Beyond Mobile Banking – A List of 6 Ways to the Future

The outlook for mobile banking has never been brighter. Its adoption has been much faster than the internet banking that preceded it. It’s so irresistibly convenient. And there’s far more to come.

Financial markets are in turmoil and many economists are miserable about growth prospects. But tell this to the fintech world. The outlook for mobile banking has never been brighter. Its adoption has been much faster than the internet banking that preceded it. It’s so irresistibly convenient. And there’s far more to come. Here’s six ways it could develop:

1. Advice

Right now mobile banking is very transactional. Most mobile banking apps allow you to pay bills, make payments, transfer money, check your balances or find a branch or an ATM. Some offer fancier analysis of your finances or more product information, but it’s largely functional, generic and task orientated.

This is all set to change. Financial innovators are working on turning your mobile phones and tablets into virtual digital advisors. Mobile banking will move beyond the transactional, product-pushing approach to one that is radically customer-centric, pro-active and goal-oriented, aimed at helping users make smarter decisions.

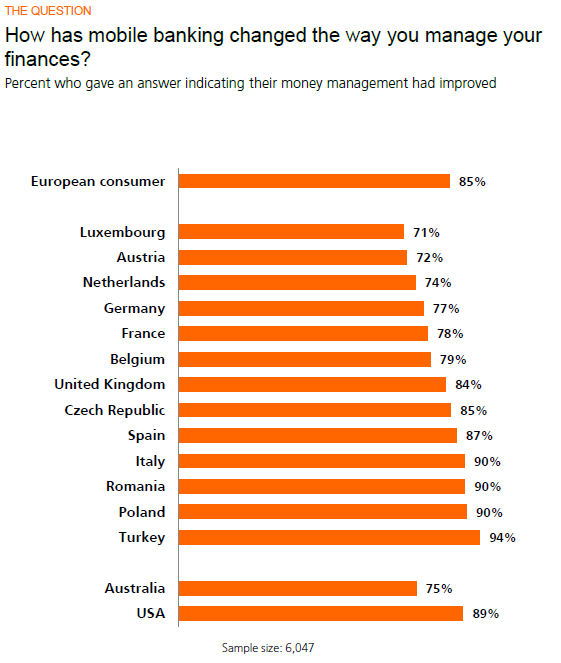

ING’s International Surveys of consumers show that they have a strong appetite for this. In a recent survey, 85% of European consumers said that their money management had improved because of mobile banking.

How has mobile banking changed the way you manage your finances?

Percent who gave an answer indicating their money management had improved

To build on this demand providers will need to develop a much deeper understanding of their users, beyond the merely financial. What are they trying to achieve in life? Their account balance and past transactions will only provide a few clues.

So providers will have to provide richer interactions with their clients to learn more about their motivations, and make intelligent inferences from the behaviour of people with similar profiles. They will also have to draw upon third-party data sources to build more complete pictures of individuals and their families, friends and social networks.

The beginnings of this trend can be seen in the market for investment products, with the launch of ‘robo-advice’ services. These offer portfolio-management tools, with automated advice based on data users provide, such as online risk-appetite evaluations. For example, younger, risk-tolerant investors will typically be advised to put a bigger proportion of their portfolios into equities, for example.

For providers and users alike, the mutual cost savings on relatively large investment transactions make them an attractive place for robo-advice to start. But there is scope for the trend to extend into the full range of financial decisions, even to mundane daily shopping transactions. Ever more efficient systems are commoditising the payments business, so the search is on, by banks and fintechs alike, for added value services around the payments business.

Here the big prize for banks is to do more than merely executing the payment. What if they could use their knowledge and data to make help you make a better choice?

Big transactions, like buying homes or cars, are months, if not years, in the planning. Right now, banks are generally only involved at, or near, the moment of payment. But with their transactions data and expertise, banks could step in to help users search, building on the experiences of millions of other customers.

Even with smaller transactions banks could play a more active role in providing tips and tools to help, given their role at the heart of the payments system. Indeed, they could embed themselves in the whole transaction journey of searching, buying and, in some cases, use (think of feedback and reviews on purchases). As a result, they would be involved not just in the ‘how’ to buy, but the ‘why’ (“do I need this?”), ‘what’ (“which product should I buy?”), ‘when’ (“should I wait?”) and ‘where’ (“who’s offering the best deal?”). The obvious question is: would users want this? The short answer is yes, so long as they found it useful. That usefulness will be enhanced by the other emerging fintech trends.

2. Access

The banks’ mobile apps typically focus only their payments and savings accounts. Most people have other financial products and have money, savings, loans or investments with other banks or providers. The result is that most bank apps only give a partial picture of individuals’ finances, which presents an obvious problem for their aspirations to deliver digital advice.

So the next big trend is ‘aggregation’, combining people’s financial data from multiple sources to build up and analyse a holistic picture of their finances. You need to know your total income and spending, the value of your loans, savings, investments and assets before you can make reliable plans and budgets. Some providers have started tackling this challenge, which faces formidable legal and IT hurdles, but the enormous potential value to users suggests that it will ultimately be met.

In effect, banks will have to rethink their business models, moving beyond the aspiration of being the single multi-product provider to their customers to offering value-added platforms for customers to access and manage their finances, whatever the source.

But why stop at financial products? Having built a complete financial platform for their clients, banks could also provide access to the purchase of other products and services. Many banks are worried that the likes of Google and Amazon might move into financial services and “eat their lunch”. But by providing access to multiple online marketplaces, big banks, who after all have huge customer bases, could take the game to the tech giants.

