Korea – Just when it all started to look more promising

Korea had a bad 2019, but 2020 was shaping up to be better. The Covid-19 outbreak has made sure the first half of 2020 will be a disaster and the rest of the year pretty miserable too. We don't really know how much permanent and collateral damage the coronavirus will wreak, but 2021 is now the real prize

Korea had a bad 2019. Hit by collateral damage from the US-China trade war, a politically motivated trade spat with Japan and perhaps most importantly, the slump in global demand for technology goods.

But 2020 was shaping up to be better. The phase-one trade deal was signed in mid-January, and there had been some more optimistic signs from the technology sector towards the end of 2019. 2020 was on track to deliver an adequate growth rate of GDP, though perhaps not an amazing one.

The Covid-19 outbreak has made sure that even this conservative possibility is gone. And there is now little chance that the first half of 2020 will be anything other than a disaster. There is still a chance that the second half can be salvaged, but 2021 is now the real prize.

Before zooming in on the Covid-19 outbreak and its implications for Korea, it is worth setting out how the backdrop for the economy was looking before people started to get sick. This is what we may revert back to later this year if the disease begins to relent.

Firstly, the trade war. Although a lot of poor Asian performance in 2019 has been blamed on the trade war, we're not convinced this was the biggest headwind to Korean growth in 2019.

Looking at it in terms of export growth numbers, “other-Asia” was not the weakest segment for Korean exports last year, and within Asia, China was not the weakest export partner in terms of export growth either. In fact, although the growth rates were relatively modest, China was still towards the top of the pack.

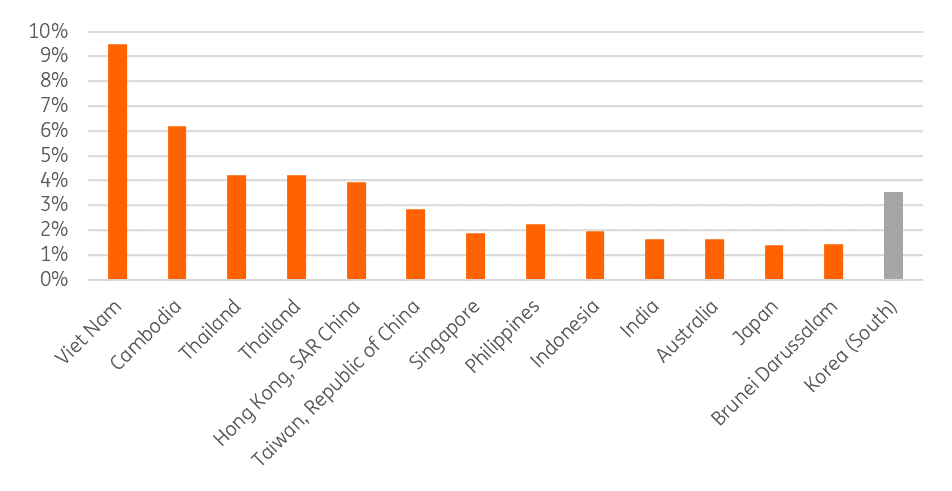

Exports by country and region

These results are borne out further by import data, where although Chinese imports slowed down by the end of 2019, they did so by less than imports from Japan (perhaps due to the boycotting of Japanese goods by Korea), and imports from ASEAN were hardly positive, which should not have been substantially affected by the trade war but could reflect more closely the impact of the technology slump.

Korea is not disproportionately exposed to China – something that should help limit supply chain issues in the current virus crisis

To put this into perspective, the Chinese contribution of Korean value-added comes to a bit more than 3.5%. That is not insignificant, but it is less than the China contribution to some other smaller Asian economies, like Vietnam and Cambodia, which are more than 9% and 6% respectively, about the same as Thailand and Taiwan, but almost twice the proportion of value-added of Singapore, the Philippines and Indonesia.

In other words, Korea is not disproportionately exposed to China – something that should help limit supply chain issues in the current virus crisis.

Korean value chain and China

So what about the technology slump?

