How the ECB’s rate hikes are filtering through to the eurozone economy

The European Central Bank's policy stance has become restrictive. To us, the impact on the economy is probably the most underestimated drag on growth for 2023. The good news is that we see no meaningful signs of fragmentation between countries, so monetary policy is not causing shocks in more vulnerable parts of the eurozone

Last summer, when the ECB started hiking interest rates, the immediate question for financial markets was how far the Bank would dare to go. Ending an era of negative interest rates and unconventional monetary policy when inflation is approaching double-digit levels is one thing, actively breaking down the economy is, however, another. This is why the eurozone's nominal neutral interest rate – which was pegged at between 1.5% and 2% by almost everyone – suddenly became the focus of attention. Even ECB President Christine Lagarde referred to this illustrious neutral rate (the rate at which monetary policy neither stimulates nor restricts the economy), suggesting that the central bank use this as a rough anchor for when policy could start to become restrictive. When policy is restrictive, this leads to weakening economic activity and ultimately to lower inflation. The rate, however, is a very theoretical concept, impossible to measure and rather an ex-post instrument to describe a monetary policy stance rather than providing guidance for actually conducting monetary policy. This is why the ECB quickly, at least publicly, debunked the idea that it would follow this neutral interest rate concept. Wherever a neutral interest rate in the eurozone might be, hiking interest rates by 300bp, as the ECB has done so far, and with more hikes to come, the question is not whether the ECB’s hiking cycle will slow the eurozone economy but rather when.

Most channels through which higher rates work are showing tightening impact

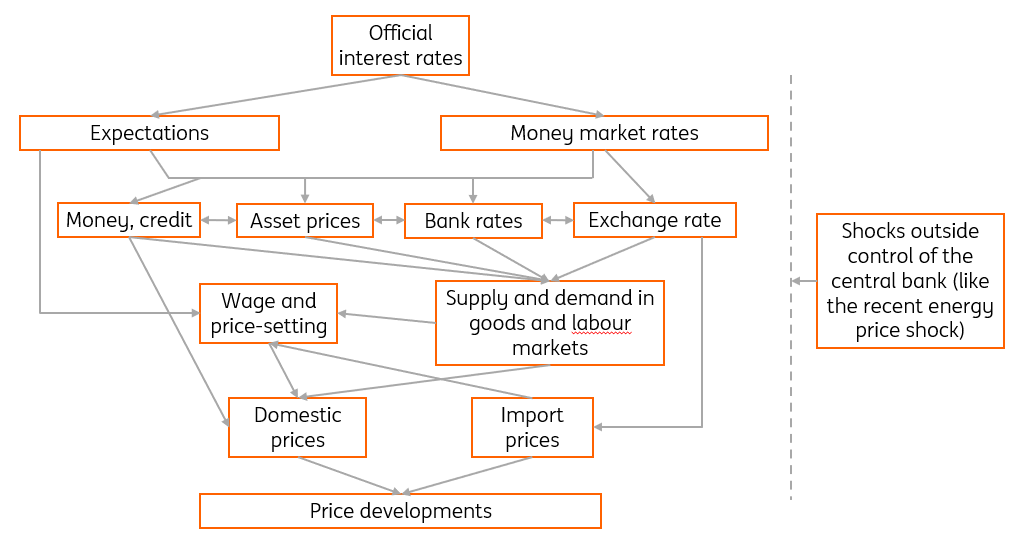

Let’s use the ECB's own handy flowchart to explain how it sees monetary policy ultimately feeding through to prices (for the ECB’s own assessment, we can recommend Chief Economist Philip Lane’s speech from 16 February). The four main transmission channels are: money/credit, asset prices, bank rates and the exchange rate. All four channels have seen sizable adjustments since last summer:

