Money growth at last in the Eurozone, but don’t expect inflation running hot

The recent surge in broad money supply has been remarkable, but this is mainly due to surging liquidity needs during the lockdown. But chances of higher inflation are muted as investment opportunities are likely to remain far and few between when liquidity needs subside. And then there is the weakening relationship between money and inflation too

A positive of coronavirus crisis- money growth hits record highs

What the ECB hasn't been able to do for years with extraordinary monetary policy has happened in just a few months of coronavirus crisis - accelerating money growth.

Years of asset purchases have had a relatively small impact on the amount of money in circulation in the economy. Yes, quantitative easing has caused money growth to increase, but most visibly in the form of higher commercial bank reserves at the ECB - base money.

Broad money supply - M3, was relatively little affected as credit demand remained weak or, as phrased by some critics, QE remained stuck in the financial system and failed to reach the real economy. The coronavirus crisis has changed the picture completely.

What the ECB hasn't been able to do for years has happened in just a few months of the coronavirus crisis - accelerating money growth

Since the formation of the eurozone, there has not been such a monthly increase in broad money as we saw in March, with April and May, also ranking among the months with the fastest growth in broad money ever recorded. Does this mean that inflation is on the cards?

Let's break down what's happened over recent months

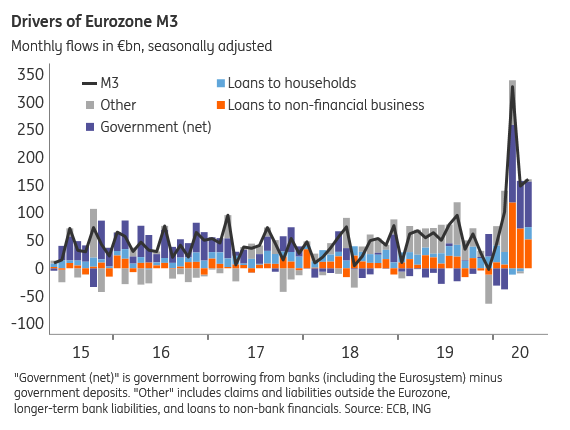

The sudden surge in broad money is a consequence of the coronavirus crisis as lockdowns left businesses struggling for liquidity with little revenues coming in and costs continuing to run high. Governments have provided liquidity relief chiefly in the form of tax deferrals and income support for businesses and consumers. Roughly half of the observed increase in household and business deposits at eurozone banks is related to such support measures. The other half comes from increased bank lending – in turn, helped by quickly devised and generous government guarantee schemes.

Deposits by households and businesses increased by €529bn from March to May, while loans to these sectors grew by €256bn - a record by the way!

Deposits by households and businesses increased by €529bn from March to May, while loans to these sectors grew by €256bn. That too is a record, by the way. This is therefore not the usual surge in broad money that may lead to higher growth and inflation. Quite the opposite, it seems to be an increase that is mainly related to liquidity hoarding, precautionary saving, postponed and cancelled spending.

The root cause is the lockdown and uncertainty. Indeed, the most recent ECB bank lending survey indicated that demand for loans for investment purposes has been declining, which makes sense given the depth of the economic decline and the prevalent uncertainty.

Will all this money not have a meaningful impact on the economy?

The surge in deposits is likely to fade now that lockdowns are gradually being eased.

As the economy restarts, business emergency liquidity needs are likely to decrease. Bank lending demand will fall and governments can shift their focus away from liquidity support. Over time, deferred taxes will be paid and loans will be paid down. This will reduce deposits in the system and thus M3. So, the increase in broad money seems to be of a temporary nature. However, it is unlikely that businesses, SMEs in particular, will be able to repay the additional loans instantly, as lost turnover will only be recouped slowly, and for some sectors never. This means that the liquidity provided by governments and banks during the lockdown will be in the system for quite some time – and partly forever, insofar loans and taxes will never be repaid and need to be written off.

The recent surge does mean that substantial amounts of money have entered the system, and could remain there for some years which means that there is potential for some upward pressure on inflation. The big question regarding potential upward pressure on inflation is what companies are going to do with the extra money in the bank once the immediate liquidity need has faded.

First of all, the increased non-financial business savings that are due to deferred taxes can be expected to fade over the coming quarters as the deferred payments become due. If governments use these funds to reduce their budget deficit, the money will disappear from the system.

Secondly, if there is little opportunity for investment of money originally borrowed out of precautionary motives, it is a likely scenario that businesses pay back these loans as we do not expect GDP to return to pre-crisis levels before 2023. That leaves a large amount of excess capacity for a while to come, which generally translates to a sluggish investment environment. Despite very favourable borrowing conditions, this would be the most logical option. That would, in turn, destroy the money from the system and put downward pressure on money growth.

Only a part of the increase in money supply will remain in the system more permanently – the part reflecting taxes and loans that will never be paid back as businesses go bust and the part that businesses decide to invest and not pay back. This has the potential to provide some upward pressure on inflation as conventional economic thought would suggest.

For now, M3 is about 3.5% higher than it would have been if it had grown at the pre-Covid-19 trend, but in our view, it is too little to make a difference

In our view, it is too little to make a difference. For now, M3 is about 3.5% higher than it would have been if it had grown at the pre-Covid-19 trend. But also because the relationship between money growth and inflation has unravelled significantly in the past decade, with simple correlations between money growth and inflation diminishing. This is explained in part by asset purchases, but the relationship with bank lending has also declined.

This suggests other factors have become more important in determining inflation than the availability of money in the system. Add deflationary forces to the mix, it is unlikely that the jump in broad money will be very noticeable in inflation in the coming quarters.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more