The technology slump really was a big hit to Korea. With some of the world’s pre-eminent semiconductor and consumer electronics firms, Korean manufacturing was severely hit both by a decline in demand volumes, but also prices for these goods. This has been exacerbated by falling demand globally, but especially in Asia for autos, both an important industry for Korea in its own right, but also a substantial market for semiconductors and other electronic intermediate parts.

The technology slump really was a big hit to Korea

While electronics was the single biggest contributor to production and export growth in Korea in 2017 and 2018, in 2019, it performed the exact opposite role, being a massive drag on both. Happily, towards the end of 2019, this decline looked as if it were coming to an end. And this was reflected not just in export volumes, but also in prices, which also began to stabilise. Autos remain a big drag on Korean export growth, but semiconductors have moved from being a drag to being their principal boost.

Contribution to export growth by item

Sadly, these positive developments all count for virtually nothing, as the Covid-19 outbreak has all but wrecked Korea’s chances of anything but a very poor year in 2020.

Korea’s domestic economy may recover earlier than other parts of the world that are still struggling to contain the Covid outbreak. But the trade balance will be hit by a big swing in domestic demand relative to overseas demand and to global (not just Chinese) demand collapse and supply chain problems.

Even when this disease was predominantly a Chinese problem, supply chain disruptions meant that Korean production was hurt. This inconvenience has been magnified as Korea’s own Covid-19 infection rate has exploded, resulting not just in a hit to demand from households cutting back on consumer services, but outright prevention of household activity as government measures to constrain the spread of the disease have been gradually tightened around the main hotspots.

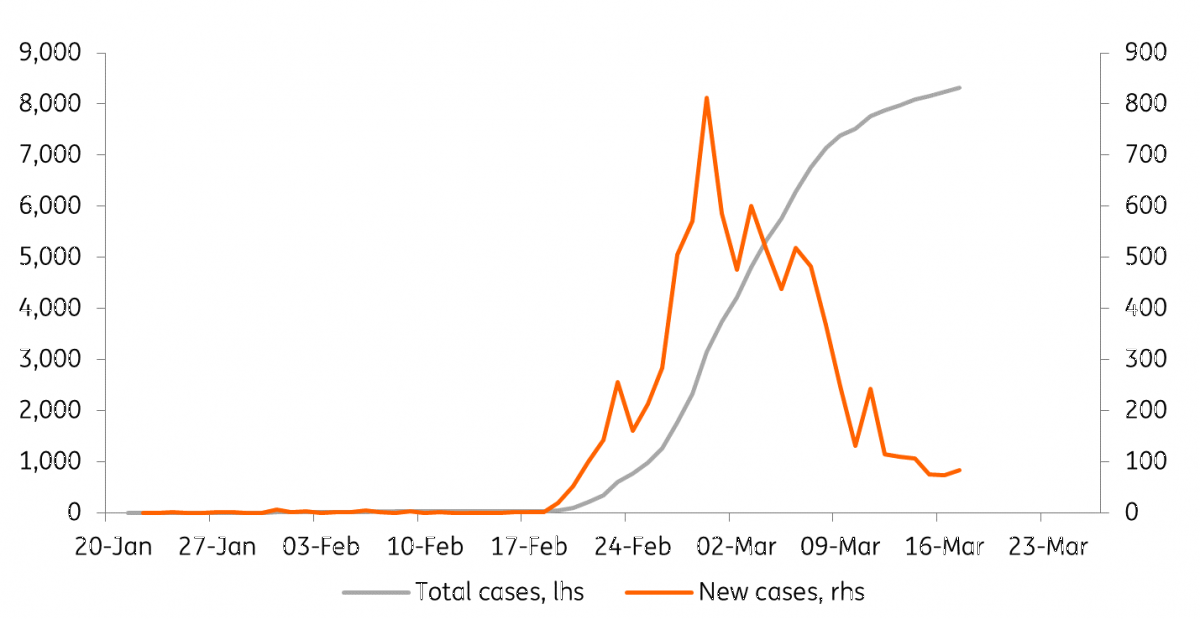

Korea's new and total case count

It looks very much as if these measures are now beginning to pay off, and Korea’s rate of new case increase has begun to tail off.