ECB’s own take on monetary transmission

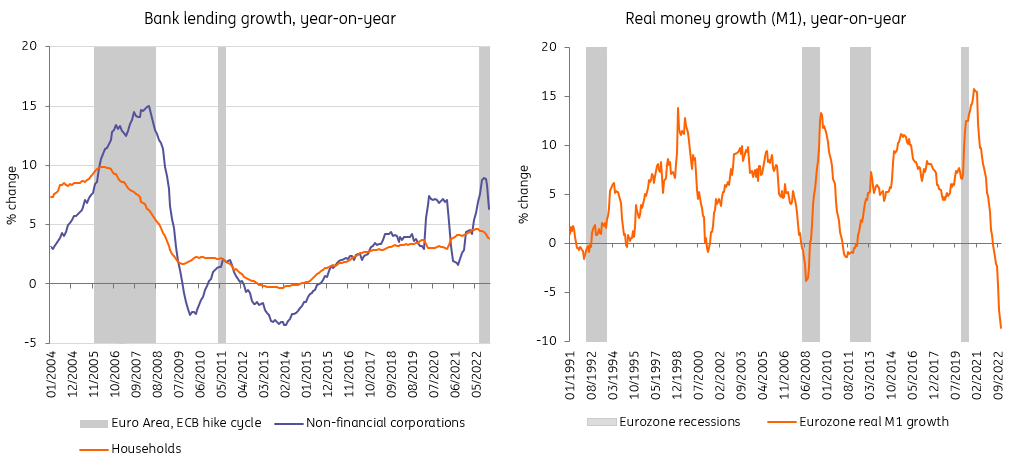

- The money supply has fallen quickly since the ECB started reducing asset purchases. In fact, growth in real money (M1) has not been so negative since the ECB's record-keeping began. This historically corresponds with a significant correction in economic activity.

- When looking at asset prices, we see that stocks and bonds saw a significant correction in 2022 (although we have seen a rebound in prices as expectations of a peak in policy rates have grown this year). Real estate prices are somewhat slower to respond but are undoubtedly starting to turn. In countries like Germany and the Netherlands, price declines have already become somewhat sizable as the combination of higher bank rates, low consumer confidence and lower purchasing power is resulting in declining housing demand. This is not where it will stop. We expect this to have an impact on construction activity in the coming year.

- Bank rates have also considerably increased since the beginning of 2022, following the increase at the longer end of the yield curve. This is starting to curb investment as growth in bank lending has almost stalled for households and is considerably negative for businesses. Traditionally, business borrowing reacts with longer lags to higher rates than consumer borrowing. Last year, for example, borrowing by non-financial corporates held up until mid-2022 because of working capital needs – due to supply chain problems for example. Recently, however, there has been a sharp correction, which has been much quicker than in previous cycles. That correction corresponds to the Bank Lending Survey, which indicates that borrowing needs for investment reasons have fallen significantly in recent months. We expect this to have an important dampening impact on investment in the eurozone in the quarters ahead, although the recovery fund's impact on southern economies could mute the overall investment response seen in 2023.

- The euro has appreciated since the end of last year as investors are expecting more rate hikes from the ECB and because energy prices have fallen significantly from the peak which has resulted in a smaller trade deficit. This is starting to feed through to import prices, which have started to see lower year-on-year growth. In fairness, the bulk of that move down has resulted from the lower energy prices seen recently, but the impact of a stronger euro will be felt down the line.

The early phase of monetary transmission is fast at work

No need for TPI as monetary transmission is not showing signs of fragmentation

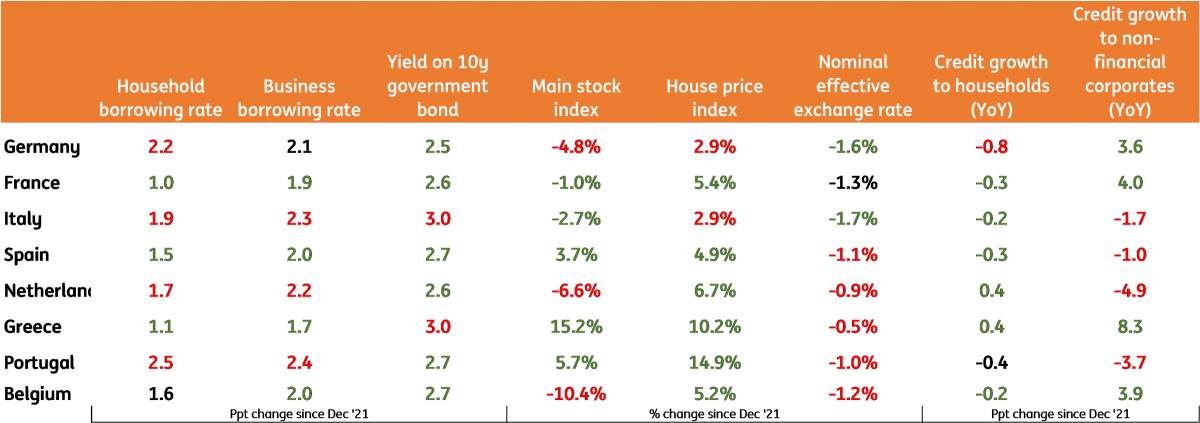

When looking at the above-defined categories per country, we see that there is not that much difference in transmission. The rise in percentage points for borrowing rates differs just modestly between countries and the nominal effective exchange rate has made roughly similar movements for most countries – as expected.

