Pro-environmental behaviour: We care because others do

Climate change and environment conservation are the defining global challenges of our time (World Economic Forum 2019). While most mitigation efforts are still required at the government and industry level, behavioural change at the individual level is needed, too

The psychology behind pro-environmental behaviour

Individuals can combat environmental threats in several ways, from improving housing energy efficiency to limiting their meat consumption or riding public transportation. Several psychological motivators and barriers play a role in determining this pro-environmental behaviour (hereafter PEB) [1]. After all, conservational decisions often represent trade-offs between individual present sacrifices and collective uncertain benefits in the future.

Using data from the European Social Survey, we present new insights into the complex interplay of interpersonal, intrapersonal and external social influences on individual PEB. Central to this is the question of whether personal factors, social factors or a synergy of the two best explain why individuals do, or do not, behave pro-environmentally.

Individual behaviour is strongly influenced by the behaviour of others, and social influence could be harnessed to develop effective strategies to encourage more sustainable decisions and climate resilient behaviour

We highlight three main findings:

- Social factors including peers’ behaviour are among the strongest motivators of personal environmental decisions.

- The sense of social efficacy not only improves personal PEB directly, but it also does so indirectly by enhancing the sense of self-efficacy of individual actions.

- Individual concerns about energy affordability can turn into a barrier to PEB when such concerns increase excessively.

These findings have important implications. They demonstrate that individual behaviour is strongly influenced by the behaviour of others, and that social influence could be harnessed to develop effective strategies to encourage more sustainable decisions and climate resilient behaviour.

Data and framework

We use data from Round 8 of the European Social Survey (ESS) conducted in 2016-2017, which included two unique modules covering questions on individual and public attitudes to climate change as well as on energy preferences, concerns and use behaviours [2]. Our sample is composed of approximately 30,000 individuals, aged 15-85, living in 21 European countries [3].

We analyse (1) how personal and social-related factors explain individual pro-environmental behaviour, and (2) the extent to which these factors interact with each other as barriers or motivators for positive environmental behaviour. We use the value-belief-norm framework (Stern 2000) for this analysis and extend it with personal beliefs and norms related to the behaviour of others.

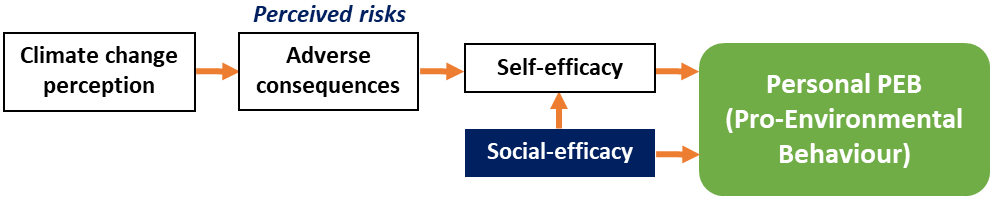

Figure 1. Value-belief-norm theory (Stern 2000), adapted by the authors

In Figure 1, the fundamental idea that personal PEB is driven by personal values, beliefs and norms about the individual himself is represented in the white boxes. The dark-blue boxes add several social-related factors to the original model, following the literature on the influence of social norms and social comparisons on environmental decision making and behaviour (Frey & Meier 2004; Schultz et al. 2007; Allcott 2011; van der Linden 2015; Lede and Medealy 2018). The specific definitions and measures we apply to the ESS data are shown in Figure 2.[4]

Figure 2. Value-belief-norm definitions and measures

What factors determine personal PEB?