It remains to be seen how quickly virus constraining measures can be removed, or indeed, how quickly households will return to normal activity. Further questions remain about the extent of collateral damage to corporations, and how much of a problem this is going to generate in terms of bad and non-performing loans for the banking system. The last thing the Korean economy needs is for this outbreak to deliver a permanent loss of output through bankruptcy and the loss of firms and jobs.

The speed with which the outbreak has spread suggests to us that the government will be reluctant to remove containment measures and the public may be reticent in resuming consumption behaviour until they can be sure it is safe to venture back outside.

A number of factors may have predisposed Korea to this outbreak. Here are a few:

- Korea is one of the most popular destinations for Chinese tourists. This is almost certainly how the disease was transferred from China to Korea.

- China is one of the most popular destinations for Korean outbound tourists.

If Covid-19 was not brought over by a Chinese tourist, it was probably unwittingly brought back by a returning Korean tourist.

Korean tourism and China inbound and outbound charts

The good news for Korea is that while this tourism activity probably led them to have one of the worst outbreaks globally after China, as far as the direct GDP impacts go, there is some helpful netting out, and it is also not a large percentage of the economy in either direction.

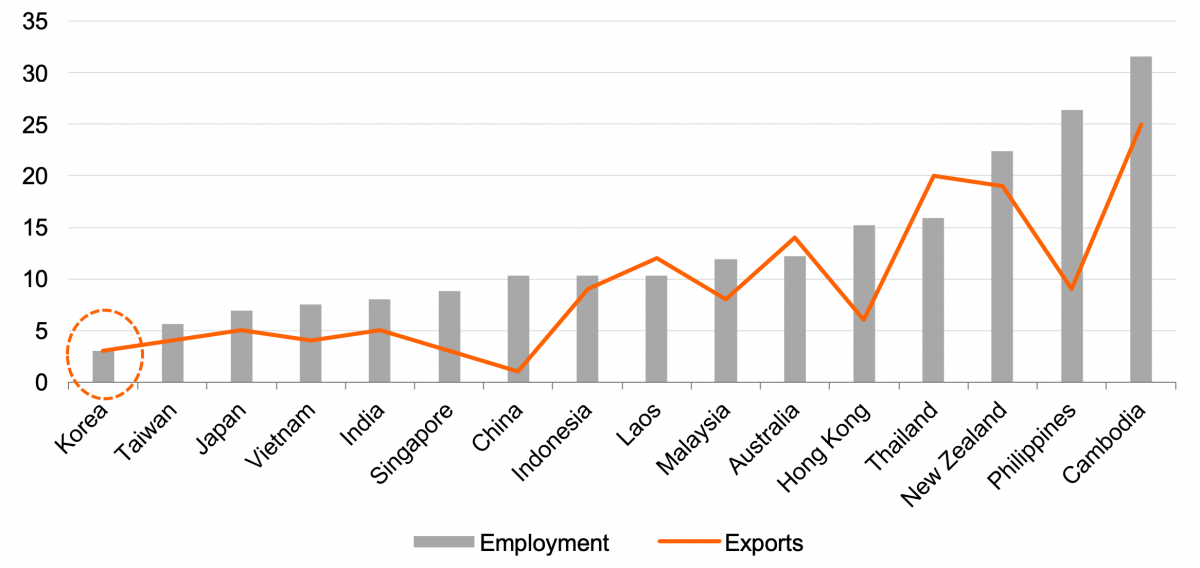

Employment and exports of tourism as % total

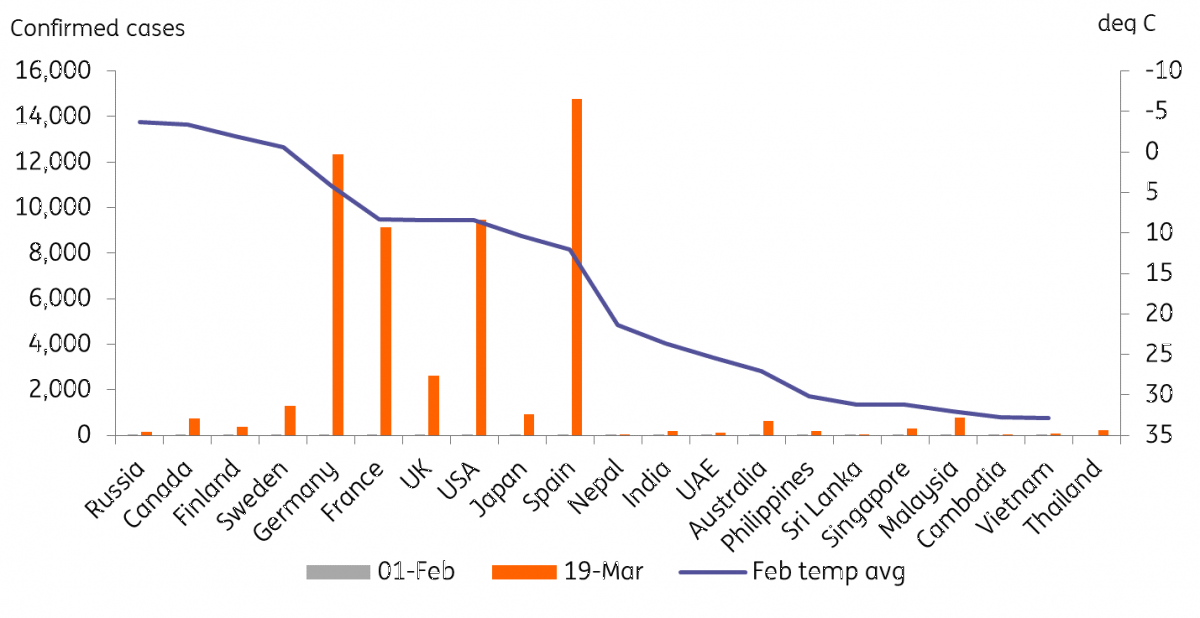

Another reason for some optimism rests on the disease’s resistance to warmer weather. There has been quite a bit of discussion about this, and the scientific community seems to have no strong view on whether Covid-19 will be sensitive to higher temperature and sunlight. That said, since the disease became more globally widespread, it seems to have spread fastest in those countries where the average temperature in February does not rise much above 12 degrees celsius.

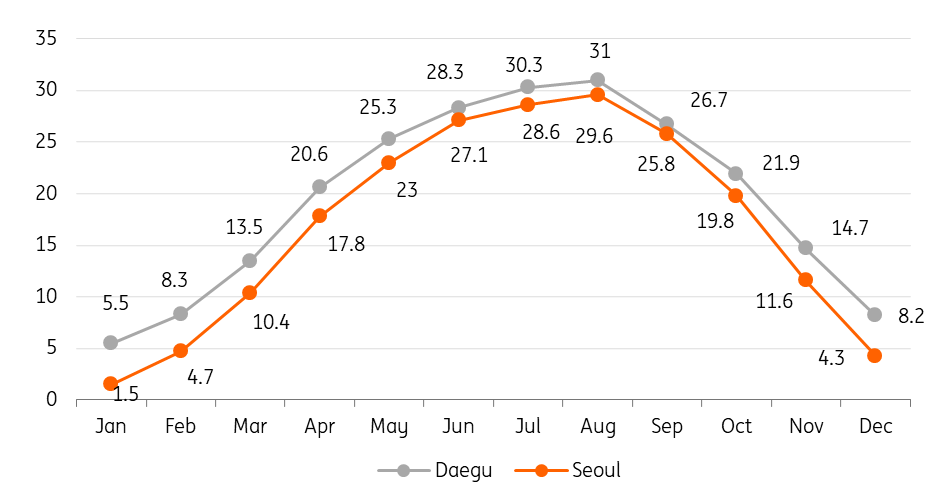

This is true for the city of Daegu at the heart of the Korean outbreak, where average high temperatures for February do not exceed 8.3 degrees Celsius, and Seoul is even lower at 4.7 degrees.

