Eurozone: Diminishing expectations

While the eurozone’s third-quarter growth was negatively affected by special factors, the rebound in the fourth quarter has so far been rather muted. So although the European Central Bank is still proceeding with its exit policy, the chances of a 2019 rate increase are diminishing

More political uncertainty

Things have been moving on the political front in Europe. A deal on Brexit has been reached, though its approval in the UK parliament is not yet guaranteed, meaning that uncertainty could still linger in the run-up to 29 March 2019 and the turbulence of a hard Brexit can still not be dismissed entirely.

In the eurozone, French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel have taken the surprising step to follow-up on previous agreements and establish a eurozone budget. This could be a major step forward to solidify the structure of the eurozone. However, when looking at the details, the intention seems more important than the substance, because what is on the table now so far lacks the muscle to smooth asymmetric shocks within the bloc. On top of that, a number of member states, the so-called New Hanseatic League, under informal leadership of the Netherlands, are eager to block any European initiative that has the faintest whiff of debt mutualisation in it.

So in the short run, the promised further deepening of eurozone integration will remain limited to making the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) a financial backstop for bank resolutions and probably a very tiny, though symbolic, eurozone budget. The latter will be larded with good intentions but with little commitment to finalising a banking union, morphing the ESM into a European Monetary Fund, eurozone revenues or pooling of debt. As a consequence, the solidity of the Monetary Union could be tested again, once economic growth falters.

In the meantime, there is a new episode in the Italian story. After looking at the Italian budget plans the European Commission concluded that “the debt criterion …should be considered as not complied with, and that a debt-based Excessive Deficit Procedure is thus warranted”. This will have to be approved by the Council, probably in January. After this time, Italy will have between three and six months to put corrective measures in place. This means that a judgment on Italy’s efforts may not be made until after the European elections, and even then, a final judgement is not strictly necessary.

Fortunately, the Italian government has realised that higher bond yields are now also seeping through into bank lending rates. In talks with the European Commission, the Italian government has suggested that there is no urgency to implement all of its plans immediately. The conciliatory tone might push bond yields down somewhat although this doesn’t alter the fact that most of the government’s measures will do little to improve Italy’s growth potential. Another piece of comfort for the markets is the fact that in the latest Eurobarometer (survey taken in October), support for the euro in Italy actually increased by a whopping 12 percentage points to stand at 57% (against 30% detractors).

Having the euro is a good thing for my country

Slowdown continues

Meanwhile, the economic slowdown in the eurozone continues. The composite PMI dropped to an almost four-year low in November, from 53.1 to 52.4. Forward-looking indicators like new orders don’t herald a strong rebound. Weakening export orders, across both industry and services, are a testament to the fact that the eurozone is quite sensitive to the growth slowdown in the emerging world. Europe’s biggest economy Germany was hit by the new emissions standards in the third quarter, creating severe production problems in the automotive industry, and the country is not necessarily going to see a V-shaped rebound in the fourth quarter. The Ifo index actually dropped for the third consecutive month in November, with both the current assessment and the expectations components losing momentum.

The good news is that the recent significant drop in energy prices will be a boon for both consumers and businesses. So the fourth quarter could see growth pick up a bit after a very weak third quarter, but we wouldn’t get overexcited. While ECB President Mario Draghi is still putting on a brave face, the minutes of the October meeting of the Governing Council revealed that some members had their doubts about the growth outlook. We believe that the staff projections, now pencilling in 1.8% and 1.7% GDP growth for 2019 and 2020, respectively, will inevitably be revised down at the next forecast round in December. Our own forecast now stands at 1.4% and 1.3% for 2019 and 2020, respectively, while we slightly lowered our 2018 forecast to 1.9% on the back of a weaker-than-expected growth rebound in the fourth quarter.

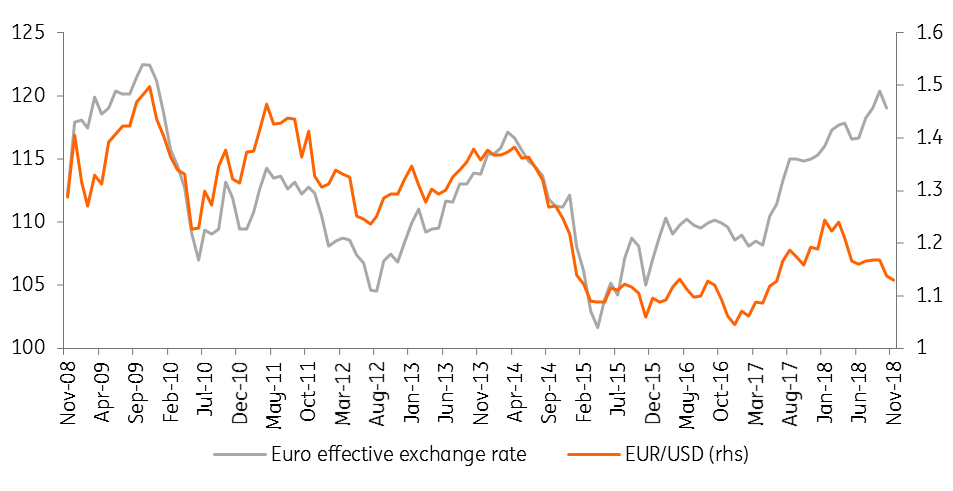

Euro exchange rate: stronger than you think

Outlook for inflation and policy

The slower growth picture begs the question to what extent inflation will pick up. Lower oil prices will have some downward impact on headline inflation in the months ahead. Due to the tightness in the labour market, wages are starting to rise, which could ultimately drive core inflation higher. However, the ECB notes that up until now, businesses have absorbed most of the increase in input costs with narrower profit margins. It remains to be seen whether they will be able to restore margins, as pricing power could be hurt by both slower growth and competition from the emerging world, which may benefit from depreciated currencies. We have revised our headline inflation forecast downwards to 1.6% for 2019 and 1.7% for 2020 and still think that the ECB’s expected pick-up in core inflation to 1.8% in 2020 is too optimistic.

All of this means that the ‘normalisation’ of the ECB’s monetary policy is going to be a long and winding road. For the time being, we still think that the ECB will bring the deposit rate to 0% by the end of the first quarter of 2020. But that’s all we expect for now and if some of the adverse risks materialise, we might end up with no rate change at all over the next two years. If the Italian economy remains lacklustre (we’re forecasting only 0.9% growth in 2019) and Italian bond yields remain high, we believe the ECB will launch a new round of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO) to avoid a tightening of monetary conditions in the peninsula.

Download

Download article30 November 2018

December Economic Update: Avoiding Hard Choices This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more