Unfair trade: Does President Trump have a point?

According to President Trump, there isn't a level playing field between the US and many of its trading partners. For example, China doesn't protect the intellectual property of foreign firms and on average levies higher import tariffs. Does he have a point?

Investment restrictions and the theft of intellectual property

“A historic move against economic aggression”, is what the White House called it when announcing a 25% tariff targeting US$50-60bn of imports from China. This follows frequent complaints about the abuse of intellectual property rights by China and the restrictions on foreign investments in China. According to President Trump, the US trade deficit is the result of unfair trade policies by other countries.He refers to unequal tariffs, like those in the automobile industry, complaints about unequal restrictions for foreign investments in China and the abuse of intellectual property.

The new US tariffs on imports from China have been announced, citing the section 301[1] investigation into alleged intellectual property theft by China. Does Trump have a point here? According to the European IPR SME help desk, there are indications for this. IFR SME puts forward that plant inspections in China, which are required for certifying products for sale on the Chinese market, are not uncommonly carried out by inspectors from competing for Chinese firms.

[1] Section 301 of the 1974 Trade Act allows the President to retaliate against countries if they violate international trade agreements, act unjustifiable, and, or, burden US commerce.

Chinese companies are often accused of counterfeiting brand names, patents, and the theft of technology. Market access is often restricted, and technology transfers are sometimes demanded to gain access to the Chinese market.

The Chinese government has selected specific sectors in which technology transfers and localisation strategies are to be implemented. For those sectors, including car manufacturing, China does not allow full foreign ownership. This means that often foreign companies can only enter the Chinese markets through a joint venture.

Chinese tariffs are significantly higher than US tariffs

Applied WTO goods tariffs

Simple averages: data from 2016 computed by the WTO. Trade weighted averages are computed aggregated on a 6 digit scale using 2017 data.

When comparing the WTO[1] applied tariff profiles of the US with China and the EU, Chinese tariffs immediately catch the eye (Figure 1). As a simple average, China’s import tariffs are 9.9% while those of the US are 3.5%. This does not only concern agricultural tariffs, but also tariffs on the import of manufacturing such as transport equipment, electrical machinery, and clothing (Figure 2). The EU levies higher tariffs than the US on most of its imports as well, albeit those differences are relatively small (less than 2 percentage points for most product groups, see Figure 2). European import tariffs on agricultural products are significantly higher than those levied by the US.

[1] It is important to keep in mind that these tariffs are not specifically levied on imports originating from the United States. These tariffs are levied on imports from all countries. Therefore access to the Chinese market is just as restricted for European firms as for US firms.

Tariff differences, the US vs China and EU

Difference in simple averages measured in percentage points, positive number implies that US are lower.

The higher tariffs charged by the EU and China doesn't necessarily mean that the US is treated unfairly. Non-tariff barriers are as important as the level of trade restrictions.

Research from Ecorys shows that while the EU levies higher tariffs on goods, the US is more restrictive than the EU when it comes to non-tariff barriers as (Figure 3). The US non-tariff barriers are about the same for goods but significantly higher for services. So higher European tariffs could well be offset by lower non-tariff barriers in the EU given the fact that non-tariff barriers are increasingly important nowadays. According to Ecorys[1], non-tariff barriers are in many cases even more important than tariffs nowadays. This implies that the EU-US playing field is quite level. So, contrary to China, Trump does not have a point when it comes to Europe.

[1] Berden, K.G., J. Francois, S. Tamminen, M. Thelle and P. Wymenga (2009), “Non-Tariff Measures in EU-US Trade and Investment – An Economic Analysis”, Ecorys report prepared for the European Commission, Reference OJ 2007/S180-219493

Non-tariff measures between the US and EU (a simple average)

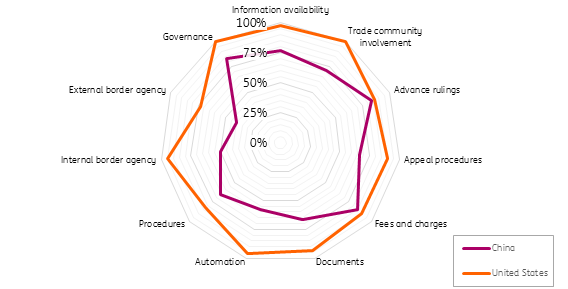

To our knowledge, an overview of the level of non-tariff barriers in China compared to those in the US is not available. However, trade facilitation is related to non-tariff barriers. When looking at trade facilitation, China is more restrictive than the US as the figure below shows. Add this to the higher levels of tariffs in China; President Trump does seem to have a point when complaining about Chinese trade policy.

Trade facilitation between the US and China

Does the difference in protectionism matter?

Although President Trump does have a point when complaining about China's protectionism level, it doesn’t mean that bilateral trade deficits are always due to differences in protection of domestic industries.

Firstly, bilateral trades the result of specialisation differences due to comparative advantages, for example, the availability of cheap labour in one country and a high level of technology in another country. Taking advantage of specialisation differences is nothing else than rational economic thinking. Even if the level of all tariffs and non-tariff barriers were the same in all countries, bilateral deficits and surpluses would occur due to differences in industry competitiveness caused by different specialisation processes.

The overall trade deficit of the US is first of all a reflection of US over-consumption, in other words, a lack of national savings. National production in the US cannot keep up with the consumption and investments of the private and public sector. So, even though improving the competitiveness of the US can improve bilateral trade balances, the overall trade deficit of the US will only diminish if the American private and/ or public sector increase their savings.

Moreover, trying to equalise bilateral trade balances by raising American import tariffs can increase domestic production, but this has negative side effects. Not only does it drive up consumer price inflation, but it also drives up the cost for exporters. Many US exports contain imported components such as iron or steel, therefore, raising tariffs on these goods harms US exports. The damage will increase further if countries hit by higher US tariffs would retaliate.

As far as creating a level playing field improves bilateral trade balances for the US, it can best be done by trying to persuade trade partners to lower their import tariffs because this leads to lower prices. Thus it increases the purchasing power in the destination countries for US exports and thereby increases demand.

In conclusion

Chinese import tariffs are much higher than US import tariffs and in terms of trade facilitation, China is less open than the US, which is why we feel that President Trump does have a point when complaining about Chinese tariffs. He also has a point about China being notoriously weak in protecting intellectual property.

However, raising US import tariffs to address these concerns may not be the best policy response, because it runs the risk of retaliation by China which would be the start of a trade war that would be damaging for both countries.

On net, protectionist measures by the US and the EU are roughly in balance. So raising US tariffs on imports from the EU cannot be justified by referring to higher tariffs in sectors like the automobile industry or agriculture.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

4 April 2018

In Case You Missed it: Trump’s trade fight This bundle contains 6 Articles