US: Trump & Trade - getting the deal

Trade tensions are high, but President Trump has shown he can be flexible. A deal remains probable, but there are risks of renewed flare-ups

A deal, but June may be too soon

President Trump is in an ebullient mood, talking up the resilience of the US economy and its ability to withstand any negative fallout from US-China trade tensions. He also speaks of the boost to Treasury coffers from the tariffs imposed on Chinese imports. Yet markets aren’t convinced. Bond yields are plumbing new lows, equities have dipped and two Federal Reserve interest rate cuts are now priced in for the next twelve months. More tellingly, the recent economic data appears to be feeling the strain with a massive build-up in inventory levels in recent quarters now being unwound and new orders drying up.

We still think a deal on trade will be done. President Trump continues to offer words of encouragement, talking yesterday of the “good possibility” of a trade deal, one that could include an agreement regarding the “very dangerous” Huawei. Donald Trump has also highlighted his willingness to compromise with the recent decision to de-escalate trade tensions with Mexico, Canada and Turkey. However, we are sceptical that an agreement with China will be signed and sealed at the G20 summit in Osaka in late June as some analysts and clients believe.

The US has a position of strength

While there are signs of a slowdown in business surveys and the manufacturing sector, the labour market is performing well with unemployment at 50-year lows with workers increasingly experiencing higher pay. Consumer confidence is holding up so Donald Trump’s narrative that the economy is doing well and domestic strength can offset some concerns on trade can still hold sway in some quarters.

While many corporates worry about the higher costs, the impact to their supply chains and the uncertainty that trade tensions create, there are plenty that also appreciate and like the fact that he is trying to “level the playing field”. Opening up Chinese markets and doing something to deal with the long complained about appropriation of intellectual property would clearly benefit US firms and many European corporates are delighted too.

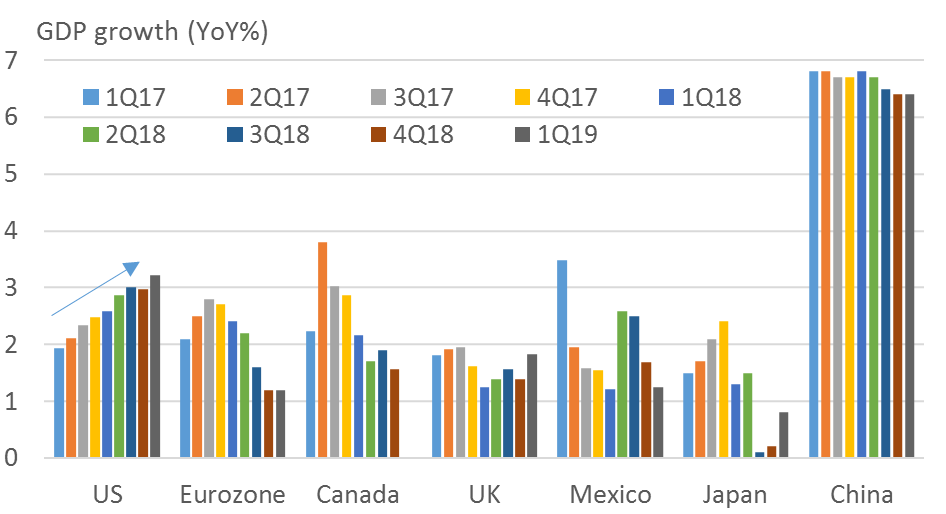

The US is in a good position to extract concessions from China. As the chart below shows the US economy has been moving in the right direction while all other major economies are experiencing slower growth. The US is coming at this from a position of relative strength. President Trump may also feel there isn’t much domestic pressure with the Democratic Presidential candidates increasingly focusing on each other in the battle for their party’s nomination.

US has the momentum as the rest of the world slows

But is time running out?

However, time may be starting to run out to get extra concessions from China. Growth is set to slow in 2Q19 with the Atlanta Fed GDPNow model pointing to growth around the 1.3% annualised rate after the latest disappointing manufacturing and housing numbers. There is obviously the risk that extending the trade conflict beyond June leads US corporates to become more anxious about supply chains and rising input costs (and exports to China) with the uncertainty perhaps dampening appetite to hire new workers and invest. Equity markets are also likely to come under intensifying pressure for similar reasons.

Indeed, the often repeated suggestion that equity markets are a better barometer of his success than opinion polls means that President Trump will need to be wary that pushing too far for too long runs the risk of weakening his re-election campaign. A weakening economy and plunging equity markets is an easy attack line for a Democratic challenger and would be a massive vulnerability in the election campaign.

The China hawks in his camp who are more focused on restraining China's global political ambitions will also be wary as if Trump loses the election they are out of the Administration and will not be able to influence the debate to anywhere near the same extent. As such, I still think President Trump will make compromises to get a deal done. He can then bring the electorate another "win”, but it’s more likely in late 3Q or 4Q rather than June. Such a date would also coincide with efforts getting auto concessions with Japan and Europe, which means nothing can be taken for granted.

Trade tensions will persist

Even if this goes smoothly and tensions dissipate, this won't be the end of the trade conflict. If President Trump wins re-election, but the Democrats retain control of the House of Representatives it means his domestic legislative agenda will be constrained. It will be immensely challenging to get additional tax or healthcare changes through given steadfast Democratic opposition. He may get something on infrastructure, but it will likely be limited in scope and scale. I would expect a flaring up of trade tensions once again in 2021-2022 as he seeks more from China and probably the EU. He will want something to cement his legacy as President.

Even if a Democrat were to win we are unlikely to see a return to the internationalist approach under Barack Obama. Centrist Democrats are being forced to talk a tougher line on trade with China given Trump warning a Democrat president will be "weak" regarding the situation - Joe Biden has already been heavily criticised. The protectionist situation could even be intensified if we get a populist Democrat who is keen to protect blue collar jobs.

The implication of this is that things "won't go back to the way they once were" and corporates will need to be wary about relying on global supply chains. US-China tensions will persist and we could see more facilities moved to the likes of Vietnam, Taiwan and Malaysia to try and circumvent the issue. We may also see some companies shrinking their international supply chains and on-shoring operations back to the US. This may reinforce the recent trend of global trade volumes underperforming global growth.

Download

Download opinion28 May 2019

What’s happening in Australia and around the world? This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articles

James Knightley

James Knightley is the Chief International Economist in New York. He joined the firm in 1998 in London and has been covering G7 and Western European economies. He studied economics at Durham University, UK.

James Knightley

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more