Poland: No fireworks from S&P or Fitch

This Friday, S&P and Fitch will review Poland’s rating. We expect no change given the standoff with the European Commission over a judiciary overhaul. While S&P's decision may disappoint some investors, the market is already pricing Polish government bonds above the level consistent with S&P's BBB+ rating, so the impact on prices should be limited

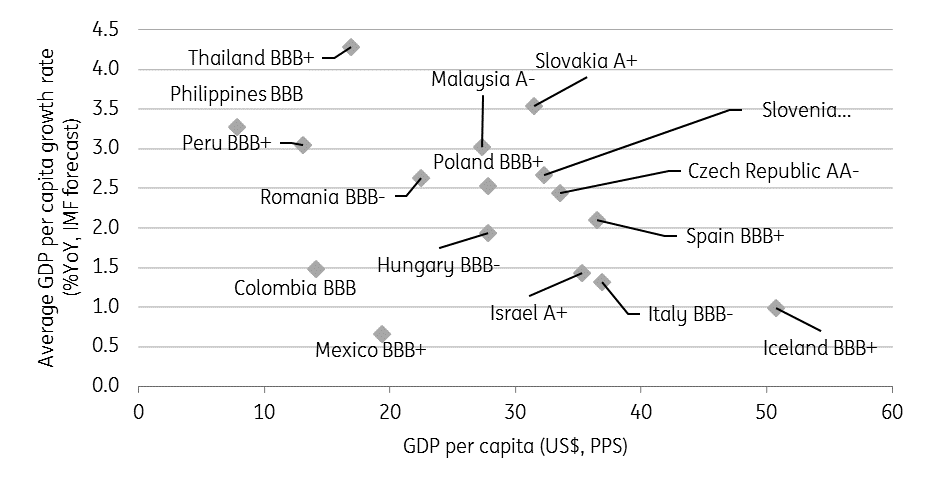

Fitch has maintained an A- rating (with a stable outlook) since 2007, while S&P downgraded Poland to BBB+ in 2016 (the lowest of the three key agencies), citing institutional risks. In April, S&P changed its outlook to positive (from negative), which some investors took as a sign of an imminent rating upgrade. While macroeconomic variables suggest S&P should rate Poland more favourably (see chart 1), we expect the rating to remain unchanged as none of the institutional factors behind the 2016 downgrade have dissipated.

Fig 1: GDP per capita and its growth rate (%YoY)

Macroeconomic fundamentals are better compared to other BBB peers

Macroeconomic developments have easily surpassed all of the agencies forecasts, both on GDP and the fiscal side (leading to a series of upward revisions). Still, both the market consensus and our own forecasts suggest even better growth and deficit figures (close to 5% year-on-year and below 1.5% of GDP, respectively, for 2018) than the latest S&P estimates (4.5% YoY and 2.0% of GDP).

The better assessment of economic conditions this year and next is linked to structural improvements. Estimates for the structural balance by major international financial institutions (e.g. the IMF, European Commission) have been revised up from 2017. They are currently hovering around 2% of GDP vs. approximately 2.7% a year ago. It's a similar story with the so-called potential rate of long-term GDP growth. Recent European Commission forecasts suggest an upward trajectory to 3.6% YoY in 2019. We expect rating agencies to maintain more pessimistic views on these figures, especially on potential output. Moody’s, for example, cited a long-term growth estimate of 3%, therefore postponing potential upgrades.

Similarly, both rating agencies and financial institutions tend to provide excessively pessimistic external balance forecasts (current account as a percentage of GDP), which are routinely upgraded. We argue such predictions are still conservative. For example, the IMF assumes a deficit of close to 1.5% of GDP in 2020, while even at the top of the business cycle, the balance remains neutral. Looking into the agency’s methodology, a convergence towards a neutral external balance suggests an upgrade of the macroeconomic assessment, but such revisions are more likely in 2019.