Liquid assets have seen declines across the board, with a few stock markets in Southern Europe notably outperforming. House prices are still well above levels seen in late 2021, although Germany and the Netherlands are starting to see a correction as a downward trend has started which the table below does not pick up on.

The money supply is of course handled centrally, but recent developments in bank lending can say something about credit reaching the real economy. Here, we see the most striking difference so far, as Italy and Spain have seen declines in borrowing from non-financial corporates, whereas Germany and France have not, yet. The important caveat here is that we have seen quite some borrowing for working capital and inventory reasons, which has driven up borrowing or at least made borrowing more volatile. For Germany, the bank lending survey suggests declining demand for investment borrowing, which means that transmission could be at work more than the numbers suggest.

Compared to the average, we see that France is the country still experiencing a smaller impact on all counts, while Italy is experiencing a somewhat more significant impact. Overall though, there is no shock happening in the system for any country measured, and monetary transmission is therefore not causing problems. So far, there is no reason to use the ECB’s new Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI) as fragmentation of monetary transmission in the eurozone is not happening at the moment.

The much feared fragmentation of monetary transmission has not happened so far

Most of the impact on inflation and growth still has to feed through

While the initial boxes of monetary transmission have clearly been ticked, the timing of the actual impact of monetary policy on the real economy has always been difficult. In theory or in large macro models, it is assumed that it takes 9 to 12 months before monetary policy affects the real economy most. Recently, there have been central bankers (Fed members) suggesting that the lag could currently be shorter than in the past.

In any case, the transmission of monetary policy can often be blurred by other factors. At the current juncture, the energy crisis is playing a large role in slowing down the economy and has also helped to ease inflation as recent developments have caused gas and electricity prices to come off their peaks. Supply chain problems have been fading recently and demand for goods has weakened, which has helped supply and demand in goods markets become better balanced again.

How does this stack up to previous hiking cycles?

It is difficult to compare current developments to previous tightening cycles by the ECB. The ECB has only engaged in three previous hiking cycles, of which the 2011 one only lasted for two meetings. The thing that stands out is that the underlying conditions of the economy matter a lot when looking at the pace of transmission. The 2005 hiking cycle happened when the economy was performing quite well, the 2000 cycle started in a strong economy, while 2011 was a famous example of hiking into a recession.

That difference shows when looking at the response. In 2005, bank lending growth to businesses continued to accelerate despite rate hikes and only slowed when the 2008 recession started. We now see a much faster response. Asset prices are now also turning down much faster than in 2005 as this only happened years after the start of the tightening cycle in 2008, while we are already seeing the negative effects now. This also holds true for money growth. So while we have little to compare to, it does become evident that the key channels of monetary transmission are seeing faster downturns now than in the previous long tightening cycle of 2005.

