Why the Bank of England is likely to steer away from negative rates

While the short-term outlook is incredibly bleak, the prospects for the recovery have improved since the Bank of England's last meeting in November. We therefore think the Bank will opt against a move to negative rates in February, though never say never - the downside risks to the economy clearly outnumber the upside

When will life get back to normal in the UK? While the answer to that question remains highly uncertain, reports in the British press this weekend contained some helpful clues.

We now know that the government’s vaccination programme has hit 200,000 people per day, and with more centres due to open in coming days, two million weekly doses could become reality within the next couple of weeks. Whether or not that is sufficient to meet the government’s target to vaccinate all over-70s by mid-February is hard to say, but what it does suggest is that the first dose could feasibly be given to the vast majority of people in priority groups (over 50) by Easter - assuming supply comes as hoped.

That said, reopening the economy is clearly going to be a gradual process. By mid-February, the hope is that the mortality rate will have begun to decline - potentially quite rapidly. Analysis by the Covid-19 Actuaries Response Group implies that vaccinating over 80s and healthcare workers could help reduce the rate of mortality by almost 70% (assuming the vaccine is 100% effective).

Unfortunately however, reducing the pressure on healthcare services is likely to take longer. Two-thirds of UK ICU admissions for Covid-19 have been below the age of 70, which implies that all over-50s will need to be vaccinated to achieve a significant decrease in healthcare pressure.

Rough timeline shows 2m weekly doses could help partially vaccinate over 50s by Easter

Two-thirds of Covid-19 critical care patients are below age 70

New lockdown set to deliver 3% hit to first quarter GDP

For the economy, this almost certainly means that the majority of services that are closed will remain so for most - if not all - of the first quarter. The heightened transmissibility of the current strain means that a return to softer regional measures is unlikely to be feasible before healthcare pressure has reduced. The Sunday Times reported that the latest government thinking is that there could be some initial reopening late into March (shops?), followed by hospitality in early May.

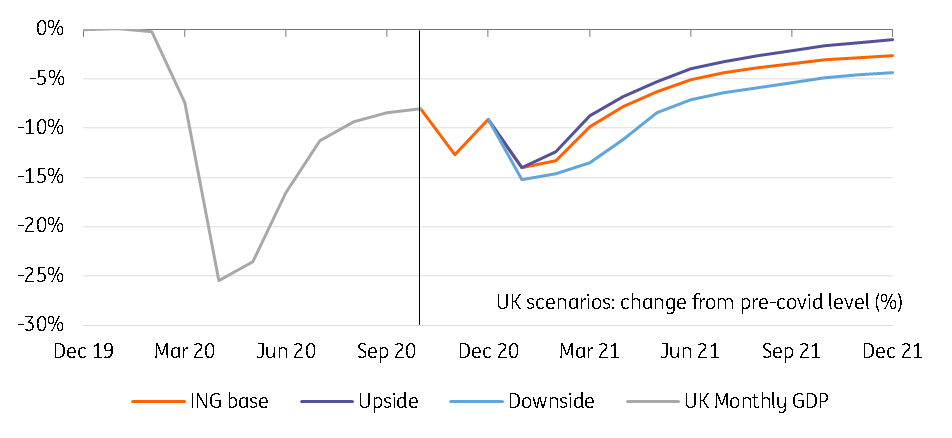

The result is likely to be a 3% fall in first quarter GDP, which would take the size of the economy to some 15% below pre-virus levels - compared to 25% at the peak. Businesses are better adapted to the new rules than back in March 2020, while a greater range of sectors are still able to operate. The contraction is however likely to be larger than during the November restrictions. Unlike then, schools are closed and that both directly feeds into the GDP figures via lower attendance, but also puts pressure on other sectors given increased childcare needs. It also goes without saying that businesses are suffering from greater staff absence due to sickness/self-isolation compared to November.

Three scenarios for 2021 UK GDP

How we're assuming different industries will recover

Bank of England likely to steer clear of negative rates this winter

Having said all of that, we still think the Bank of England will opt against implementing negative rates this quarter.

At the February meeting, the Bank is expected to unveil the findings of its survey of commercial banks which sought views on how sub-zero rates would impact them. We’ve long felt the impact on bank profitability is unlikely to be the factor that steers the MPC away from using negative rates. But there is clearly still an active debate on whether the policy would carry many benefits. While some external MPC members, including Silvana Tenreyro, have indicated their support, other members - notably Chief Economist Andy Haldane - have thus far been less enthusiastic.

We don’t expect the committee to completely close the door on negative rates

And despite the near-term hit to the economy, the more important story from a monetary policy perspective is that the broader 2021 story is better than it looked in November. Back then we felt that the Bank’s forecasts were a bit too optimistic - and arguably the assumption that the economy would return to pre-virus levels around the start of 2022 still looks a little rapid. But the arrival of vaccines, as well as a Brexit deal, has reduced some of the downside risks that were present back at that meeting.

Assuming the most burdensome social distancing closures are phased out through the spring, we think the second quarter could see growth in the region of 6-7%, followed by a further 2-3% in the third quarter.

We therefore don’t expect much action from the BoE in February, though we wouldn’t rule out an acceleration in the pace of bond purchases, or tweaks to make the Term-Funding scheme (designed to incentivise lending to SMEs) more favourable. Admittedly, we don’t expect the committee to completely close the door on negative rates - and they may go as far as formally saying the ‘lower bound’ has shifted below zero.

That’s partly because the 2021 outlook still remains incredibly uncertain - and arguably the downside risks outnumber the upside. Below are some headline risks to the outlook.

Potential risks to the outlook

- The short-term damage becomes greater. The government could tighten restrictions further, and for the economy the biggest hit would come if construction and/or manufacturing were constrained. Our downside scenario assumes a more severe hit to these sectors (though not on the scale of last spring), which could increase the decline in first quarter GDP to 5%+.

- The vaccine rollout takes longer. The obvious risk here is that of a Covid-19 variant threatening the effectiveness of existing vaccines. The uncertainty here is a) whether such mutations reduce effectiveness enough to require the current strictness of social distancing rules to be maintained and b) how long it would take to roll out a tweaked vaccine. The FT has reported that it could take several months to manufacture a tweaked version of the Oxford/Astrazenica vaccine, which currently makes up the bulk of the UK’s supply. Ultimately, this will be an ongoing challenge over coming years, even if things go as hoped through the spring.

- The government is more risk-averse on the reopening. While the hope is that hospitalisations are reduced significantly by the spring, circulation may well remain high in the less vulnerable groups. This means the health impact will continue to be felt (‘long Covid’, for example), but higher circulation also presumably means a greater risk of significant mutation. It's possible then that the government takes the reopening phase very slowly until all groups have been vaccinated, which is unlikely before the autumn.

- The post-Covid boom is larger than anticipated. It’s not all bad - and one clear upside risk is that consumers vigorously deploy the pool of savings many have built through 2020 when they are able to spend money. To an extent this is likely whatever happens - particularly for travel and other things that have been shut. The key question is whether this creates strong enough momentum to rapidly reduce unemployment - which is likely to move higher in the spring depending on how/when the government removes its unprecedented wage support. Our base case assumes that, while spending will see a marked recovery through 2020, this deterioration in consumer fundamentals will prevent the economy returning to its pre-virus level until late 2022 or beyond.

(Brexit will clearly also weigh on the outlook - we'll return to this in a separate article in coming days)

Download

Download articleThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more