UK jobs data suggests ‘on-hold’ Bank of England for time being

For now the official jobs data doesn't look quite as bad as other hiring indicators have signalled. But with Brexit uncertainty already making a comeback and investment set to remain low in 2020, hiring appetite is unlikely to improve significantly any time soon

Will the Bank of England cut interest rates in the first half of 2020? This is the question dividing economists right now. For the moment we think the answer is ‘no’, but the answer will depend heavily on whether the jobs' market deteriorates further.

There are undoubtedly early signs of weakness. Vacancy levels have consistently dropped through 2019. The latest Markit/RECS jobs report points to another fall in permanent placements, while some other recent PMIs have anecdotally indicated that some staff are not being replaced and in some cases, they're being made redundant.

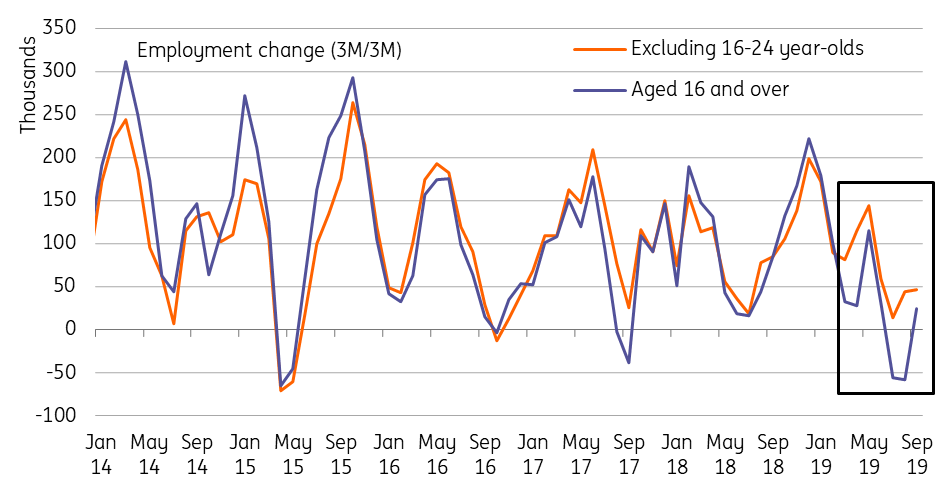

However, all of this is only partially reflected in the latest official figures. Jobs' growth grew by a modest, but positive, 24,000 in the three months to October. As we've seen in the past few readings, a lot of the weakness is concentrated in part-time and 18 to 24 year-old workers. This can be a fairly volatile part of the data and, once removed, the picture has been slightly less negative over recent months, as you can see in the chart below.

UK jobs weakness concentrated in 18 to 24 year-old workers

2020 investment uncertainty will continue to limit hiring appetite

In short, it’s probably too early to make firm conclusions about where the jobs' market is headed. But it’s worth remembering that a lot of the current weakness is driven by persistently low investment, and today’s headlines on the potential non-extension of the Brexit transition period will only add to the uncertain business climate in 2020.

Many experts believe a bare-bones free-trade agreement, completed mostly on the EU’s terms, may just about be possible next year. But there won’t be much time for firms to adjust or for border infrastructure, both physical and technological, to be introduced.

That suggests an extension to the transition in one form or another will be needed, even if that is done via a subsequent implementation phase baked into a basic trade deal next year (as opposed to a straight forward extension of the transition period to 2022).

Until we know for sure, there remains a risk of an abrupt single market exit at the end of next year, and that will continue to put a lid on investment and hiring appetite among firms.

Further hiring weakness poses a risk to recent wage growth strength

Should we see unemployment begin to tick higher, then that would have negative implications for wage growth. Excluding bonuses, pay is growing at a healthy 3.5% annual rate, and this has been a key pillar of the Bank of England's hawkish rationale over recent years.

Admittedly policymakers are already pencilling in a modest fall in wage growth to around 2.5% during 2020. We tend to agree that we're unlikely to see a severe slowdown here, partly because wage gains over recent years have been amplified by other, structural factors. Demographics (high retirement rates relative to new joiners in certain sectors), as well as a noticeable fall in EU immigration, have played a role in driving skill shortages.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download snap