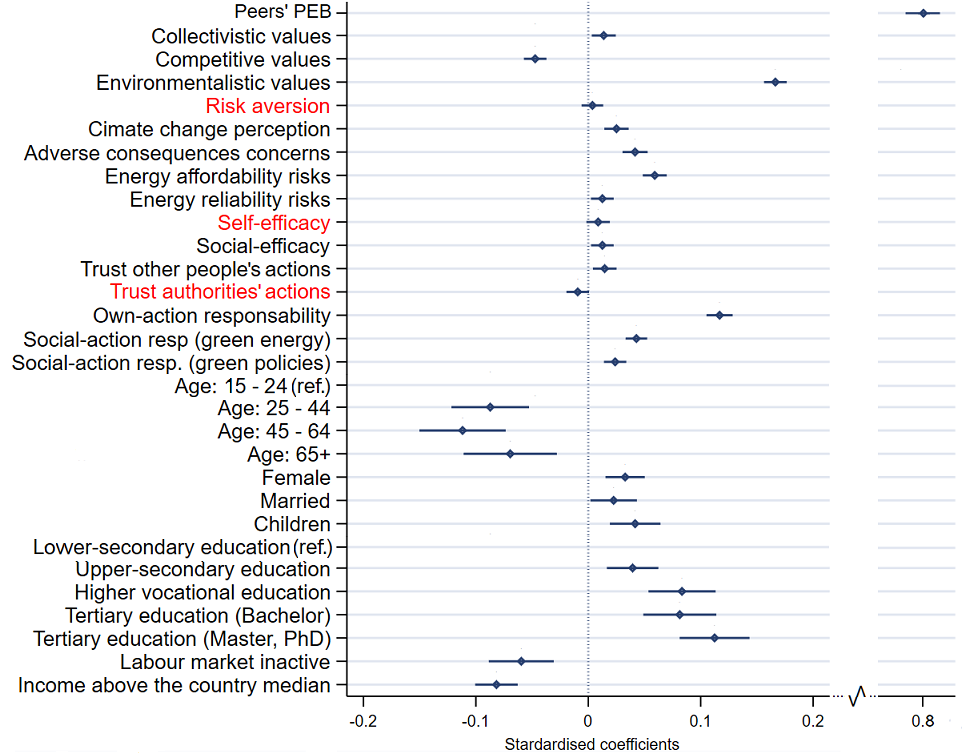

To better understand how personal and social related factors explain individual PEB, we present in Figure 3 the empirical results of the framework proposed in the previous section [5].

People with more competitive and individualistic values as well as those who are older or with incomes higher than the country median seem to experience more barriers towards green behaviour

Our findings suggest that peers’ PEB (β=0.79, p=0.00), personal environmentalistic values (β=0.17; p=0.01), and the feeling of being personally responsible for climate change (β=0.12; p=0.01) are the strongest motivators of individual green behaviours. Individual PEB is also enhanced with a stronger sense of social-action responsibility, social efficacy, trust in other people’s actions, collectivistic values, and perceived risks associated to climate change. Adding to the social-related factors, the household context (living with a partner and/or having children) also contributes to better environmental behaviour. In contrast, people with more competitive and individualistic values as well as those who are older or with incomes higher than the country median seem to experience more barriers towards green behaviour [6].

Figure 3. Determinants of individual Pro-Environmental Behaviour

As shown in Figure 3, both the belief that climate is changing and being concerned about energy affordability separately improve personal PEB. However, we find further evidence that the interaction between these two perceptions can turn into a barrier for green behaviours: individuals convinced that climate change is real are much less motivated to take action when their concerns about energy affordability become too large. This highlights the importance of affordability matters in shaping people’s green behaviour; when such perceived economic risks increase excessively, people can turn their sense of individual responsibility into a defensive attitude towards others (including governments) as the ones responsible to combat climate change (Kollmuss & Agyeman 2002).

The power of peers' PEB

As mentioned in the previous section, the strongest motivator of individual PEB is the personal exposure to others who behave in a pro-environmental manner (peers’ PEB). This peer-effect reflects the power of a social norm or social pressure in stimulating individual green behaviour (Cialdini et al. 1990; Lindenberg & Steg 2007; Schultz et al. 2007).