Pushback to this observation tends to come from examinations of cases per capita. In particular, Brunei stands out, though we would note that in absolute terms, the numbers remain small, and related to one infection cluster. The temperature link is perhaps not proven, but it is not destroyed either.

Average temperatures in Daegu and Seoul

We can’t suggest a cut-off temperature at which the virus may cease to thrive if indeed there even is a relationship. But countries with an average high temperature for February of over 20C have typically seen a slower rate of progression of the disease than we have seen in cooler climates. By April, average daily high temperatures in Daegu should rise to above 20C, and Seoul should exceed 20C average highs by May.

While a return to warmer weather is no guarantee of a lower risk of infection, it is maybe not quite as speculative a claim as it looked a month ago, when warmer countries in SE Asia had greater numbers of confirmed Covid-19 cases then Korea. Things have changed a lot since then.

Covid-19 and temperature

Getting Korea’s infection rate under control may enable consumer spending on services to slowly return to normal (forget any notion of V-shaped recoveries though, such services don’t lend themselves well to pent-up demand). However, this may not be so true of the manufacturing industry. Supply chain disruptions have already been seen in China, but Korea should also anticipate similar disruptions from supply chains in Europe and the US, where the outbreak is rapidly spreading, with Italy, France, Spain and Germany virtually shut down.

The Korean government’s response to the Covid-19 infection has been to add a proposed KRW11.7tr supplementary budget on top of a KRW20tr support package to combat Covid-19 on top of an already very expansionary budget for 2020. And now there is talk of yet another supplementary budget on top of all that.

The KRW20tr support package has the following 10 aims:

- Support careful and proper disease control and prevention

- Provide as many as seven million masks for people in Daegu City and Cheongdo County

- Promote the lowering of commercial rents by providing landlords with a 50 percent income tax break for the discount in the first half

- Provide a VAT break for businesses earning 60 million won or less a year

- Help small merchants and SMEs with their business operation: Considerably expand the Special Financial Support for Small Merchant and SMEs

- Provide employment support for businesses hit hard, such as tourism

- Increase the issuance of local gift certificates this year by 3.5 trillion won to help local economies and traditional markets.

- Give parent employees up to five days of childcare leave along with the pay of 50,000 won per day

- Promote consumption: Give a 70 percent individual consumption tax cut for car purchases, and a 10 percent refund for high energy-efficiency home appliances purchases

- Promote consumption by issuing discount coupons to be used for purchasing cultural events and farm products, as well as for tourism expenses and paychecks

The KRW11.7tr supplementary budget includes:

- KRW2.3tr to support disease control;

- KRW2.4tr to help SMEs;

- KRW3.0tr to promote consumption and support job seekers, and;

- KRW0.8tr to help local economies.

Combined, the additional spending and tax/fee reductions announced by the government amount to about 1.7% of GDP in 2019 and provide a reasonably substantial offset against the economic damage caused by the virus outbreak. The scale of this stimulus is perhaps not so surprising viewed against the backdrop of the looming legislative election on April 15 2020. Even so, we see GDP for 2020 coming in at only -0.3%. Given what is going on in the rest of the world, we would not regard that as a bad outcome. But the risk is heavily skewed to the downside.

Korean inflation was very low before the Covid-19 outbreak. To that, we now have to add an oil price war to the weak global demand outlook and oil surplus that looked likely during the first half of 2020. Oil may now remain below $30/bbl for much of the year. As a result, inflation will skirt negative rates over the middle of 2020 on a headline perspective before recovering to a rate of about 1% by 2021.

