will this be coupled with negative rates? The Bank of England has signalled they are in the toolbox, but that operational planning will take time, effectively ruling out their usage this year. We could instead see the tool employed in 2021 if the outlook doesn’t improve, although the jury’s out on just how useful policymakers think negative rates would be in practice.

Bank of Japan: More of the same

The last time the Bank of Japan made any meaningful change to its monetary policy was at its 27 April meeting, when it voted to expand purchases of commercial paper and corporate bonds, to expand the scope of eligible collateral it would accept in exchange for funds as part of its special funds supplying operations in response to Covid-19, and to expand purchases of Japanese government bonds to offset the additional issuance expected as a result of government fiscal support (no upper limit to amounts, but yield curve target unchanged at 0%).

The result of this has been a sharp increase in base money from March/April onwards, though the pace of this increase has slowed a little since. JGB yields have remained anchored at roughly 0%, though there has been some minor upwards drift, while short term (3-month Libor) rates have fallen further into negative territory, though remain essentially at their target rate of -0.1%.

Base money growth stepped up in September, presumably to offset the drift upwards in bond yields, and we can expect the pace of asset purchases to remain high until bond yields move lower and approach zero again. New Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, is unlikely to push for any radical changes in BoJ policy or leadership, so the future beckons towards varying degrees of “more of the same”.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

9 October 2020

October Economic Monthly: Winter is coming This bundle contains 12 Articles