Institutional assessment will weigh negatively on rating

Still, while macro figures are fine, the institutional environment (particularly the judiciary overhaul) is likely to remain a concern. While the European Commission seemingly abandoned plans to follow the Article 7 procedure via the European Parliament (fearing insufficient support), the conflict has moved to the European Court of Justice. The EC hopes for a swift resolution, forcing the Polish government to partially reverse some of the judiciary overhaul changes. Moreover, a looming parliamentary election may be a risk – one cannot exclude some generous fiscal spending to sway public support (even if no key items are planned for 2019 so far).

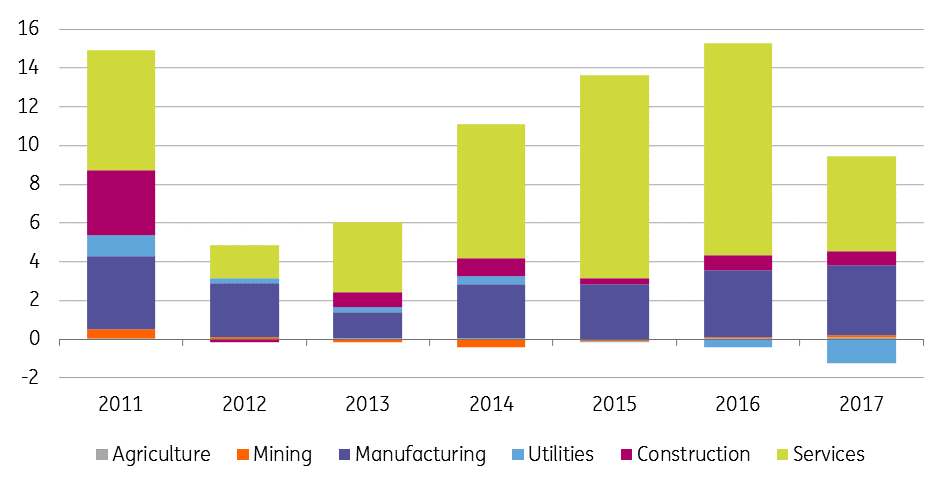

All the agencies also consider a weaker capital inflow as a risk for Poland’s rating. This risk has not materialised so far. Financial assets were under pressure only temporarily in 2016 and more than recovered later on. FDI largely tracked a general trend in central and eastern Europe (see chart 2), seemingly unaffected by the political turmoil.

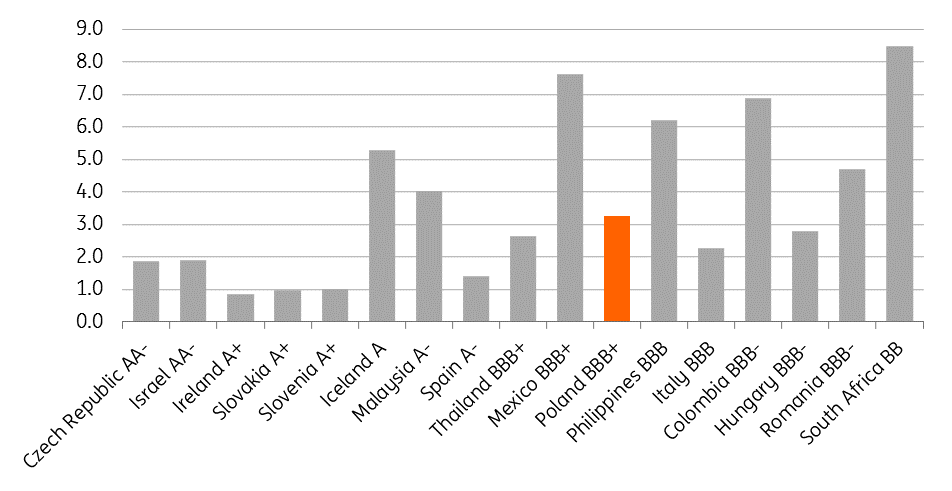

Market positioning suggests that S&P (and Fitch) decisions will have a limited impact on pricing in any event. Polish government bonds are already priced above average for peers with a similar S&P rating (see chart 3). This suggests that investors consider S&P's assessment as unjustified and are unlikely to change positions regardless of whether the agencies assessments match current valuations.

Fig 2: FDI inflows by sector (EURbn)

Fig 3: 10-years Government Benchmark yield (Annual Average)

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more