GDP and Inflation forecasts

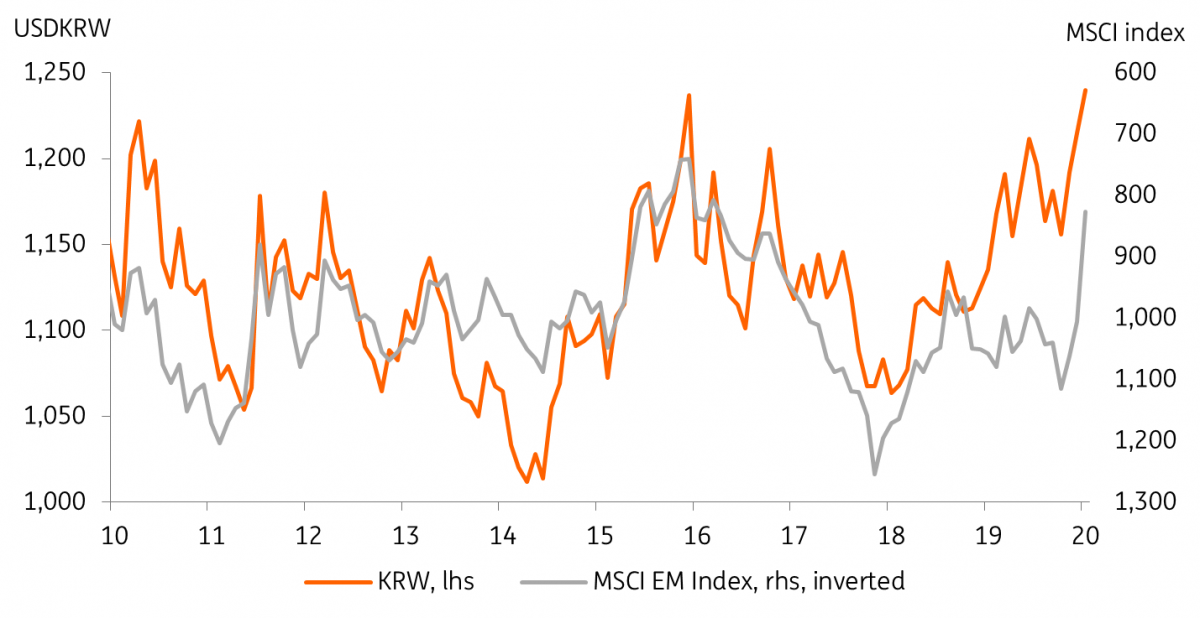

In late February, the Korean won, which had been whacked all the way up to USD/KRW 1220, temporarily appreciated back to an 1180-1200 range as the USD weakened on expectations for Fed rate cuts. But when the cuts came and took US rates all the way down to zero along with a resumption of quantitative easing, they cemented the realisation that the Covid-19 pandemic was dragging the world into a severe recession. As the market has moved into full panic mode, the KRW has sold off again, as investors scurry for the relative safety of the USD.

The KRW is far more sensitive to factors like markets risk aversion (we can proxy this with the MSCI Emerging markets index) than it is to rate differentials or the trade balance. We can easily see 1300 in the coming weeks if panic grips markets again once it realises that central banks have used up what little ammunition they had.

KRW litmus for market anxiety

There could be some KRW recovery as US Covid-19 cases accelerate. The US is a late mover in the Covid crisis, whilst Korea seems well on the way to containment. However, for now, that seems too finessed a view for the market to take on board, and the KRW is being sold like every other currency, only more so.

