Trade Wars: Episode 1 - The Presidential Menace

Four scenarios for how trade wars could unfold and how costly a global trade war would be for major economies - as well as the implications for the US dollar and global risk sentiment

Key Messages

- For global market dynamics to transition from what we see as currently being a Cold Trade Conflict to a real Global Trade War, we need to see one of two things: (1) a broadening of current US protectionist measures to other countries/sectors or (2) the US administration reacting to any initial retaliatory tariffs from Beijing.

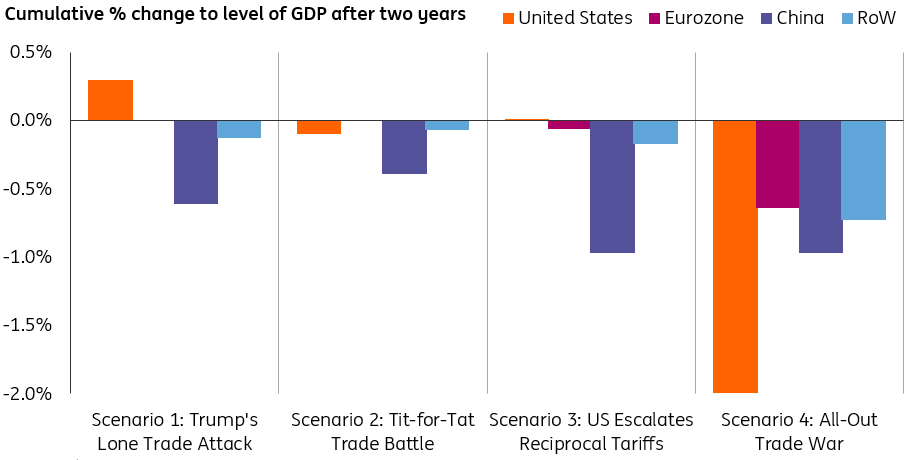

- Were an All-Out Trade War to break out, we estimate that the US will lose out most (-2.0% of GDP cumulatively over two years) – as US exporters would face higher tariffs at all borders, while the rest of the world continues trading with each other at prevailing trading arrangements.

- It is the signalling channel of US trade policy that has typically been the key driver for the USD in prior ‘trade war’ episodes. Protectionist measures implicitly signal the US administration's desire for a weaker USD – and such expectations are likely to be entrenched in FX markets until credibly broken

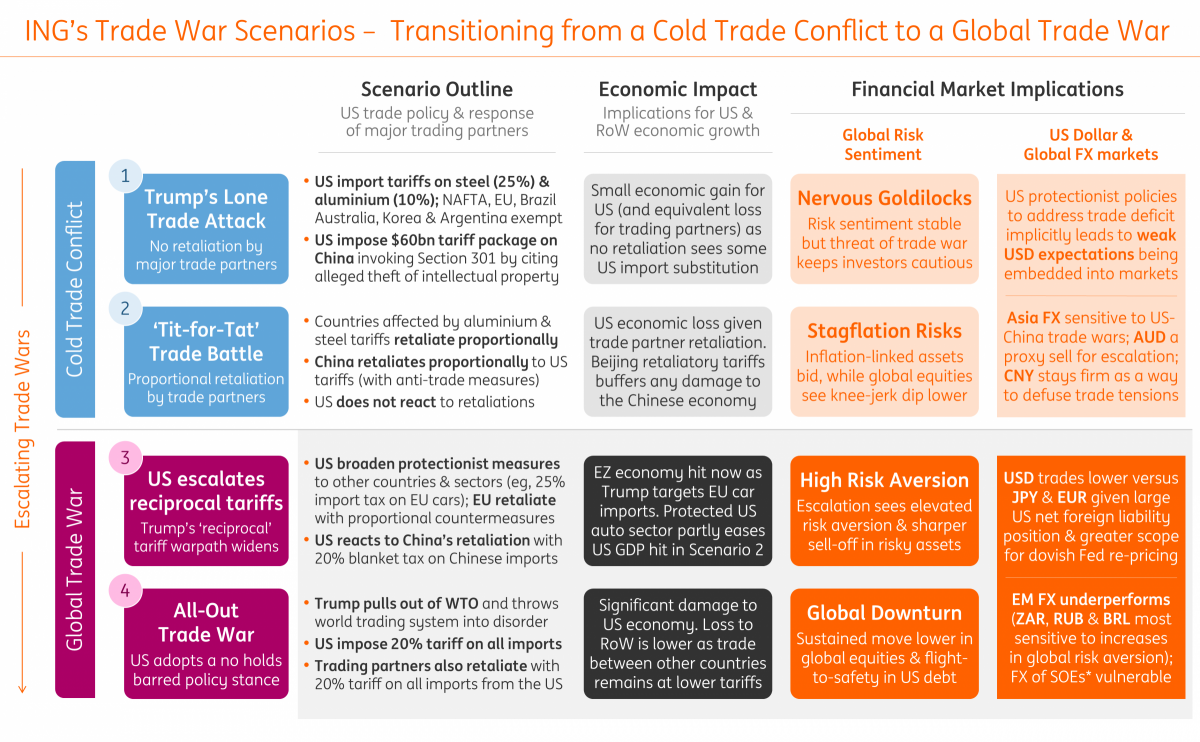

ING's Global Trade War Scenarios: Four Degrees of Escalation

The Trump administration’s decision to impose tariffs on US steel and aluminium imports and a $50-$60bn tariff package on imported goods from China – means that global trade policy has formally shifted into the realms of a protectionist world.