But it’s too early for the ECB to declare victory yet

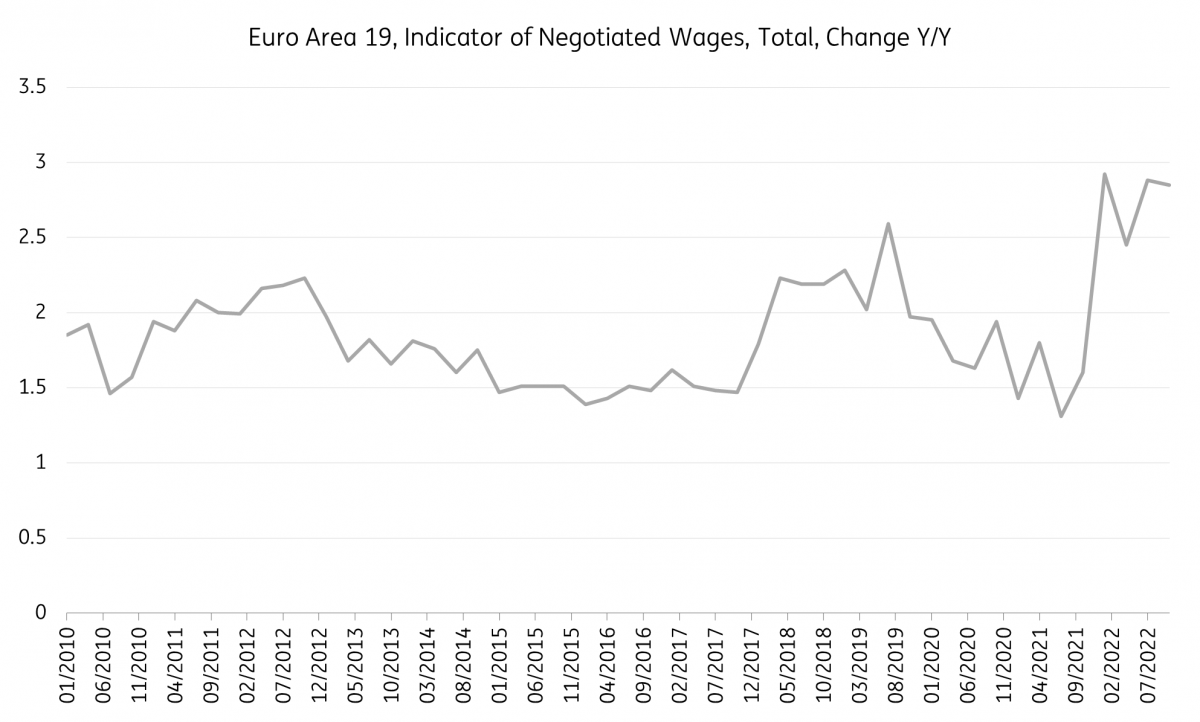

While inflation is falling, core inflation is still trending up and is far above target at 5.2%. It is therefore too early to declare victory on price developments. Wage growth is also still moving up cautiously. While not nearly enough to raise concerns about a wage-price spiral, the labour market remains red hot and negotiated wage growth has moved from the 1.5% to 3% range in 2022. So supply and demand in labour markets have yet to adjust.

Wage growth has started to trend up, causing upside risk to the inflation outlook

And expectations have started to feed through the monetary transmission system in the wrong way recently. As investors worry about recession and are optimistic about inflation returning to benign levels, we see that financial conditions are loosening again. This could work against tightening efforts from the ECB and we have seen ECB speakers speak out quite vocally against the premature easing of financial conditions.

A lot is now moving in the right direction for the ECB to get inflation back to target, but uncertainty remains. No one really knows how persistent core inflation will be after this series of supply shocks that the eurozone has faced. There is also uncertainty over how long it will take for GDP and inflation to be impacted by the aggressive rate hikes from the ECB so far. Having moved to a restrictive level of policy recently and with more hikes in the pipeline, this uncertainty makes policy-making very difficult right now.

Restrictive policy will have a significant downside impact on the economy this year

While we are not seeing the full impact of monetary policy on prices yet, we do see transmission in full force, which will eventually have a larger impact on output and prices. With uncertain delays on economic activity and prices at work, the question is how hawkish the ECB will remain over the course of the year, given the tightening of monetary policy so far. At the March meeting, another 50bp hike is all but a done deal. Beyond the March meeting, however, the ECB will likely be entering a new phase in which further rate hikes will not necessarily get the same support from the Governing Council, as hiking deep into restrictive territory increases the risk of adverse effects on the economy. The main question beyond the March meeting will be whether the ECB will wait to see the impact of its tightening on the economy or whether it will continue hiking until core inflation starts to substantially come down. In the former case, the ECB could consider a pause in its tightening cycle and hike again at the June meeting. The latter would see continuous meeting-by-meeting hikes, possibly in smaller increments of 25bp.

For our economic outlook, we think that restrictive monetary policy in 2023 will be a key factor preventing the economy from bouncing back from its current weak spell. While all eyes are on the energy crisis at the moment, higher rates will also be an important factor in dampening any meaningful recovery. While we don’t see the bulk of the impact yet, expect a eurozone economy that flirts with zero growth for most of the year as higher rates complete the transmission to demand.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more