India is sticking with coal

India's adoption of a 'strategically neutral' position with respect to the Russian invasion of Ukraine has seen it buying more cheap Russian oil, gas, and coal. In the face of energy shortages, India is also investing more in coal, even as it expands its renewables capacity

Where does it want to be?

India, the world’s third-largest emitter of carbon dioxide, pledged at the COP26 summit in November 2021 to achieve net-zero carbon by 2070, 20 years later than scientists agree is necessary to meet climate change targets

What it has been doing to get there:

At the last climate summit in Glasgow, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced enhanced climate targets for India:

- India will reach its non-fossil energy capacity of 500 GW by 2030.

- India will meet 50% of its energy requirements from renewable energy by 2030.

- India will reduce the total projected carbon emissions by one billion tonnes from now until 2030.

- By 2030, India will reduce the carbon intensity of its economy by less than 45%.

- By the year 2070, India will achieve the target of net zero.

But despite these pledges, observers believe that India is already falling well behind on its delivery of renewables capacity. India has an ambitious 2022 renewable energy capacity target of 175 GW. As of July 2021, it had installed less than 100 GW and is now unlikely to reach the target.

A World Economic Forum White Paper suggests that the transition to net-zero by 2070 will cost India $15tr. But to get there, the government will need to set clear targets and roadmaps for each sector, a framework of regulations and incentives to catalyse change and innovation, take a balanced approach to carbon pricing, and a collaborative process for stakeholder engagement. The implication of these requirements is that these measures have not yet been implemented.

What's happened since the Ukraine war?

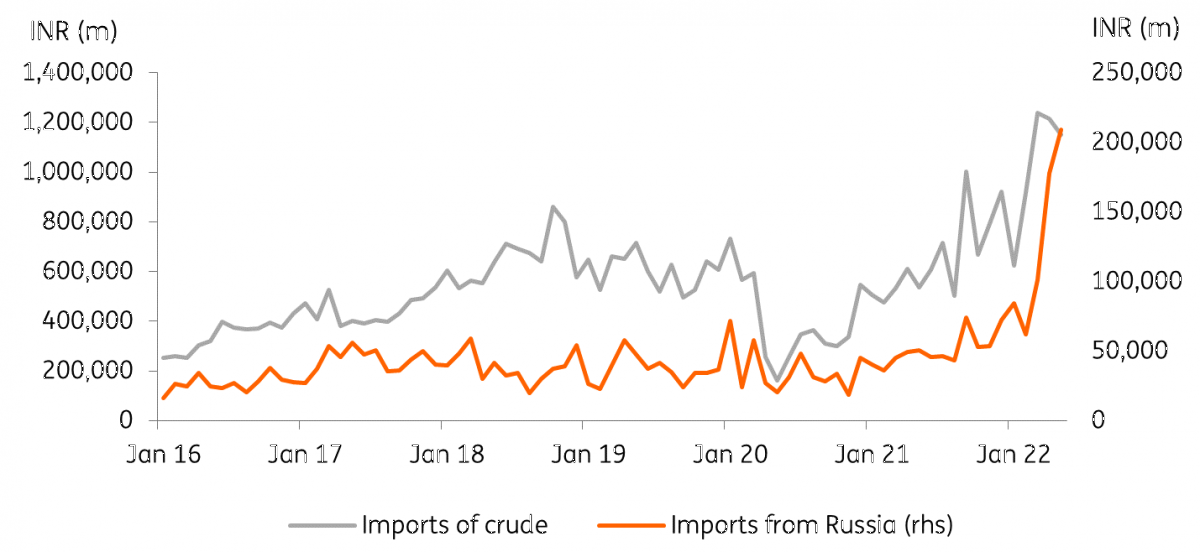

India’s import volumes of crude oil and coal have surged since February. Compared to pre-pandemic levels, imports of coal and petroleum are respectively 359% and 607% above their pandemic lows. Much of this is coming from Russia. Imports from Russia have risen from a low of INR20.2m in May 2020, to INR208.9m in May 2022, approximately a tenfold increase in Indian rupee (INR) terms, and in volume terms probably larger as Russian prices are heavily discounted.

The purchases from Russia have been made through privately negotiated deals by state-run processors, which have bought cheap Urals grades of oil, ESPO cargoes and even Sokol grades usually destined for China.

Despite this, record temperatures, economic re-opening and a shortage of railway wagons for transporting coal – the fuel used for 70% of India’s electricity generation – have in recent months led to power outages as surging demand has met faltering supply. So far, this has not spurred an acceleration in the transition to renewables.

Indian imports of crude, and imports from Russia

India turns to coal imports to solve energy shortage

In contrast to some economies, which are using the Ukraine war as an opportunity to push harder to decarbonise, India is using the opportunity to fund its existing (even growing) fossil fuel appetite at a beneficial rate. India is now the biggest single purchaser of the Russian Urals grade of crude oil, in spite of warnings from the US not to buy greater than normal amounts of Russian oil.

