French elections: A Macron-Le Pen rematch is far from guaranteed

With around 200 days to go before the French presidential election, just what's at stake? Who could win? And, in reality, will the outcome really be any different to what we saw in 2017?

And so the presidential campaign begins. With the recent entry of Anne Hidalgo in the campaign for the Socialist nomination and the first campaign speech of Marine Le Pen, the race for the presidential ticket is on. The first round is on Sunday 10 April and the second, two weeks later, on 24 April.

With more than 20 declared candidates, the French political horizon is still very blurred. And that’s the least one can say since the last regional elections in June 2021 put a stop to the reconfiguration of the political landscape which began in 2017. Neither Emmanuel Macron's La République en Marche party nor Marine Le Pen's Rassemblement National achieved their goals in the regional elections and we also got a record abstention rate. The results of the Green primary in mid-September, and the results of the Les Républicains party's major consultation to determine how to designate a single candidate on the right, should provide more clarity on the candidates in the running.

Purchasing power and wage increases will be at the heart of the campaign

But in terms of economic themes, the major issues are now clearly emerging. The question of purchasing power and wage increases will be at the heart of the campaign, as will proposals for environmental transition, with parties which have traditionally overlooked the subject, such as the Rassemblement National, now beginning to take it on board. With Covid-19 having revealed the country's dependence on foreign suppliers in certain strategic sectors, we can also expect a surge of proposals in favour of reindustrialisation and national sovereignty. Despite the "whatever the cost" approach used during the Covid crisis, no candidate has yet spoken out about controlling public finances, whereas this was a dominant issue during the previous presidential campaign in 2017.

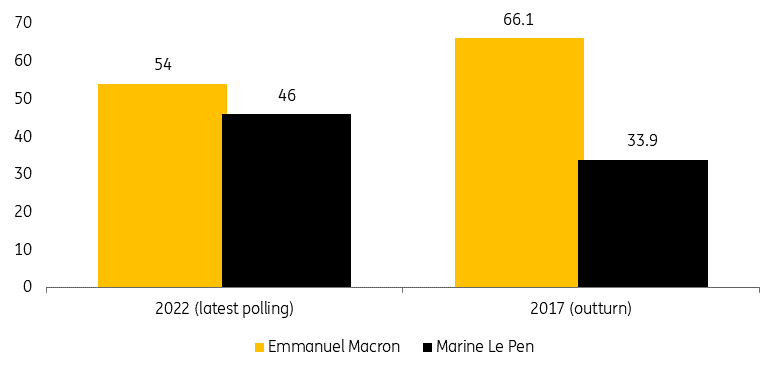

All polls currently indicate a rematch of the 2017 Macron-Le Pen duel in the second round of elections with a Macron victory. But if there is one lesson to be learned from French politics, it is that presidential elections always hold their fair share of surprises. The story of François Fillon, candidate of the right in 2017, who was positioned as a favourite to win and collapsed at the end of the campaign amid an employment scandal involving his wife, is a perfect illustration that anything can happen in a French presidential campaign. As a reminder, in 2017, this incident led to Fillon's downfall in the first round and ultimately to Emmanuel Macron's victory.

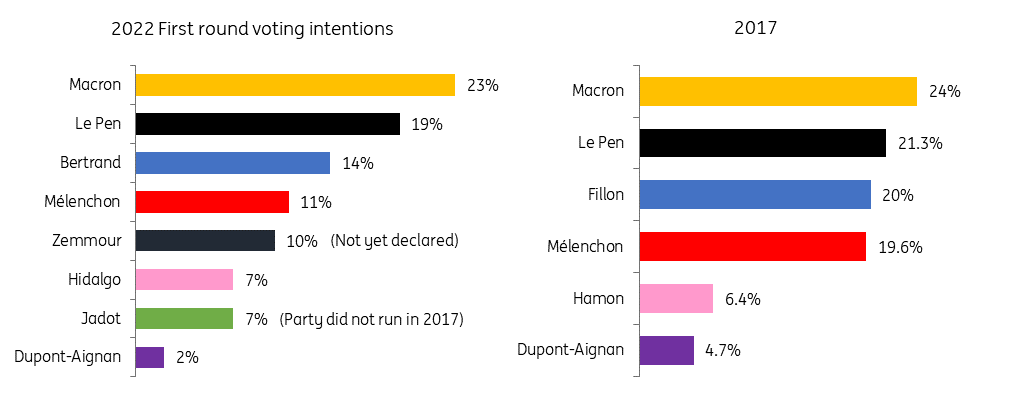

France presidential election first round (%)