3. Affective

This brings us to a third direction for mobile banking development. While the adoption rate of mobile banking has been near-exponential, it’s not an activity that takes up more than a few minutes of the three-hours-plus a day that many mobile users are spending on their devices. It’s functional, even boring. But it doesn’t have to be.

Indeed, if banks aspire to become omni-present trusted advisors, they are going to have to build a much deeper emotional connection with their clients. Financial transactions may not be fun (although people do get a buzz from bagging a bargain), but the spending goals that lie behind them are often emotionally engaging. Think of the excitement around buying an exotic holiday or a present for a friend

Financial decisions are woven into people’s lives, so people’s feelings and emotions need to be taken into account. The new field of ‘affective computing’ is already making progress in developing sensors to do so. Combined with the insights of behavioural economics, which has discovered a wide range of psychological biases that deflect us from the coldly rational calculations of traditional economic theory, this could lead to much smarter devices. By learning from your moods and behaviour and that of those like you, they could help you make decisions that are not just more cost effective, but more satisfying; ones that not just avoid mistakes, but also lead to success.

4. Associative

Talking of satisfaction, people derive happiness largely from interactions with others. We’re social animals. Most household financial decisions are driven by the needs, interests and reactions of other members of the household or family. We care about the reactions of our friends, neighbours, colleagues and peers. Yet mobile banking apps are still locked in the private world of you and the bank. So there’s huge scope to make mobile banking more social.

This is not to say that people are keen to share their financial secrets with one another. They’re not. However, facilitating intra-family and intra-household goal setting, budgeting and transfers would be a good place to start. In the new world of virtual digital advice, people may be happy to share their wish lists, tips and tricks, reviews and experiences with others. After all, people trust their families and friends more than companies.

Preserving privacy and security will be a precondition here; this will also depend on users opting in only to the features that they want and personal data being protected or anonymised by aggregation.

Now you might be thinking, aren’t existing social networks like Facebook better placed to do this? Perhaps. But the banks, for now, do have some advantages, . They have millions of customers, even if they have barely begun to connect them into on-line communities. They have financial data, on incomes as well as transactions, that the social networks and tech giants might die for. They also have the lead in expertise in cybersecurity, credit evaluation, and financial planning.

Think of the possibilities. On savings, for example, most people have particular goals in mind, such as buying a car. Within their client bases, banks have ready-made communities of potential car buyers, who could share thoughts about which cars to buy, where to buy them, how to maintain and insure them.

Or think of the trend towards crowdfunding. Banks could facilitate the development of platforms for all forms of peer-to-peer finance. Existing joint ventures with P2P platforms hint at a future of more collaborative finance.

5. Agile

A fifth direction for mobile banking is to become more forward-looking and dynamic. People appreciate the new 24/7 convenience of mobile banking, but it’s all a bit static and backward looking.

By harnessing ‘Big Data’ about users and applying the tools of predictive analytics, banks are already starting to provide more sophisticated alerts about their clients’ finances. Looking at their typical spending, for example, they can be warned that their account might be about to slip into overdraft.

Eventually, these personalised micro-economic forecasts might stretch into the longer term, such as indications of future utility bills or the ranges of potential savings returns. Indeed, such personalised forecasting is essential if mobile banking morphs into financial advice, because all borrowing, saving and investments require a view on the future.

The transformation towards holistic advice will also require even higher frequency contact with users. Although mobile banking has already multiplied the number of contact moments between clients and their banks this has much further to go. Rather than being event-driven, or merely reporting to or alerting users, finance will become more interactive, immersive and engaging.

In the background, the virtual adviser will have to remain ‘always on’, scanning for opportunities and threats to its users. In the process, users, like their devices, will learn as they go along about how to make smarter decisions.

6. Ambient

The notion of an adviser ‘always on’ suggests that the ultimate direction of mobile banking will be to free itself from dependence on mobile devices such as the app-driven smartphones and tablets that we are familiar with today. The development of cloud-based computing, artificial intelligence and the ubiquitous sensors of “the internet of things” open up the prospect of ‘ambient computing’. In the coming decades, we might migrate to an electronic environment that recognises our presence, senses our situation, anticipates our needs and responds to our commands. Let’s just hope that the ambient financial advisor figures out a way of handling financial market turmoil…

Download

Download opinion"THINK Outside" is a collection of specially commissioned content from third-party sources, such as economic think-tanks and academic institutions, that ING deems reliable and from non-research departments within ING. ING Bank N.V. ("ING") uses these sources to expand the range of opinions you can find on the THINK website. Some of these sources are not the property of or managed by ING, and therefore ING cannot always guarantee the correctness, completeness, actuality and quality of such sources, nor the availability at any given time of the data and information provided, and ING cannot accept any liability in this respect, insofar as this is permissible pursuant to the applicable laws and regulations.

This publication does not necessarily reflect the ING house view. This publication has been prepared solely for information purposes without regard to any particular user's investment objectives, financial situation, or means. The information in the publication is not an investment recommendation and it is not investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure that this publication is not untrue or misleading when published, but ING does not represent that it is accurate or complete. ING does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication. Unless otherwise stated, any views, forecasts, or estimates are solely those of the author(s), as of the date of the publication and are subject to change without notice.

The distribution of this publication may be restricted by law or regulation in different jurisdictions and persons into whose possession this publication comes should inform themselves about, and observe, such restrictions.

Copyright and database rights protection exists in this report and it may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any person for any purpose without the prior express consent of ING. All rights are reserved.

ING Bank N.V. is authorised by the Dutch Central Bank and supervised by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). ING Bank N.V. is incorporated in the Netherlands (Trade Register no. 33031431 Amsterdam).