India has also been buying Russian coal. With Russian coal trading at about a $60-65 discount to Newcastle coal, this is low enough to offset the increased freight costs.

India’s medium-term coal ambition is not to phase it out, but to phase out imports, becoming self-sufficient in production. But on 5 May, India’s Ministry of Power asked state governments to import more coal. It also ordered coal-fired power generators to run at full capacity until 31 October, invoking the Electricity Act.

The Ministry for Energy said that although the supply of domestic coal had increased, it was not sufficient to meet the increased power needs. And this was why the country was turning to coal imports.

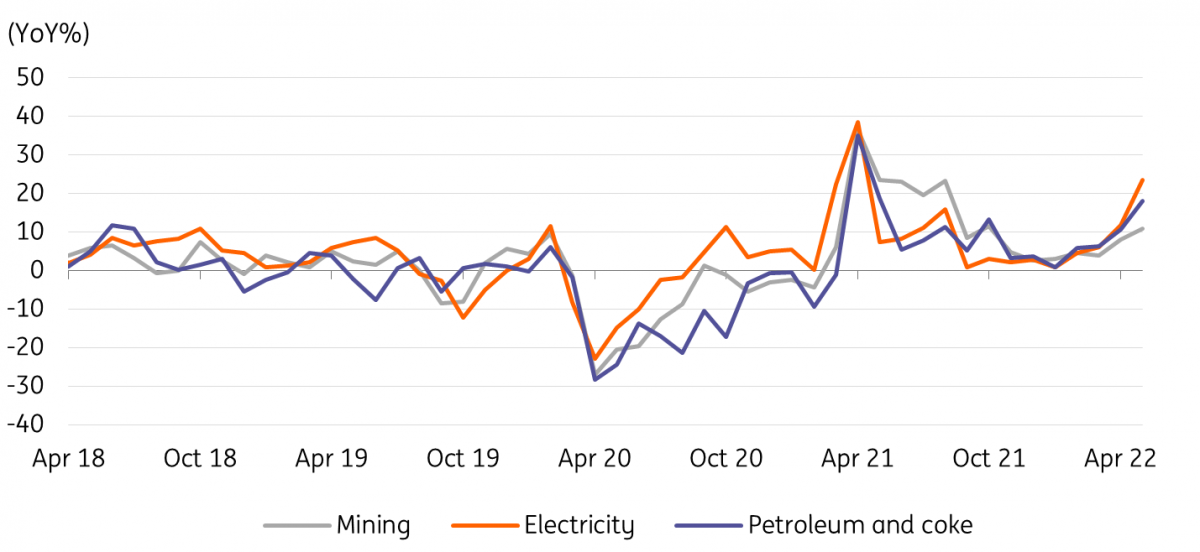

At the same time, the Coal Ministry announced that India would boost domestic coal production to 1.2 billion mt in fiscal 2023-24 from 777 million mt in fiscal 2021-22, partly by reopening closed mines. In June, India’s coal production increased by 32.57% to 67.59 million tonnes. Coal-fired electricity generation declined slightly in June as the arrival of Monsoon rains dampened demand.

The Coal Ministry’s intention to increase coal supply follows falling coal stocks after high energy demand during intense heatwaves earlier in the year depleted stockpiles and following high international prices that discouraged imports. This resulted in power rationing in a number of states affecting industrial, residential and agricultural users.

There has also been a shift back to coal-fired energy generation in India in response to recent power shortages. In May, NTPC, India's largest electricity supplier, was reported to be about to award a contract for a 1.32MW coal-fired plant in Odisha in eastern India. If this goes ahead, it would be state-owned NTPC's first coal expansion project in six years. The same report also indicated that NTPC might seek to revive two stalled projects in Lara and Singrauli.

It isn’t all negative news though. In June, NTPC also commissioned India’s largest floating solar project – a 100MW plant spread over 500 acres of an NTCP reservoir at Ramagundam.

India's mining output, electricity, petroleum & coke

Summary

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine looks to have led to backsliding in India’s already unambitious plans to achieve net-zero carbon by 2070. Increased purchases of Russian oil, gas and coal combined with greater domestic production and fossil-fuelled energy generation, especially coal, are clear evidence that India is moving further away from its earlier pledges on decarbonisation.

It is ironic that the heatwaves that have been striking India and leading to increased demand for fossil-fueled electricity generation, are most likely a side-effect of fossil-fuel-induced global warming. This is not the only instance in the region where extreme weather events which may result from global warming have led to a worsening, rather than improvement in fossil fuel emissions (see also: Australia note).

In addition, the relatively young age of India’s coal-fired generating capacity suggests that this will be part of India's baseline generating capacity for decades to come. However, it is worth noting that not all additional capacity is coming from fossil fuels, with significant additional capacity from renewables also being added.

Download

Download article

1 August 2022

How the Ukraine war has affected Asia’s race to net zero This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more