Emmanuel Macron, renewing the renewal

Emmanuel Macron has not yet announced his candidacy for the 2022 presidential elections, but there is not much doubt about it. Although a televised speech on 12 July sounded like a campaign address, he is currently more comfortable as president than a candidate against a backdrop of high popularity ratings, a pandemic that is globally under control thanks to the success of the vaccination campaign and a stronger than expected economic recovery. By all accounts, Emmanuel Macron seems willing to defend his results, notably by highlighting the positive impact of the recovery plan. He also continues to highlight themes favoured by the right: championing the self-employed and the security and implementation of unemployment insurance reform. This is because, according to current polls, only a right-wing candidate would be able to win against Emmanuel Macron in the second round.

Macron might be tempted to launch initiatives before his term ends to show that he is indeed still a reformer

The support of Edouard Philippe, the president's prime minister for three years and a strong man of the right, can be considered an important element in rallying right-wing voters. In the short term, the unknown lies in the issue of pension reform. Macron might be tempted to launch reforms before the end of his five-year term to show that he is indeed still a reformer. However, this issue is potentially inflammatory and, if badly negotiated, could ultimately harm him. All the more so as France has just gone through a turbulent month of August, marked by the anti-health pass protests in August.

On the far right, can a Trump-inspired candidate thwart Le Pen's strategy?

As in 2017, when she obtained 34% of the vote in the second round against Macron, Marine Le Pen is still the main far-right candidate. In practice, she is trying to learn the lessons of the 2017 failure and is now working on her “presidentiability”. After renaming the party "Rassemblement National" (RN), her programme is also evolving to become more mainstream: abandoning 'Frexit' (France leaving the European Union), maintaining the euro and introducing proposals on the environment.

She is now trying to appear more reasonable on public finance issues though she remains firmly eurosceptic and hostile to immigration, and she maintains her opposition to any reform of pensions unless it's to reduce the minimum legal retirement age. Le Pen's programme would include two proposals to nationalise the motorways and privatise public broadcasting.

The RN's setback in the regional and departmental elections of 2021 nevertheless casts doubt on her ability to win. According to the latest polls, she could gather between 19 and 23% of voting intentions in the first round, which would qualify her again for a second round with Macron. She will be challenged on the far right by Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, who will once again campaign on a pro-sovereignty line, with proposals to relocate jobs, lower wage costs and abolish "right of the soil" nationality laws to restrict immigration. But polls currently show that his chances are no better than in 2017.

French presidential elections always hold the potential for a surprise

French presidential elections always hold the potential for a surprise. This year, it could come from the candidacy of polemicist Eric Zemmour, who threatens to upend support for Le Pen and the candidate of the right. Although he has not yet declared his candidacy, political speculation is mounting.

A potential candidacy not unlike that of Donald Trump, Zemmour has made a name for himself in France by defending his hard-line views on immigration, Islam’s place in France and national identity and endorsing the theory of the "great replacement", a far-right conspiracy theory that warns of a deliberate substitution of the French and European white population by a fast-growing non-European population. Despite regularly crossing red lines, his audience has continuously grown on CNews, a Fox News-like French TV channel, and his books have become bestsellers. So much so that he has managed to blur the lines between media and politics: the latest polls now show that 10% of voters support Zemmour, up from 7% a week earlier and 5% in July - outscoring some of France’s established parties, including the Socialist mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo.

Zemmour's candidacy would still lack credibility and he suffers from a divisive personality, but his straight talk increasingly appeals to a generation that has been disappointed by politicians and that mistrusts the media. Zemmour has already achieved his first success: imposing his political agenda as unavoidable for 2022.

