Covid-19: Spending, austerity and the Dutch experience

Dutch public finances provide ample room for temporary fiscal stimulus in the Covid-19 crisis and support for fiscal austerity is waning among economists. This is in stark contrast to the aftermath of the global financial crisis when the Dutch rushed into austerity and urged others to do the same

The Netherlands earned a reputation for prudence after the financial crisis

Like other governments across the world, the Dutch government responded to the global financial crisis with a stimulus package, but a few years later the Netherlands, often together with Germany, became famous, if not infamous, for significant austerity and reform measures, and strong advocacy for such policies.

Initially, there was a lot of support for this approach among Dutch politicians and even the general public. Many Dutch economists argued in favour of cutting expenditure and increasing taxes, supporting the government for its “fiscal prudence”. Support was certainly not unanimous, but those warning against the impact of prudence were then still in a minority.

In the end, the Dutch economy experienced another recession in 2012-2013 and only saw GDP climb back to its pre-crisis level in 2015.

Taking the long-term perspective on sustainability

In the years that followed, business cycle momentum picked up further and public debt started to fall quickly, leading to a low public debt ratio of about 49% of GDP in 2019.

During this period, ING Economics Research discussed how Dutch public finances should be viewed with a number of academic economists, and in particular which indicators are relevant in both good and bad times. At the time, many economists emphasised the importance of having a long-term perspective on the sustainability of public finances.

They also stressed that in times of crisis, confidence indicators in financial markets should be monitored alongside the sustainability balance, given that the European sovereign debt crisis had made financial stability a core part of the debate. The possibility of rising risk premiums on Dutch government debt still played a significant role in the debate in 2017. Via this channel, higher government spending would risk becoming ineffective by crowding out private spending.

Consensus about initial reaction to support the economy

As Covid-19 has made new demands on public finances, here at ING we've conducted another round of interviews with eleven Dutch-speaking academic experts on topics around public finances and macroeconomics. Among those we interviewed there was unanimous consensus about the large fiscal support packages that the Dutch government has delivered up to now.

Given the economy experienced an abrupt and large disruption, which is expected to be temporary, the government was right to limit the economic damage. Many of the economists mentioned keeping unemployment low as an important short-term goal.

More than enough room for temporary support

According to these economists, the increases in public debt associated with the support measures are not a concern. Because annual revenues and expenditures in the Netherlands are roughly in balance, the public debt ratio (public debt as % GDP) increases only as a one-off as a result of the temporary support measures.

Even after the additional support package (the third announced on 28 August for the period between October 2020 – June 2021) the debt ratio is expected to remain at an acceptable level.

Many economists think there is no identifiable hard limit for the public debt ratio

Many economists that we interviewed think that there is no identifiable hard limit for the public debt ratio, but some mentioned 70%, 80% or 90% of GDP as safe limits. According to the latest official forecasts by the Netherlands Bureau of Economic Policy Analysis – the debt ratio remains only at 60% GDP in 2020.

A rising risk premium is not seen as the most relevant factor currently to take into account.

No rush towards austerity now

But what should we expect when the Covid-19 crisis is over?

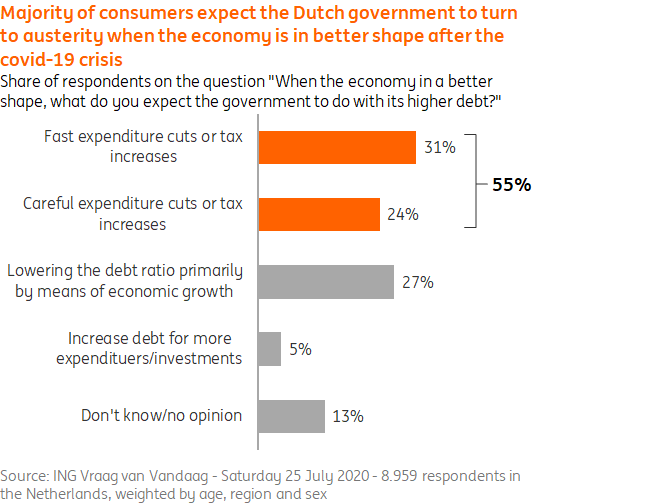

Based on the austerity experience in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the majority of ING’s daily poll of retail clients expect the government to cut expenditure or raise taxes again when the economy is in better shape, suggesting a view among the wider public that austerity will resume.

