The formidable challenges facing the WTO’s next Director General

The World Trade Organisation has begun choosing its new Director General, with eight candidates in the running. As if safeguarding the rules of world trade during a pandemic wasn't challenging enough, dispute settlement needs reform, China’s status within the world trading system has to be addressed, and success partly depends on US voters in the autumn

Now that the nominations are in, the candidates to lead the World Trade Organisation are putting forward their ideas for reform and canvassing support from other member countries. The final phase of the selection process begins in September when WTO members will have up to two months to form a consensus around one of the candidates. The successful candidate will have to have a unifying vision on the major issues that are currently proving to be divisive.

Dispute settlement

The WTO’s Appellate Body, the court which hears appeals at the end of a dispute settlement process and provides the final decision in any rade dispute, has not been functional since December 2019. US action, or rather inaction, has left it without enough judges to produce rulings and take on new cases. An interim appeal arrangement has been set up by some WTO members, including the EU and China, but India and the US have not signed up.

Although dispute settlement can proceed, for now, the US needs to be brought back on board. It should be possible to address its concerns about overreach by the Body, as there is broad agreement among WTO members on the need for reform, and even on proposals to clarify the Appellate Body's role in relation to domestic law, speed up the time taken over decisions, and focus on the issues under dispute. A lot depends on the results of the US Presidential elections in November, which we'll look at shortly.

Disagreements with China

China is at the centre of several different disagreements between WTO members. It is treated as a developing country for the purposes of implementing WTO agreements, which gives it extra time to lower tariffs and subsidies. In practice, this isn’t currently a factor in the level of China’s import tariffs. However, other WTO members would prefer that China waived its rights to special treatment.

Interactions between foreign companies and China are another source of tension at the WTO. Companies have been required to give up sensitive technology and know-how as a pre-condition for investing in China or selling products there. The country's intellectual property practices have been challenged at the WTO by the US, and also by the EU and Japan. A new investment law prohibiting forced technology transfer may help to ease concerns.

China’s state support to industry is another concern for other WTO members

China’s state support to industry is another concern for other WTO members. Along with many other WTO members, China has not met WTO notification requirements around the use of industrial subsidies. The lack of transparency combined with China’s different economic model, and especially the role of state-owned enterprises in China’s economy, has led to a sense that the WTO is failing to ensure a level playing field.

China has its own disagreements with the way it is treated by the Organisation. It is classified as a ‘non-market economy’ for the purposes of anti-dumping investigations, meaning that prices of China’s products are compared to prices in other countries to determine whether dumping is taking place. Until recently, China was pursuing a WTO dispute to become recognised as a market economy.

Progress on these issues will be difficult, but China agreeing to give up developing economy status in exchange for recognition as a market economy might be the basis of a deal. For its part, China has brought forward its own proposals for WTO reform, which call for the world trade system not to discriminate in principle on the basis of (state) ownership of enterprises.

Liberalisation in reverse

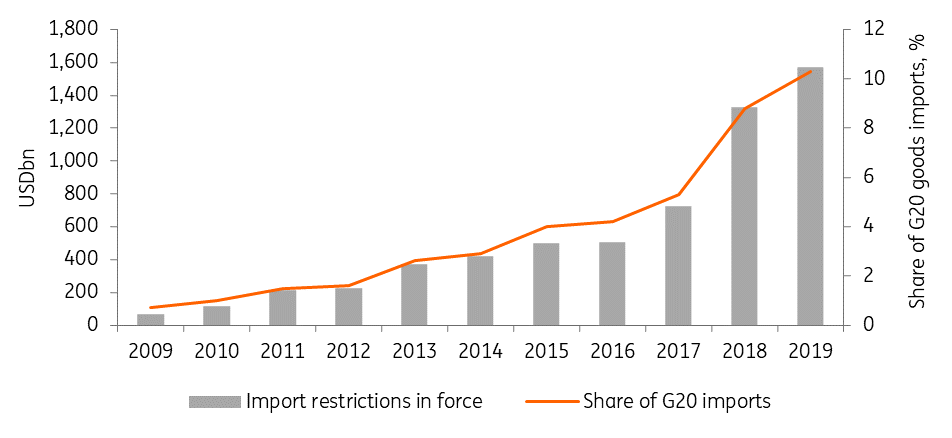

The WTO has gone a long time without achieving a successful multilateral agreement to reduce tariffs or other trade barriers (though members have agreed in recent years on improvements to trade facilitation and lowering ICT tariffs). In the meantime, trade liberalisation has seemed to go into reverse, with the escalation of the US-China tariff war and other trade-restricting measures during 2018-19, as you can see in the chart below:

Tariffs and other protectionist measures have been on the rise

Covid-19 has seen increases in both trade-restricting and trade-liberalising measures, mainly applied to medical equipment. Both types have mostly been adopted on a temporary basis, with 36% of the restrictive measures already having been removed by mid-May. As the recovery gets underway, WTO monitoring will hopefully help to ensure that the net result of the measures taken is not trade-restricting or distorting.

Covid-19 has also focused attention on the resilience of supply chains. If trade barriers go up, global value chains will become less efficient, and some production may be re-shored (though it might not reduce risks). Ongoing WTO initiatives on trade facilitation and e-commerce may help to make some progress in lowering trade barriers at the margins, while a multilateral round of tariff negotiations remains a longer-term aim.

US election uncertainty

The new WTO Director General (DG) won’t have to wait in suspense for too long to find out if the US elections are going to make their task even more difficult. If Donald Trump is re-elected as President, reforms to WTO dispute settlement are less likely to bring the US back on board, and a US exit from the WTO altogether might be possible instead. In that case, in place of multilateral negotiations, more tariff threats and bilateral negotiations will take place, with the US leveraging its might as an import market.

A Biden Presidency presents its own challenges, because Joe Biden has voiced support for some of the trade war tariffs on imports from China. But Biden appears to view international trade more neutrally than President Trump has done. A campaign pledge on supply chains involves increasing domestic production in some sectors, but also “working closely with allies”, which suggests no more tariff hikes and a less hostile attitude towards international organisations like the WTO.

A formidable set of challenges faces the WTO’s new Director General

Overall, a formidable set of challenges faces the WTO’s new Director General. The US may yet play a constructive role in reforming WTO dispute settlement, but may also be on its way out entirely. Much will depend on the outcome of the US elections in November. China’s economic model is straining many parts of the international trade system. And trade liberalisation has gone backwards in recent years, with Covid-19 giving a new impulse to protectionism. The new DG can take heart from the fact that even as the challenges have mounted up, countries have remained committed to the WTO as a forum for dialogues and disputes about world trade rules.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article