Is REPowerEU too focused on renewables as a way to cut out Russian gas?

The European Commission has rolled out its plan to reduce gas dependence on Russia. Renewables get too much attention considering their limited potential to replace gas for heating purposes

The European Commission's so-called REPowerEU plan aims to cut out 100 billion cubic metres (bcm) of Russian gas imports – worth roughly two-thirds of total imports from Russia – by the end of this year. From a short-term economic perspective, the Commission's emergency measures on energy prices are the most important. These are the four key takeaways from an energy system perspective:

Liquefied natural gas will need to do most of the work

What the Commission has in mind is to cut out 100 bcm of Russian natural gas from its imports. The EU imported 155 bcm of natural gas from Russia in 2021 through pipelines, a level that has remained consistent in the last five years, ranging from 152 to 166 bcm.

REPowerEU focusses on replacing Russian gas with non-Russian gas supplies of 60 bcm, most of which would come from increasing liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports. Such an objective seems very challenging, given current European import capacity and the cost at which this would be done.

The plan targets another 20 bcm to come from front-loaded wind and solar renewables adoption, to replace gas use in the power sector.

Energy savings in buildings, like turning the thermostat down, could save another 14 bcm, something the International Energy Agency also recommended.

Other measures such as front-loaded biogas adoption, green hydrogen uptake, and heat pump installation could also support the transition out of Russian gas. But the potential of these is very limited in the short term.

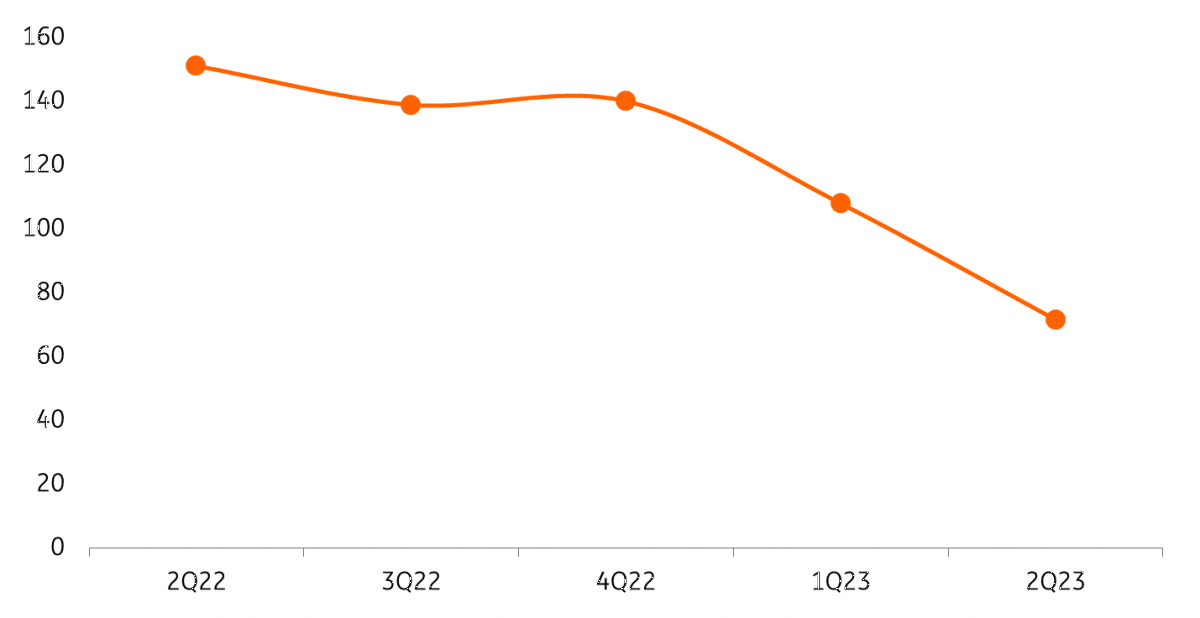

REPowerEU proposes to reduce Russian natural gas imports by two-thirds this year (100bn cubic meter)

Alternative solutions to Russian natural gas pipeline flows, in billion cubic meter (bcm)

The numbers show no lack of ambition, although it remains to be seen how much of the Commission’s proposal will be rubber-stamped at the two-day EU summit in Versailles this week.