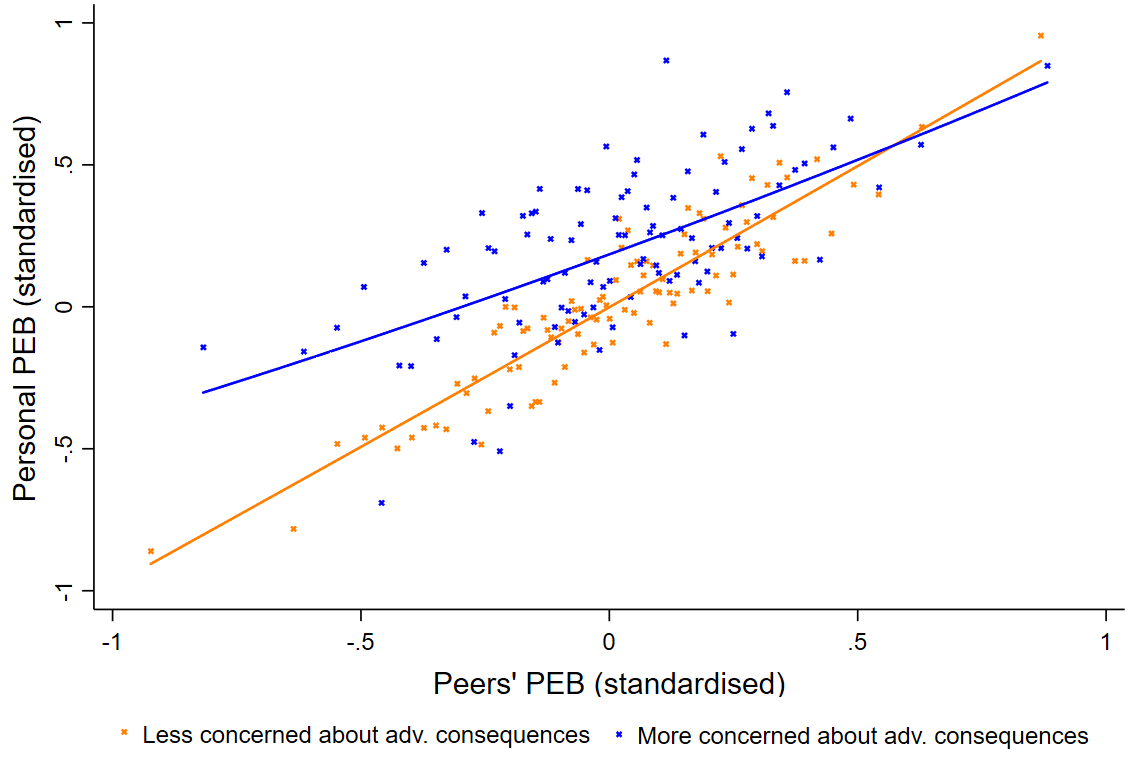

Interestingly, we find further evidence that the positive influence of peers’ PEB on personal PEB is larger among individuals that are relatively less concerned about the risks that climate change brings about (see Figure 4) [7]. This suggests that social behaviour comparison or social norms could act as an extrinsic PEB motivator for those who are less intrinsically motivated. As implied by Figure 4, greater social pressure could enhance the PEB of those who are less concerned about the adverse consequences of climate change, even to the point that their behaviour improves more than that of those more intrinsically motivated. This is a typical example of the bandwagon effect, a psychological phenomenon where people do something primarily because of other people’s behaviours, regardless of their personal beliefs which may even be ignored or overruled (Corneo & Jeanne 1997; Frederiks et al. 2015).

Figure 4. Effect of peers’ PEB on personal PEB by concerns about the adverse consequences of climate change