France presidential election second round (%)

Right-wing candidates in search of unity

How Les Républicains (LR) choose to nominate their candidate for the presidential elections remains a question for now, but the party has launched a large qualitative survey to support the decision. Xavier Bertrand is still leading the field of candidates, especially when it comes to convincing the more conservative party members, but he does not have enough support to win the nomination without a fight. Among the other candidates for the nomination, Valérie Pécresse is the main challenger and could benefit from open primaries.

Pécresse and Bertrand both share a liberal economic agenda, focusing on business competitiveness, corporate tax cuts and proposals to reform migration policy. They also share a similar political trajectory, breaking away from the LR party and recently reappointed as president of their region. But their rhetoric differs. Bertrand has already portrayed himself as the antithesis of Macron, especially when it comes to keeping Le Pen out of power, whilst Pécresse is claiming Margaret Thatcher's legacy. In either scenario, a second-round between one of them and Macron still seems a distant prospect.

On the left, an wide array of candidates

Jean-Luc Mélenchon (La France Insoumise), the far-left candidate who obtained 19.58% in the 2017 election, already announced some time ago that he will be a candidate for the third time but he has yet to kick-start his campaign. He will certainly benefit from a well-constructed programme, inherited from the previous campaign in 2017. He shares broad ambitions for a green investment plan with the Socialists and the Greens. But, among other points, his stance on the cancellation of the controversial El Khomri law on labour (which allows more flexibility in terms of working hours, individual negotiation and dismissals) and his stance on European diplomacy differ with them. So far, he has only agreed on a "non-aggression" pact with the other left candidates.

A future green candidate will need more than traditional campaigning rhetoric

In the past month, Yannick Jadot appeared as the clear leader of the Greens, pushing for a common strategy of the left towards 2022. But despite his efforts, he will not avoid the Greens' primary. He will face Sandrine Rousseau in the second round from 25 to 28 September and it is not at all certain that he will win. So far, the primary campaign of the environmentalists has been unusually calm in France, highlighting key policy proposals to decarbonise France; investments in the energy transition, the phasing out of fossil fuels, a higher carbon price and even degrowth. But the future green candidate will need more than that if he or she hopes to thwart the announced triangle between Macron, Le Pen and the candidate of Les Républicains.

Despite the Socialists' disastrous results in 2017, the party has proved that it still counts in the political landscape after its electoral successes in both municipal and regional elections. Anne Hidalgo, mayor of Paris, recently declared herself a presidential candidate (she still needs to obtain the official nomination of the Socialist party, which shouldn't be an obstacle). Her economic programme will be based on proposals in favour of green transition (she regularly refers to the Biden administration's recovery plans as a model) and a reduction of social inequalities by increasing the salaries of the middle and working classes. She has proposed, for example, to at least double teachers' salaries. Her electorate is relatively close to that of Emmanuel Macron, but her ideological proximity is with the greens, which could suggest an alliance for the presidential elections.

The real challenge for the left lies in the wide array of candidates that will likely split the vote

In fact, Hidalgo and Jadot have already agreed in principle to send a joint candidate to the presidential election. But both hope to carry the banner of this alliance, so nothing has been settled yet. The latest polls show that they are both faring quite poorly in the polls (around 7% individually) so neither of them is emerging as a clear leader. And in the meantime, others are trying their luck, adding to the wide array of candidates who hope to take on the left agenda for 2022. This will probably split the vote.

In 2017, voters showed an appetite for a newcomer, Emmanuel Macron, and a proposal for radical change. But his revolution did not happen because his mandate was devoted to crisis management (Yellow Vests, Covid....). So the left could, in theory, try to harness those disappointed voters around the green transition and a social project. But without Jean-Luc Mélenchon (La France insoumise), who is planning to go it alone for the third time, the left appears to be a toothless tiger.

Declaring one's candidacy is, at the moment, a purely political act that does not guarantee a place on the starting line. As the campaign progresses, some may throw in the towel or join another candidate. The final line-up will only be known in March 2022 with the official submission of the 500 sponsorships of elected representatives required for any presidential candidacy, their validation by the Constitutional Council and the publication by the latter of the official list of candidates.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article