Short term climate pain, versus long-run gain

Assuming the EU wants to almost fully reduce its Russian gas dependence (by 80%), it would mean an additional 30 bcm from the gas-to-coal switch. The plan doesn’t mention explicitly gas-to-coal switches or carbon capture and storage (CCS) solutions to reduce the carbon footprint of fossil fuels, but Frans Timmermans, the Commission’s vice president for the European Green Deal, mentioned a few days ago that countries could do this in line with 2030 climate goals.

Germany is already reactivating coal-fired power plants as it is reluctant to prolong its remaining nuclear reactors. This bodes badly for European greenhouse gases in the short run. The recent drop in the EU carbon price only adds to that.

On the other hand, note that REPowerEU comes on top of climate change policies the EU is currently negotiating with the Fit for 55 package, which is designed to cut emissions faster this decade. REPowerEU is a step up from what the Fit for 55 package intended and confirms that climate ambitions and energy security are not incompatible.

Full implementation of Fit for 55 would already reduce the EU’s annual fossil gas consumption by 30%, equivalent to 100 bcm by 2030. REPowerEU would increase that figure up to 155 bcm by 2030.

The current market needs mandatory filling targets for gas storage facilities

Europe’s gas storage facilities play a pivotal role in providing energy security throughout the winter in which gas use is highest and highly dependent on weather conditions. Currently, after a relatively mild winter, gas reserves are filled by around 30%. Reserves stood at just 20% after the cold winter of 2018.

Now that the heating season is almost over, the priority is all about filling up gas storages throughout the summer to prepare for next winter. In April, the Commission wants to present legislation that requires underground gas storage capacity to be filled every year to at least 90% by 1 October. Some countries already have such legislation in place, like France, whilst others, like the Netherlands, don't.

The proposal therefore ends the dilemma for gas operators, who have to choose between filling gas reserves this summer, at a very high cost, or waiting for gas prices to fall, risking the security of supply again next winter.

The forward gas curve currently provides no economic incentive to replenish reserves as prices are expected to be higher in the spring and summer (buying season) and lower during the winter (selling season). Hence, the current market needs mandatory filling targets, although they come at high costs.

The TTF forward gas curve highlights the dilemma of gas operator

In euros/MWh

REHeatingEU would have been a better name

To support the communication of the EU’s energy resiliency, Timmermans suggested we “dash into renewable energy at lightning speed”. That is also indicated by the name of the plan, REPowerEU, as renewables are good at producing power from solar and wind energy.

But renewables do a poor job at producing heat to keep our buildings comfortable and to run high-temperature processes in manufacturing. And that’s what Europe needs half of its energy for. This heating demand is predominantly generated by gas and coal use. Only a fifth of Europe’s energy stems from power generation, and there gas is only one of the many energy sources that can be used.

So, reducing Europe’s gas dependency on Russia has everything to do with heating demand, and far less with power demand. While it is common practice to frame the energy transition in terms of solar and wind power, the potential to reduce Russian gas demand is limited. The focus should be firmly on gas supply and demand for heating purposes. That’s why REHeatingEU would have been a better name.

Gas is mostly used for heating purposes in buildings and manufacturing processes

Total energy consumption in Europe per energy use in 2019

Europe is still far from being self-sufficient in energy production and is still largely dependent on its imports. The Russian-Ukraine crisis has sped up the process to phase out fossil fuels and to become less dependent on Russian gas. But replacing two-thirds of imported Russian gas in fewer than 10 months is not only a technical challenge. It will also result in a substantial cost for all energy consumers. The success of the plan will ultimately depend on two factors: on the one hand, the political will to take investment and regulatory decisions in a very short amount of time, and on the other, the ability of energy consumers to pay their energy bills and moderate their gas consumption.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article

10 March 2022

A global power struggle This bundle contains 9 Articles