Slowdown risks mount as the Fed hits the brakes

The Federal Reserve has raised interest rates and signalled that we should be prepared for much more to come as it seeks to get inflation and inflation expectations back under control. We look for a 3% Fed funds rate, but rapid-fire hikes run the risk of an overshoot and we see a strong chance of corrective action again in late 2023

Rapid fire Fed hikes are coming

Last March the Federal Reserve told us that inflation was largely transitory. It was primarily the result of post-pandemic re-opening frictions, and in an environment of significant labour market slack, it wouldn’t need to raise interest rates before 2024. Fast forward 12 months and the story couldn’t be more different. The economy is now 3% larger than before the pandemic struck, the unemployment rate is below 4%, and inflation is proving to be far more durable, running at 40-year highs and still rising.

The Fed responded with a 25bp rate rise at the March Federal Open Market Committee meeting and signalled that 50bp rate hikes are firmly on the table at upcoming meetings. With inflation pressures visible throughout the economy, we believe the Fed will indeed deliver half-point interest rate increases at the May, June and July policy meetings.

We also expect the Fed to announce a shrinking of its balance sheet (quantitative tightening) in the second quarter. Initially, this will be via allowing $50bn of maturing assets to roll off the balance sheet in July, August and September with any additional proceeds reinvested. This could then be accelerated to $100bn from October onwards.

But too far too fast runs the risk of a miss-step

With quantitative tightening doing some of the policy tightening, we expect the Fed to revert back to 25bp hikes from September onwards. We look for the Fed funds ceiling rate to get to 3% in early 2023, but getting it higher than this could be a challenge.

With the Fed seemingly feeling the need to “catch up” to regain control of inflation and inflation expectations, a rapid-fire pace of aggressive interest rate increases heightens the chances of a policy miss-step that could be enough to topple the economy into a recession. Note that the 10Y yield on Treasuries briefly fell below that of the 2Y yield, which is taken as a warning sign of a potential recession in coming years - although history tells us it is not guaranteed. Recession is not our base case, but there are areas of vulnerability in the economy that we need to keep an eye on.

Rising mortgage rates and weak confidence suggest downside risks for housing activity

Watch housing for early signs of strains

One of those is the housing market, which has experienced 30% price increases nationally since February 2020 as demand outstripped supply. A highly stimulative environment resulted in plunging mortgage rates for a market where inventory for sale was at record lows. However, now that the Treasury yield curve has moved higher and become flatter in response to the Fed’s shifting position, this is already translating into significant increases in mortgage rates.

As the chart above shows, this is prompting a downturn in mortgage applications for home purchases, which could accelerate as borrowing costs continue to move higher. At the same time, consumer confidence is at levels on par with the global financial crisis in 2008, highlighting how the squeeze on household spending power is hurting.

With building permits and housing starts having accelerated we could conceivably swing from excess demand to excess supply over the next year, which could depress both housing activity and prices and feed back negatively into consumer activity.

Growth risks are moving more to the downside

From a domestic perspective, higher borrowing costs, a strong dollar and a potentially fraught political backdrop as we head towards the November mid-terms means that the US economy will likely face even more headwinds. In addition, supply chain strains remain while the commodity price shock resulting from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continues to reverberate around the economy. As such we have revised down our 2023 GDP growth forecast markedly from 3% to 1.8%.

Policy reversal on the cards for late 2023

A weaker growth environment and a hopefully more benign geopolitical backdrop in 2023 will help to ease price pressures and inflation could fall relatively quickly through the second half of 2023. Remember too that housing costs carry a weight of around a third of the consumer price index (CPI) and if house price growth slows sharply, this will feed through into weaker CPI inflation readings with a 12-14 month lag.

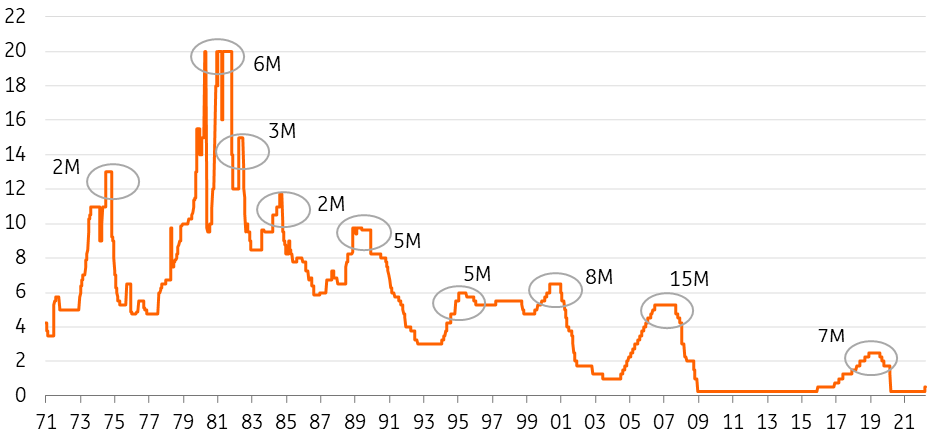

Duration between last Fed rate hike and first rate cut (months)

Interestingly, financial markets are already pricing in rate cuts in 2024 on expectations that the Fed goes into highly restrictive territory to control inflation, before relaxing policy to a more neutral stance over the longer term. We fully buy into this narrative. The chart above shows that the average period of time between the last Fed hike in a cycle and the first rate cut has only been eight months over the past 50 years. A rate hike peak in the first quarter of 2023 would on average suggest rate cuts in the fourth quarter of 2023.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

31 March 2022

ING Monthly: There’s nothing normal about the global economy This bundle contains 17 Articles