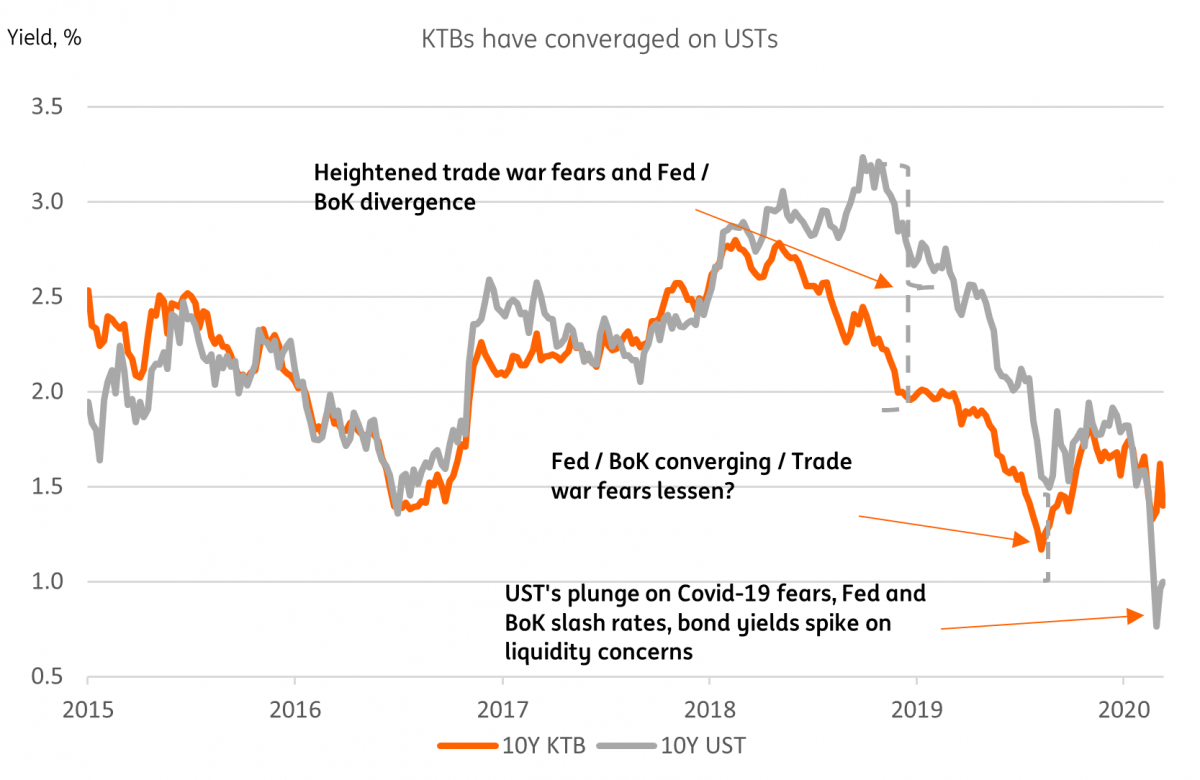

Korean Government bond yields have broadly tracked US Treasuries, with the spread fluctuations between 10Y securities roughly tracking the relative movement in policy rates in the two countries. 10Y KTB's yield about 40bp more than their equivalent US Treasury bonds currently, while the spread is a little wider at the level of policy rate But we don't think that will persist for long.

Right now, both US Treasuries and KTBs are being sold and yields are consequently rising as the demands for cash, and in particular, US dollars soars. If the Fed is successful in restoring market liquidity and calm returns, we may see yields on both KTBs and Treasuries decline. This would represent a slightly counterintuitive improvement in expectations.