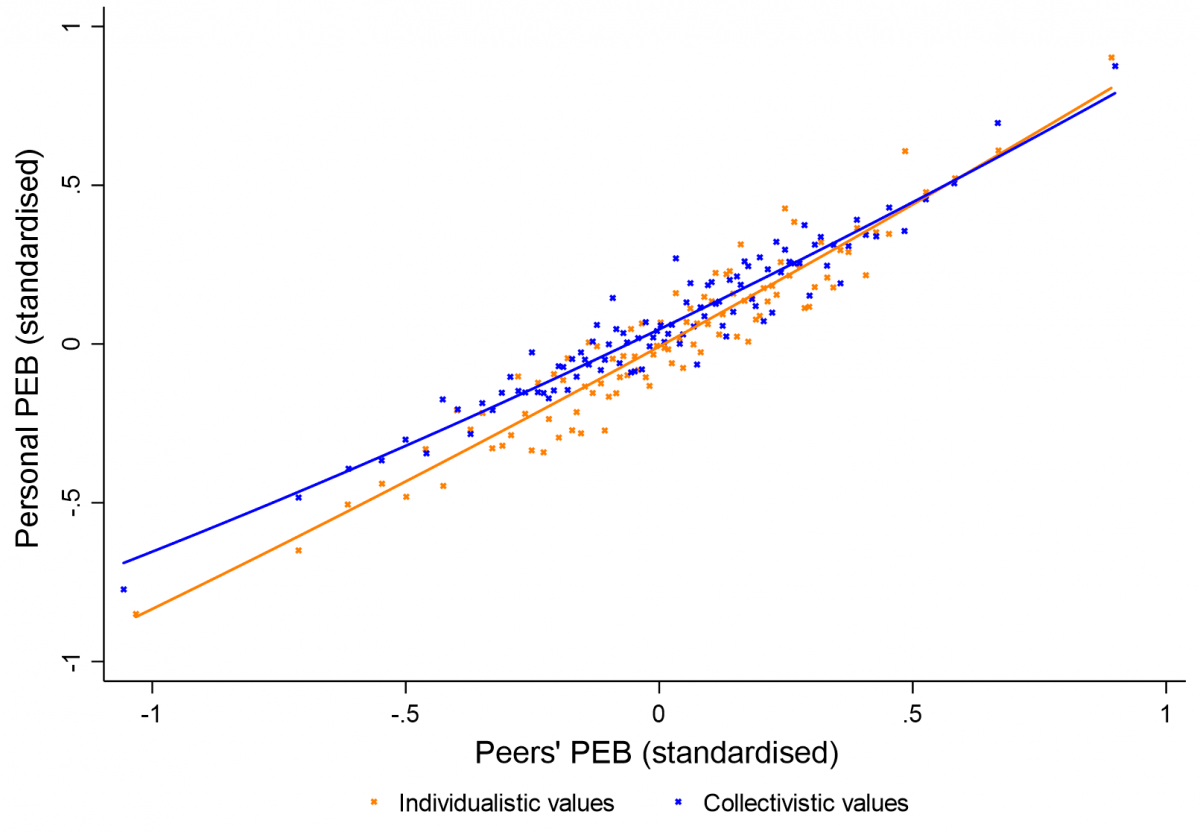

As shown in Figure 5, we also find that the motivating effect of peers’ PEB on personal PEB is slightly stronger among people with individualistic values rather than collectivistic ones [8]. For people with more collectivistic values, personal norms (own-action responsibility) seem to be the most important moderating factor of PEB. Further analyses suggest that the probability of individualistic people to show positive behaviour towards the environment is conditional on their expectation that the government does so as well. This is also known as the ‘conditional cooperation’ effect observed in voting, teamwork and tax compliance behaviours (Gächter 2006).

Figure 5. Effect of peers’ PEB on personal PEB by collectivistic-individualistic values

Self-efficacy vs. social efficacy as motivators of PEB

In Figure 6, we illustrate the main result from the self-efficacy and social efficacy moderation and mediation analyses in relation to individual PEB.

- First, we find that self-efficacy – the belief that individual actions can make an impact to reduce climate change – positively affects personal green behaviour but only if individuals believe that climate change is actually happening (climate change perception) and at the same time are concerned about its adverse consequences. If these beliefs are not present, the influence of self-efficacy on personal PEB appears to be null. This might be because many people consider climate change risks as well as the benefits of mitigating them to be uncertain and mostly in the future or geographically distant, both reducing the perceived ability and actions to mitigate climate change (Leiserowitz 2005; Swim et al. 2009) [9].

- Second and more interestingly, we find that social efficacy – the belief that people as a group can make an impact on climate change mitigation – can directly motivate PEB, even when there are no beliefs or concerns about climate change risks. According to our findings, social efficacy is so powerful that it not only improves PEB directly, but it can also mediate the effect of self-efficacy on individual PEB. This finding is consistent with the psychology of climate change as a collective problem, as opposed to a private one, in that individuals tend to feel easily discouraged by the seemingly insignificant effects of personal behaviour. Therefore, psychological factors related to the impact of joint effort seem to play an extremely important role in motivating both personal environmental behaviour and the sense of efficacy of individual actions (Keizer et al. 2013; Frederiks et al. 2015; Williamson et al. 2018).

