US: Are we heading to recession?

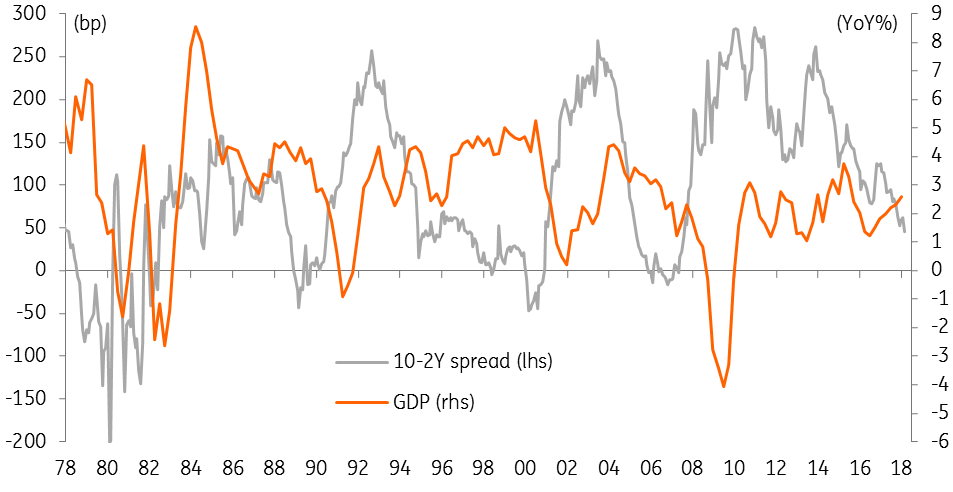

The US yield curve keeps getting flatter with growing concern it could turn negative. Such a development preceeded all nine recessions since 1955. How worried should we be?

Yield curves and the economic cycle

The US yield curve is currently the flattest it has been for a decade. With the Fed looking set to hike rates another three times this year a growing number of voices are warning we could soon see the yield curve actually invert, meaning it is cheaper for the government to borrow over ten years that it is over 2 years. This is a huge story. When the yield curve has inverted previously it’s been an early warning signal of impending doom - the US has typically fallen into recession within 2 years.

The US yield curve and GDP growth

That said, it is important to remember that this is a guide, not a rule. In 1998 when we saw a very temporary shallow inversion following the Asia/Russia/LTCM crises, a swift Fed response meant the economy powered on and the yield curve quickly normalised with a positive slope.

Nonetheless, even in a relatively benign situation such as then, an inverted yield curve would signal bond market nervousness that could trigger a broader switch towards safe-havens and provide some respite for the beleaguered dollar.

Why invert?

Yield curves typically steepen ahead of a central bank tightening cycle as the market anticipates higher interest rates and then flatten as the central bank actually raises short-term rates. This is the process we are seeing right now. But if it continues and the curve inverts, history would suggests there are two main scenarios that we face:

- The concerning one: The market believes the Federal Reserve is making a policy mistake by raising short-term interest rates too aggressively. This prompts an economic downturn that requires corrective action later on and is bad news for risk assets.

- The more benign one (ie, 1998): The economy and inflation pressures aren’t as strong as the Fed believes and we will see those anticipated Fed rate hikes priced out, lowering shorter dated yields, which prompts a re-steepening the yield curve. This is less damaging for risk assets.

The Fed divided

Over the past couple of days we have heard several Fed officials offering their perspective. As you would expect, there are a range of views.

St. Louis Fed President James Bullard (a noted dove) suggests we could see a negative yield curve within the next six months if the Fed pushes ahead too aggressively with rate hikes. He advocates a “wait and see” approach to monetary policy, believing that there is little inflation threat in the economy. It’s important to remember he doesn’t get to vote on Fed decisions this year.

San Francisco Fed President (from June NY Fed president) John Williams admits that an inverted yield curve has in the past been a “powerful signal of recessions”, but he doesn’t “see the signs yet of an inverted yield curve”. He believes that there is more of an inflation threat than Bullard, which will mean longer dated bond yields will move higher, but that the curve will continue to flatten – “it’s totally normal” in his view.

Fed Governor Quarles agreed yesterday, saying “I’m not viewing the current flattening of the yield curve as a particular signal towards pending recession”. Like Williams, he believes the longer end of the bond market is lagging behind and will respond.

Inversion avoided... for now

We have more sympathy with the views of Williams and Quarles than we do for Bullard’s at this stage. We remain upbeat on the US economic prospects. Domestic demand is strong, supported by strong jobs market, rising house prices and an expansionary fiscal policy driven primarily by significant tax cuts. At the same time the US dollar’s depreciation means that exporters are in a competitive position to benefit from the upturn in the global economy. If in addition President Trump can make progress on infrastructure investment this could help extend the US economic cycle.

Meanwhile, consumer price inflation is broadly in line with the Fed’s 2% target. Given the tight labour market, we find it quite easy to envisage wage growth rising above 3.5% YoY later this year. With energy prices and import prices picking up again there is the possibility headline CPI rises towards 3%.

In this environment of robust growth and rising inflation we forecast the Fed raising rates three more times this year with a further two, possibly three likely for 2019. This would take the Fed funds rate up to around 3%.

We also see upward pressure on longer dated yields. For reasons already stated, we think that the bond market is under-pricing the threat of higher US inflation - consensus estimates suggest inflation will be benignly rise fractionally above 2% before settling at that level for the next few years.

Then there is the Federal deficit, which is set to hit $1 trillion dollars next year or 5% of GDP. This requires a massive increase in government debt issuance, much of which is likely to be in the form of longer dated treasuries, at a time when the Federal Reserve is running down its vast balance sheet. This change in the supply/demand mix could provide upside impetus for longer dated bond yields.

As such we see 10Y yields rising towards 3.5% and a Fed funds terminal rate of around 3.25-3.50%. But the Fed does not get anywhere near that this year. Hence the probability of inversion is low for 2018.

But we acknowledge the risks

The US economy is undoubtedly late cycle – we are in the midst of the second longest US economic expansion since the end of World War Two and debt levels are clearly on the rise. Consequently the response to higher interest rates is somewhat uncertain, but this is one of the reasons why the Fed continues to emphasise its “gradual” approach to policy tightening. Add in the fear of an escalation of protectionist policies that could de-rail the positive global and US growth story and we acknowledge there is some justification for bond market nervousness that could lead to an inversion.

That said, it is important to remember that a negative yield curve doesn’t mean recession is inevitable. Obviously, the US will eventually experience recession again, but for the next couple of years we remain upbeat with the global growths story while a competitive dollar and ongoing fiscal stimulus and infrastructure spending can help prolong the economic cycle.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

19 April 2018

US: A milestone, a short squeeze and a Q1 conundrum This bundle contains 5 Articles