Expectations of austerity

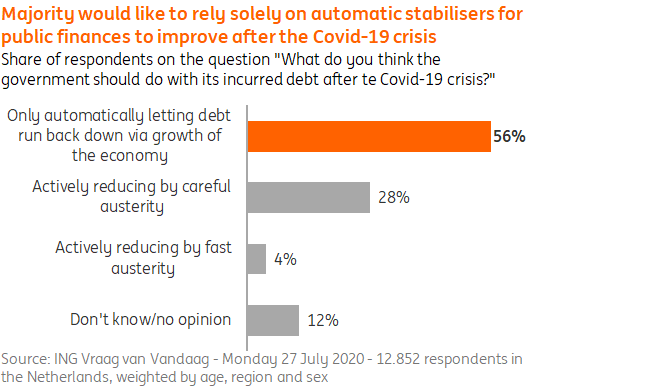

However, consumers do not want active austerity measures after the crisis. The majority prefer letting debt run back down automatically through the growth of the economy, counting on automatic stabilisers rather than discretionary policy.

What to do about debt

Economists are divided on whether government expenditure should be lowered actively beyond the expense of support measures after the Covid-19 crisis. Some economists support waiting until the economy can stand on its own feet again before terminating government support programmes, but would then start to actively reduce debt. The reasoning is that this would create a buffer for the next recession – a debt to GDP ratio well below 70, 80 or 90% GDP.

Those asking for discretionary measures call for for a very gradual approach, with some saying lowering the debt burden could be spread over multiple decades. Another group of economists claim that no discretionary interventions are necessary at any point. All in all, amongst economists there is no support for significant interventions in the short term to repair public finances.

None of the economists we interviewed is currently worried about Dutch public finances, in part because of the low-interest rate and solid economic and fiscal fundamentals.

Disagreement about future support and concerns about productivity support

There may be ample room for continued fiscal support, but there is a real difference in opinion among economists about the role of government in such continued support in the near future. The economists we interviewed are concerned about productivity in the longer term, not least because it determines the future tax base.

A crucial question is whether the economy will manage to recover production that has been lost

A crucial question is whether the economy will manage to recover production that has been lost. Many of the economists fear we won't be able to catch up with that even when the economy starts growing again, leaving some output and income permanently lost (see the orange line in the chart). Some of the economists even see the possibility that productivity will grow more slowly, making the losses grow each year (as you can see in the purple line).

Although the economists could not exclude the possibility of a full recovery and even a boost to economic growth, mostly due to increased digitisation, there are a few who attached a high likelihood to these scenarios.

Covid-19's long lasting effects

Some economists view reallocation as an urgent priority

One group of economists takes the view that it's about time to restructure the economy, involving workers and firms starting to focus on areas with more long-term growth potential.

These economists point to the fact that the crisis may last a long time and has already led to behavioural changes which could be permanent, such as more working from home and online shopping. They emphasise that restructuring promptly will yield more economic growth over the long run. They stress the need to reallocate the means of production from existing activities to growing sectors and businesses as soon as possible.

This requires the timely unwinding of public support measures. They believe that freezing the economy in its pre-Covid-19 state in the end is more of a drag to productivity than the temporary loss of production that comes with disruptive restructuring.

Other economists seek to limit unnecessary structural damage

An opposing view highlights the risk of terminating too quickly the government’s support to the economy. In this view, the bulk of economic activities from the ‘old’ economy is still viable, and will unnecessarily be lost for good if they are not temporarily helped to survive.

The biggest risks to long-term productivity arise from unemployed workers losing skills and knowledge, and innovations and investment being put on hold in the case of a fast reduction of government support.

The networks which produce and distribute goods and services may be destroyed if they are not maintained. All of which needs to be reinvested after the crisis if public support packages are terminated too soon.

Better to be safe than sorry

In our view, at this stage of the Covid-19 crisis, it is better to be safe than sorry.

The potential damage caused by withdrawing government support too early is much larger than the potential upside of earlier reallocation. Assuming that the virus is brought under control and social distancing measures are eventually phased out, this will mean many ‘old’ business models will be fully viable again. Providing government support to the economy now will save production capacity and skills having to be built back up from scratch.

The gradual change in opinion in the Dutch economy is relevant for international debate too

It is still unclear which skills, knowledge, goods and services have a place in the post Covid-19 economy, but there will come a point where this is easier for all agents in the economy to see. Some reallocation will eventually have to happen and that is also good for long-term productivity. However, it is easier to start new businesses, perhaps with new business models, when aggregate demand is stronger than while uncertainty about the new normal remains high and demand is weak.

Extending government support will delay the required transition (of shopping streets, for example). However, it will still happen, so the impact on productivity growth will take effect, albeit a little later. And last but certainly not least, supporting the economy for an extended period prevents a lot of human suffering, since research shows that unemployment has a major impact on human well-being.

The gradual change in opinion in the Dutch economy is relevant for international debate too. Since opinion on public finances shows fewer signs of public debt aversion than we have seen previously, especially in politics.

Premature austerity in the Netherlands seems much less likely than during the global financial crisis.

Acknowledgement

The following economists were interviewed but the final conclusions are entirely those of ING Economics Research.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

10 September 2020

Brexit, the pound, and the ECB’s possibly risky verbal balancing act This bundle contains 7 Articles