Figure 6. Effect of self-efficacy and social efficacy on personal PEB

If others care, so do we

We have provided insights into the interplay of individual and social-related factors as motivators or barriers of personal environmental behaviour. We highlight the finding that the pro-environmental behaviour of peers as well as the belief that joint efforts can make an impact on climate change reduction are strong motivators of personal green behaviours. This finding implies that social comparisons or social norms could act as extrinsic drivers of environmental behaviour, especially for those that are less intrinsically motivated (e.g. due to stronger individualistic values, climate change denial or too much concern about energy affordability).

Pro-environmental behaviour of peers as well as the belief that joint efforts can make an impact on climate change reduction are strong motivators of personal green behaviour

The extent to which social forces can drive individual pro-environmental behaviour significantly depends on personal values and beliefs; all factors likely to differ across cultures and countries. To design effective behavioural mechanisms to promote pro-environmental behaviour, further research on these potential differences is needed. In addition, there is more to learn about drivers and barriers of environmental behaviours beyond those investigated in this study, including for example cognitive biases such as loss aversion and temporal discounting, external rewards or punishments, and the objective circumstances under which environmental decisions take place (Anable et al. 2006; Frederiks et al 2015).

On a final note, many people say that global problems require global actions. This paper shows that even if climate change might not be perceived by everyone as a global problem that requires individual action, the sense of social responsibility could stimulate individual behavioural change. It seems that the more we believe or see that others care about the environment, the more we as individuals care as well.

Footnotes

[1] Pro-Environmental Behaviour (PEB) is defined as the intensity of current individual behaviours to reduce energy use, that is, behaviours related to daily life housing, transport, consumption, etc.

[2] The ESS is a cross-national survey conducted face-to-face every two years in Europe since 2001. It is representative of the population of each of the participant countries, following a strict random probability sampling. Further details on the survey and freely downloadable data are available at www.europeansocialsurvey.org/data/.

[3] Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Island, Italy, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

[4] The factors’ structure was validated in a principal component factor analysis. To facilitate the interpretation of results, all variables were standardised.

[5] The results presented in this paper are based on linear regressions. All regressions account for several demographic covariates, country-region fixed effects, robust-clustered standard errors, and post-stratification weights including design weights.

[6] Strikingly, neither risk aversion nor self-efficacy or trust in governments’ action to reduce climate change seem to have a significant direct impact on individual PEB. In the following sections we dig deeper in the possible explanations of this result.

[7] A set of interacted linear regressions were used to test for this moderation effect.

[8] Note that this effect pertains to individualistic vs. collectivistic values at the individual level. The effect does not hold at the country level when testing the differential effect of peers’ PEB in more individualistic or collectivistic social environments.

[9] Because a sizeable 10% of people in our sample does not believe that climate change is happening at all and another 27% report not to be concerned about climate change, we observe an overall null effect of self-efficacy on PEB in our basic model (see Figure 3).

"THINK Outside" is a collection of specially commissioned content from third-party sources, such as economic think-tanks and academic institutions, that ING deems reliable and from non-research departments within ING. ING Bank N.V. ("ING") uses these sources to expand the range of opinions you can find on the THINK website. Some of these sources are not the property of or managed by ING, and therefore ING cannot always guarantee the correctness, completeness, actuality and quality of such sources, nor the availability at any given time of the data and information provided, and ING cannot accept any liability in this respect, insofar as this is permissible pursuant to the applicable laws and regulations.

This publication does not necessarily reflect the ING house view. This publication has been prepared solely for information purposes without regard to any particular user's investment objectives, financial situation, or means. The information in the publication is not an investment recommendation and it is not investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure that this publication is not untrue or misleading when published, but ING does not represent that it is accurate or complete. ING does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication. Unless otherwise stated, any views, forecasts, or estimates are solely those of the author(s), as of the date of the publication and are subject to change without notice.

The distribution of this publication may be restricted by law or regulation in different jurisdictions and persons into whose possession this publication comes should inform themselves about, and observe, such restrictions.

Copyright and database rights protection exists in this report and it may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any person for any purpose without the prior express consent of ING. All rights are reserved.

ING Bank N.V. is authorised by the Dutch Central Bank and supervised by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). ING Bank N.V. is incorporated in the Netherlands (Trade Register no. 33031431 Amsterdam).