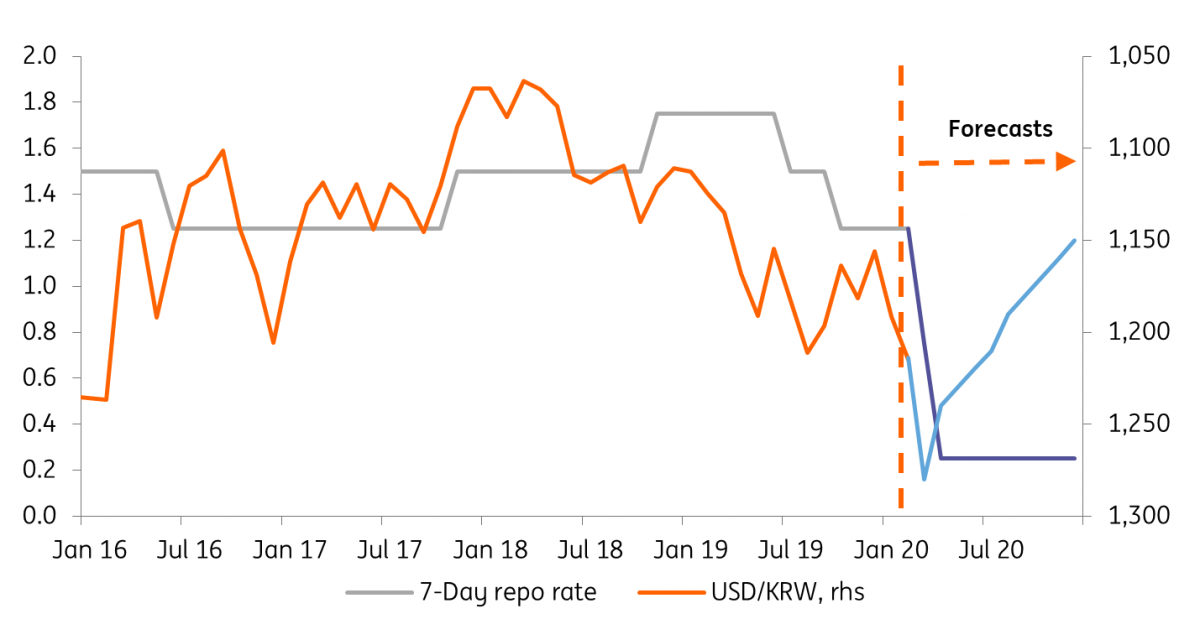

KTB Treasury

The market was divided over whether the Bank of Korea (BoK) would cut rates in February, and in the end, they did not. But the aggressive easing elsewhere in the region, together with the Federal Reserve slashing rates to virtually zero and starting QE, has made it very much easier for the BoK to play catch up in March. The 50bp of easing on 16 March, taking the 7-day repo rate down to 0.75% was unusually aggressive for this reticent and usually hawkish institution.

The threat of permanent output loss from inaction suggests to us that we will see a further 50bp of easing at the April meeting

Right now though, I think they and other central banks are realising that there is little to be gained from timid policy moves, and the threat of permanent output loss from inaction suggests to us that we will see a further 50bp of easing at the April meeting. It isn’t an impediment that there is a legislative election coming up shortly after, so the government, for once, won’t be wanting the BoK to sit on their hands.

One argument against more easing might once have been the government and BoK’s pre-occupation with household debt levels

KRW and official rates

There is a perception that Korea, and in particular, the Korean household sector, is heavily indebted, and that lower interest rates will simply encourage more borrowing, storing up problems for the future.

We don’t accept this hypothesis.

Despite media suggestions, there is little evidence that Korea’s property market is in a bubble

Yes, as a proportion of household incomes, household debt is high. The household debt ratio, depending on sources, is anything between 140-160% of household incomes. That is fairly high by international standards. For example, it is comparable to the US household sector debt pre-sub-prime crisis. Like the US household sector then, Korea’s households are also heavily invested in property. This has been a strongly performing asset, and as a result, the ratio of total household liabilities to assets is low and has not trended in any meaningful way over the last decade. Moreover, despite media suggestions, there is little evidence that Korea’s property market is in a bubble.

Solvency is probably a better metric for households than a simple debt to income or debt service ratio measure. And when you compare the ratio of household sector short-term liabilities to liquid assets, the picture that emerges is not only very low but also very stable.

Korean balance sheet data

The non-financial corporate sector also looks similarly unthreatening when flow-of-funds data are used to examine its balance sheet stock ratios. Total liabilities to assets have fallen over the last decade, as have short-term liabilities to liquid assets, of which they are a very small fraction. Even the degree of cross-shareholding seems to have decreased, which lowers systemic risks.

The outlook ahead

Korea faces a miserable year, though not of its own making. The authorities have done a good job of containing and limiting the impact of the coronavirus, and though work remains to be done, Korea seems to be in a better place than some European countries, and possibly before too long, the US. But it will be scant consolation to control Covid-19 if the rest of the world is in recession, and for all intents and purposes, 2020 should be regarded as a year of economic survival, and nothing more.

In summary, Korea faces a miserable year, though not of its own making

The forecast numbers are provided below for completeness, but until 2021, they have very little meaning other than to note that activity is very weak, pricing power virtually absent, and market prices similarly soft. Underlying all this is a genuinely improved structural backdrop. But without knowing exactly how much permanent and collateral damage this coronavirus wreaks, 2021 forecasts are really subject to far more uncertainty than is usual at this point in the calendar year and we would advise against reading much into any of these numbers.

Summary table

Download

Download article

23 March 2020

Good MornING Asia - 23 March 2020 This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more