New Money III: Why the crypto debate is far from over

One clear example of “New Money” is cryptocurrency, which fits into the broader category of crypto-assets. The market suffered huge losses last year casting some doubt on the future of alternative currency regimes. But we offer two reasons why the crypto debate is not going away and explain how it fits within the current economic and monetary discussion

The debate around crypto is far from over

There is no doubt that 2018 was a reality check for crypto enthusiasts. Q4 2018 saw a strong contraction in the cryptocurrency market, which led to a 45% loss of almost $100 billion in market capitalisation. This is hardly surprising: the value of peer-to-peer cryptocurrencies has no clear economic or legal basis. As we argued elsewhere, they do not satisfy the three basic functions of money: store of value, means of exchange and unit of account. Therefore, the steep increase in the exchange rate in the early stage of their adoption was simply unsustainable. However, although the hype around Bitcoin is rapidly fading away, the debate around crypto remains quite active and far from over, so here are few reasons why you do need to keep watching this space.

The rules of the game: “in algorithm we trust”?

Crypto supporters often argue that with blockchain technology and cryptocurrencies it is possible to build a financial eco-system with decentralised governance. Yet there are several issues with this idea. Firstly, before you can trust an algorithm you need to trust its coder. Ultimately, the “money” business is a “trust” business. Some people say: trust the code, instead of the intermediary. But most people cannot interpret the code. So people need to hire someone to vet the code for them. But wait, that's just an intermediary. Only this time, it's an auditor.

Secondly, we think that a centralised governance is more likely to succeed given the strong economies of scale behind the proliferation of digital assets. The economic forces driving digital assets are no different than a platform-dominance game: the value increases (for all customers) as more clients join. For example, having one phone in a network is useless, but having 10 phones is much more useful. By extension, the value of the network increases as more people join the phone network.

An area where algorithms could potentially assist is in the conduct of a monetary policy rule (e.g. Taylor rule). However, it is hard to imagine monetary policy on "autopilot" without some form of public accountability. What would happen when things go wrong and who would bear the ultimate responsibility? But more importantly, monetary policy is often discretionary rather than rules-driven. There is a difference between decentralised software, and a market without public intervention. Maybe technology could help to address the first issue, but market failures do exist irrespective of technology. Therefore, don’t expect public intervention to disappear following a technological innovation – not even a breakthrough one.

Can cryptocurrencies escape the “impossible trilemma” curse?

So, what is stopping governments from adopting cryptocurrencies? There are two main issues, one relates to technology, the other one to international finance and politics.

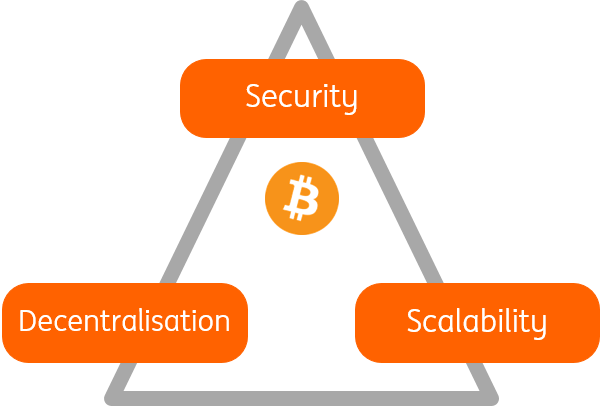

The first issue is the Scalability Trilemma, which describes the impossibility, at least with current technology, to have scalable, secure and fully decentralised cryptocurrencies all at the same time (Fig.1). In other words, you can pick and choose two out of three options, never all of them together. Bitcoin, for example, prioritised security and decentralisation over scalability. Conversely, if you want a decentralised and scalable cryptocurrency, you have to make concessions on security. You can’t have them all.

Fig. 1 - The Scalability Trilemma

The second issue relates to another popular Impossible Trinity, which states that a country cannot achieve free capital mobility, monetary policy autonomy and a stable exchange rate all at the same time (Fig. 2). As an example, if a small open economy decides to peg its exchange rate to that of a more developed country, then according to the trilemma, the smaller country is confronted with a choice: either it preserves the freedom to conduct monetary policy in the presence of capital controls, or alternatively it binds its monetary policy to that of the other central bank preserving free capital movements. If two countries had, for example, two different policy rates in the presence of free capital mobility, strong capital flows would add further pressure to break the parity.

Fig. 2 - The Policy Trilemma

So, how do cryptocurrencies fit within the latter? On the one hand, governments can shut down cryptocurrencies at any time. However, the main point here is that even if governments were to adopt a cryptocurrency as their legal tender, the Impossible Trinity would bind governments to stick to either option A or B in the chart above, effectively diminishing their “policy menu”.

These are two important reasons why we don’t expect a wide adoption of cryptocurrencies in the new future. In our view it is more likely to see progress on central bank-issued digital currency, which is the topic of a separate New Money article. Moreover, the blockchain technology underlying cryptocurrency remains promising. One area where we see a lot of potential is that of securities trading on a blockchain platform: security tokens, which we will also address in a separate New Money article.

Download

Download article21 June 2019

New Money: A new chapter for central banks and capital markets This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articles"THINK Outside" is a collection of specially commissioned content from third-party sources, such as economic think-tanks and academic institutions, that ING deems reliable and from non-research departments within ING. ING Bank N.V. ("ING") uses these sources to expand the range of opinions you can find on the THINK website. Some of these sources are not the property of or managed by ING, and therefore ING cannot always guarantee the correctness, completeness, actuality and quality of such sources, nor the availability at any given time of the data and information provided, and ING cannot accept any liability in this respect, insofar as this is permissible pursuant to the applicable laws and regulations.

This publication does not necessarily reflect the ING house view. This publication has been prepared solely for information purposes without regard to any particular user's investment objectives, financial situation, or means. The information in the publication is not an investment recommendation and it is not investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure that this publication is not untrue or misleading when published, but ING does not represent that it is accurate or complete. ING does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication. Unless otherwise stated, any views, forecasts, or estimates are solely those of the author(s), as of the date of the publication and are subject to change without notice.

The distribution of this publication may be restricted by law or regulation in different jurisdictions and persons into whose possession this publication comes should inform themselves about, and observe, such restrictions.

Copyright and database rights protection exists in this report and it may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any person for any purpose without the prior express consent of ING. All rights are reserved.

ING Bank N.V. is authorised by the Dutch Central Bank and supervised by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). ING Bank N.V. is incorporated in the Netherlands (Trade Register no. 33031431 Amsterdam).