Trade & Tariffs - implications for the Fed

The intensifying trade war will impact both US inflation and growth. How will the Federal Reserve respond?

Trade tensions have been steadily escalating since the start of the year, culminating in the latest round of tariffs on $200bn of imports from China. The concern is that the situation could deteriorate further with China retaliation potentially opening the door to the Trump administration implementing tariffs on all Chinese imports. This is bad news for both growth and inflation.

Downside risks for growth

In terms of economic activity, there are negative implications for both sentiment and spending with supply chain disruption, higher costs and uncertainty on the economic implications risking a slowdown in both investment and labour hiring.

US officials counter that the fact the latest round of tariffs is starting at 10% and won’t be raised to 25% until next year – and that second part will only be implemented if China fails to make acceptable concessions – means that US businesses have time to make changes and bring production back to America. However, this in itself disrupts business activity while US companies will also face higher tariffs on their exports to China. Indeed, China shows no willingness to back down at this stage and instead is using domestic fiscal and monetary policy plus a weaker yuan to try and offset the protectionism impact on exports.

The key issue for US growth is that this isn’t the only headwind. While the US booms for now, the outlook for 2019 and 2020 is looking more challenging with a fading fiscal stimulus, higher interest rates, a strong dollar and fears of emerging market contagion further depressing global activity. As such we expect to see US GDP growth slow from around 3% in 2018 to closer to 2% in 2019 and 2020 - just when President Trump seeks re-election.

Upside threat for inflation

As for inflation, we are already starting to see rising price pressures from tariffs. If you remember, the starting point was in January with “safeguard tariffs” of 30-50% introduced for washing machines and solar panels. This was then expanded to 25% tariffs on steel and 10% on aluminium and then on 6 July President Trump announced a 25% tariff on China imports worth $50bn.

Looking at the price of washing machines we can clearly see the impact. Solar panel prices have also risen and we are likely to see inflation in other components rise. However, the impact on the headline rate of inflation has been small so far given that, for example, washing machines only account for 0.05 percentage points of the CPI basket of goods and services.

US CPI - laundry equipment price change (YoY%)

A worst case scenario

So how bad could things get for inflation? Well if we do a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation and say that annualised US personal consumer expenditure in 2Q18 was $13.87 trillion and make a broad assumption that all $505bn of Chinese imports are consumer goods we can work out a “worst case” scenario.

This simple framework implies that Chinese imports account for 3.6% of all consumer spending and if all of these products get a 25% tariff – assuming the trade war comes to a head and President Trump declares unilateral tariffs of 25% on all Chinese imports, as he has threatened – then this would suggest the headline personal consumer expenditure deflator would be lifted by 25% x 3.6% China weight = 0.9 percentage points added to headline inflation. Stripping out food and energy it could add 1 percentage point to the core PCE deflator.

The impact on consumer price inflation (CPI) would be marginally less, simply because the weight for commodities less food and energy is 19.6% of the total CPI basket versus 21% for personal consumer expenditure.

A reality check...

However, this overstates the upside risk to inflation. Firstly, the latest tariff on $200bn of imports from China is set at 10%, not 25% as assumed in a worst case scenario and we haven’t had confirmation that tariffs will extend to all Chinese imports. The staggering of the tariffs means that the initial impact on inflation is likely to be smaller this year, but inflation could be more persistent assuming the tariff is raised to the full 25% in 2019.

Secondly, not all Chinese imports are consumer goods – many are intermediate or investment goods so the end consumer isn’t guaranteed to face the additional cost.

Thirdly, we suspect that there won’t be a full 100% pass through of the tariff through to the end consumer. Instead, corporate profit margins are likely to be partially squeezed. In this regard, we also have to remember that a Chinese import has freight costs and wage costs (such as at a US retailer) attached to it before the price sticker is placed on it and it is sold in America.

Other points to consider include the possibility we see marginally lower prices from Chinese suppliers based on a desire to hold onto US market share – we assume that trade tensions will eventually de-escalate and we will return to a more normal “freer” trade environment at some point.

Then we have to consider the currency aspect. With China looking to use looser fiscal and monetary policy to support its economy and offset the negatives from trade we also expect to see the yuan weaken further. This would lower the dollar cost of exports to the US and help to partially mitigate the inflationary impact for US consumers.

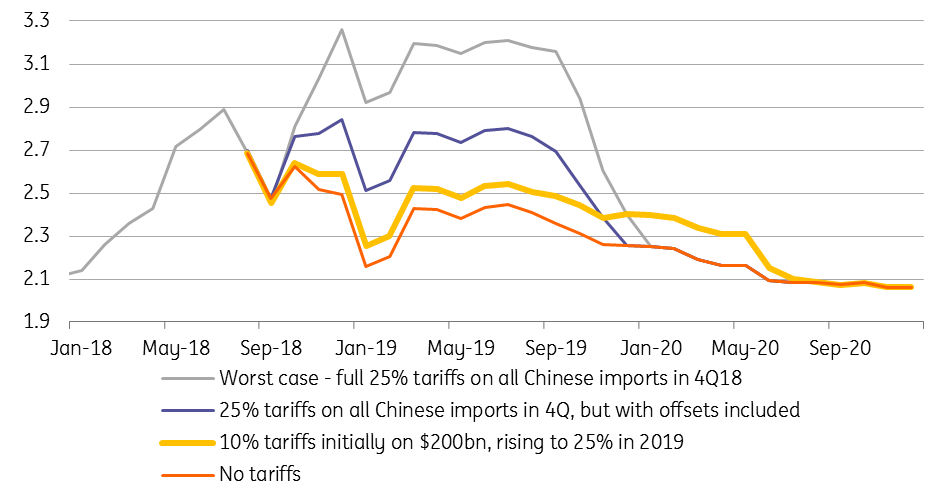

Possible scenarios for US consumer price inflation due only to tariffs (YoY%)

Growth versus inflation

Historically, tariffs are interpreted as a one-off price hike that central banks tend to “look through”, much as a VAT tax rate change. The staggering of the tariffs means that it may be slightly different this time. Taking this altogether we believe that the boost to annual US inflation is more likely to be closer to 0.2 percentage points over the next twelve months. Significant, but not enough to cause the Federal Reserve to have substantial concerns about medium-term inflation risks. We might see a similar upside risk next year if the second stage of the tariff is implemented.

If we see tariffs raised on all Chinese imports in 4Q18 we suggest headline inflation may rise by around 0.4-0.5 percentage points, before inflation converges on its previous trend in late 2019. This is more marked, but again believe the Fed will be more focused on the growth story and inflation in the medium term.

Where now for Federal Reserve policy?

The latest Federal Reserve Beige Book – an anecdotal survey of the US economy – stated that “a number of districts noted that [trade] concerns had prompted some businesses to scale back or postpone capital investment”. If this behaviour is increasingly repeated amongst US corporates, then those medium-term growth risks could intensify, which would dampen inflation pressures.

While the economy is booming right now, justifying rates hikes next week and in December, the outlook for 2019/2020 is increasingly uncertain. As such we are sticking with our view that the Fed will hike a more modest two times in total for 2019 rather than the four hikes they look set to implement this year.

Download

Download article

21 September 2018

In case you missed It: Trade tensions mount This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more