Eurozone’s periphery in peril

The initial shock to the eurozone economy from the Covid-19 pandemic was symmetric as all countries went into lockdown roughly around the same time. But the pace of recovery will be far more asymmetric, with many peripheral economies at risk of a longer-lasting slump

Most drivers of the speed of recovery favour the old “core” countries

Going over a variety of factors that play a role in the speed of recovery from the crisis, a rather consistent picture emerges. There are very little scenarios imaginable in which southern Eurozone economies manage to recover as quickly as their northern counterparts. Below we’ll list the drivers we deem important and show the differences between northern and southern counterparts.

Looking at a variety of factors that we deem important for the speed of the recovery of this corona crisis, we find a much weaker base for a swift recovery in the southern eurozone economies than in the north.

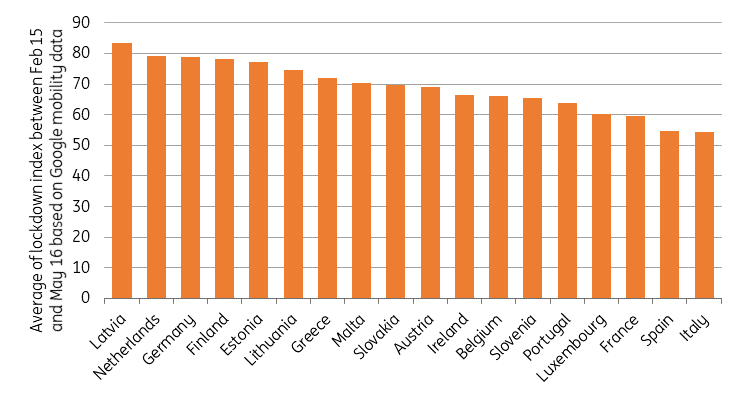

Take the depth of the lockdown for example, which as can be seen in chart 1 has been much more severe in Italy and Spain than in Germany and Netherlands. The more severe the downturn, the more likely it is that lasting damage to the economy has occurred, increasing the chances of a slower recovery. That is especially the case when safety nets and emergency fiscal spending are weak, which is also the case in Spain and to a somewhat smaller degree in Italy, Portugal and Greece for example. Northern economies, therefore, seem much better prepared for a deep downturn.

The lockdown impact has been largest in Italy, Spain and France

Specific to this crisis, we see that the sectoral composition of periphery countries does not favour a fast recovery. Countries more reliant on tourism for example are likely to experience a weaker recovery as that sector will likely experience a slow bounce back from the lockdown. The same holds good for countries with more small businesses and businesses with weaker financial buffers as they are more likely to go bankrupt in times of no income or reduced income. Financial buffers are also important for households in the recovery, because countries with lower household buffers tend to see weaker spending in the recovery. Out of the factors above, countries like Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece tend to perform weaker than their northern counterparts. Only in terms of household buffers do Germany and Netherlands come out lower on the list. A final factor taken into account that would put northern economies at a disadvantage is openness of the economy as a slow recovery of world trade would hamper economic recovery as well.

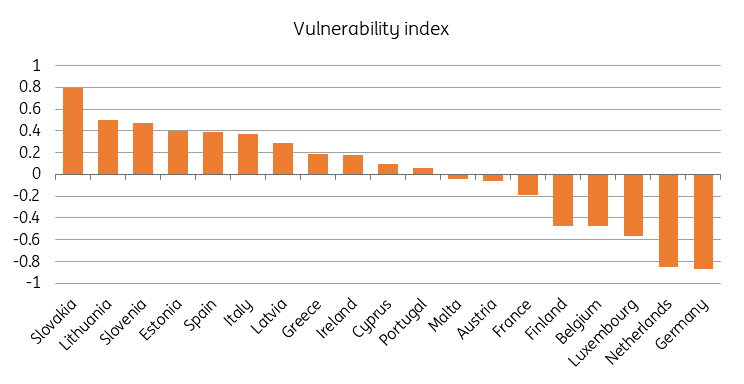

The old eurozone periphery is most vulnerable to a prolonged slump

Taking all of these factors together, we can create an index measuring vulnerability to a prolonged corona slump. Without applying any weights, the index is essentially agnostic about which factors will weigh the most. The countries that are most vulnerable according to the index are the CEE countries, followed by Spain and Italy, while Portugal, Greece, Slovenia and Cyprus also rank as more vulnerable than average. The countries that are more likely to bounce back quickly are all the northern eurozone economies. This sounds a lot like the old familiar lines drawn around the “core” and “periphery” of the euro crisis.

The “core” is better set up for a swift recovery than the “periphery”

A longer recovery in southern eurozone economies could have worrying implications

If indeed southern eurozone economies are in for a much longer economic slump on the back of the Covid-19 crisis, this could have worrying implications from a debt perspective. While some countries have committed to smaller than average support packages, debt as a percentage of GDP will still be significantly higher if GDP does not recover for a longer period of time. It is not unthinkable that debt-to-GDP ratios rises faster by mid-2021 in countries that have spent a smaller share of GDP on the crisis, simply due to the diverging trends in economic growth.

These concerns about debt levels already seem to have played a role in the size of the support packages by individual governments. The size of announced fiscal spending by country so far links best with market yields for government bonds and the level of government debt prior to the crisis, rather than the depth of the lockdown or automatic stabilisers, for example. This indicates that despite the historic steps taken within the EU, such as activating the “general escape clause” in the stability and growth pact by the European Commission and the ECB's PEPP bond buying programme, governments have still been wary about longer term debt worries while fighting this crisis.

The recent discussion and latest proposals on a European Recovery Fund indicate that there is a growing awareness of the longer-term problem an asymmetric recovery could create. A pan-European fiscal response on top of the already agreed package of European Investment Bank support, loans for short-time unemployment schemes and a possible European Stability Mechanism credit line, could alleviate this problem to a certain degree. This is particularly true if the fund uses grants rather than loans, though there could still be a potential problem with moral hazard. The message to financial markets concerned about debt sustainability and euro break-up risk would be loud and clear: the EU leaves no country behind.

Download

Download article11 June 2020

June Economic Update: Hope returns despite the huge challenge ahead This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more