If countries that are hit do not retaliate to these initial US protectionist measures, the world is ‘only’ facing a one-sided contained trade attack (Scenario 1) - and not a trade war in our view. In this case, the economic effects are limited - with the Chinese economy hit the most (we estimate a cumulative 0.6% GDP loss over two years). If US imports from China, as well as steel and aluminium imports from a range of countries, are partly substituted by domestic production - we estimate that this could lead to a 0.3% increase in US GDP after two years.

Going forward, the immediate risk is whether trade partners seek to retaliate in equal and proportional measures – giving rise to some sort of ‘Tit-for-Tat’ Trade Battle (Scenario 2). While reports suggest US and Chinese officials may initially be looking to take a more diplomatic approach, the reality of unsuccessful and challenging trade negotiations means the prospect of significant countervailing measures being imposed by Beijing – beyond the trivial $3bn retaliatory tariffs on imported goods from the US already announced – is fairly high.

For global market dynamics to transition from what we see as currently being a Cold Trade Conflict (Scenario 1 or 2) to a real Global Trade War (Scenario 3 or 4), we stipulate that one of two forms of escalation must prevail:

- President Trump steps up his ‘reciprocal’ tariff rhetoric by broadening protectionist measures to other countries and sectors (we see US imports of EU cars as the next potential high-level target)

- The US administration reacts to any significant retaliatory tariffs from Beijing by imposing much harsher protectionist measures (we use the example of a 20% blanket tariff on Chinese imports).

Bold steps like these - which in conjunction we define as a US Escalation of Reciprocal Tariffs (Scenario 3) - could ultimately lead to the start of an All-Out Trade War (Scenario 4) in which all countries eventually impose a 20% import tax on all imported goods. A trigger for this could be major trading partners giving complete disregard to the international rules that currently govern global trade (and in this tail risk scenario, we assign a non-trivial risk to say the US pulling out of the WTO).

Were an all-out trade war to break out, we estimate that the US will lose out most (-2.0% of GDP cumulatively over two years) – because US exporters would face high tariffs at all borders, while the rest of the world keeps trading with each other at prevailing trading arrangements.

Estimated impact of trade wars on the GDP of major economies (4 scenarios)

Political Economy of the Dollar: Protectionist US policies reinforce weak USD expectations

Mercantilist Trump: Back with a vengeance

US politics - and a narrower focus on what is set to be a close set of midterm congressional elections in November - has been a big element of the policy shift that we’ve seen in White House in recent months. Add to this the turnover of staff and the departures of globalists (Cohn and Tillerson) - and it’s clear to see that the administration’s mercantilist and nationalist ‘America First’ policy agenda is more than just a political show.

For President Trump to truly engage with the core voter base that effectively won him the election, actions may now have to speak louder than campaign rhetoric. As such, one should expect to see trade and foreign policies dominating the White House agenda in the run-up to the November midterm elections.

Political Economy of the Dollar: US protectionism reinforces weak USD expectations

In November 1978, one Paul A. Volcker - then President of the New York Federal Reserve - wrote an op-ed piece titled ’The Political Economy of the Dollar’. In it, he writes “the United States no longer stands astride the world as a kind of economic colossus as it did in the 1940’s - nor, quite obviously, is its currency any longer unchallenged”.

This seems somewhat fitting in the current environment. It's clear from the President's tweets alone - which have seen mentions of 'trade deficits' increase almost four-fold over the last quarter - that the US administration has narrowed its economic focus on reconciling the balance-of-payments deficit. However, recent trade policy announcements - and the imposition of tactical import tariffs on selected sectors and countries - shows that the White House is now willing to take a more proactive approach to address the US external trade position.

Protectionist measures implicitly signal the US administration's desire for a weaker USD - and such expectations are likely to be entrenched in currency markets until credibly broken

The negative consequences for the US dollar are two-fold:

- The willingness to impose actual protectionist policies - and the ongoing threat from the White House that more may be yet to come - means that US policy uncertainty remains high (and hence USD assets may trade with a discount in the near-term to compensate for this uncertainty)

- The adoption of protectionist measures implicitly signal the US administration's desire for a weaker USD - and such expectations are likely to be entrenched in currency markets until credibly broken

Indeed, investors are probably finding it difficult to reconcile the case for a stronger US dollar with the Trump's administrations adamant focus to tackle the US trade deficit - especially in a 'gung-ho' manner that demands instant success. Equally, if it is the expectations channel that drives currency markets, current USD weakness is a sign that global investors are not convinced that US protectionist measures will be successful in tackling the US trade deficit (and therefore boosting US economic activity). Our empirical analysis shows that there is evidence justifying such expectations (the US economy loses out under a All-Out Trade War scenario). Equally, structural trade deficits do not get resolved overnight (or even over a Presidential term).

So, despite what standard textbooks may tell us about tariffs and exchange rates, we expect unilateral protectionist measures by the US to weigh on the dollar - with global investors loss of confidence in the US economic regime expressed through a diversification away from US assets. Were global trade war dynamics to escalate, we note the US dollar would face two additional channels of downside: (1) a repricing of US monetary policy expectations - where the 80bp of Fed tightening by end-2019 looks inconsistent with an environment where a global trade war is being played out and (2) a large US net foreign liability position (around $8 trillion) making the USD vulnerable any deterioration in the investment environment.

In such an environment, one would expect the dollar to underperform its relatively low-yielding, safe-haven currency peers like the JPY and EUR - both of which command a better net external foreign asset position and have relatively limited scope for any monetary policy re-pricing.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

26 March 2018

In Case You Missed it: One year to go This bundle contains 7 Articles