Energy Performance of Buildings Directive: A step closer to the finish line

The Energy Performance of Building Directive recast is moving a step closer to the finish line by reaching a provisional agreement. Renovation goals for residential and non-residential buildings and the gradual phasing out of fossil fuel heating are part of the changes. Banks are expected to have an essential role in financing the transition

Introduction

The European Union established a strategic agenda to tackle climate change and transform the EU economy into a climate-neutral, green and fair society. The European Climate Law enforced in 2021 marked a major commitment to the transition by making the EU’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction by at least 55% by 2030 a legal requirement.

To reach this target, a set of proposals to revise and update the EU legislation was introduced through the “Fit for 55” package. The legislation proposed amendments in 12 different policy areas ranging from land use and forestry to aviation and maritime transport. One of the most contingent points is the review of the Energy Performance of Building Directive (EPBD), as it contains economic, social and financial characteristics.

This piece provides an update on the legislative development of the EPBD following the publication of the provisional agreement by the European Commission.

Fit for 55 quick peak

The Fit for 55 package serves as a framework to attain EU climate objectives such as ensuring a just transition, maintaining the Union's competitiveness and positioning the EU as a leader in the fight against climate change. It proposes legislation in the following 12 policy areas:

- EU emission trading system (ETS)

- Effort sharing regulation

- Land use and forestry (LULUCF)

- Alternative fuels infrastructure

- Carbon border adjustment mechanism

- Social climate fund

- RefuelEU aviation and FuelEU maritime

- CO2 emission standards for cars and vans

- Energy taxation

- Renewable energy

- Energy efficiency

- Energy performance of buildings (EPBD)

Why the EPBD is a central piece of the EU climate transition

European buildings account for 40% of the energy consumed and 36% of energy-related direct and indirect GHG emissions. Tackling these emissions is thus crucial to reach the Union’s emission reduction goal.

Furthermore, the EU plan doesn’t only aim to reduce emissions but also intends to ensure that the transition toward a greener society is a just one. Social aspects and implications of the changes are, therefore, an important part of the discussions. This is fundamental to remember when discussing the EPBD recast for several reasons.

Firstly, improving the energy efficiency of buildings can be extremely costly. However, this cost varies depending on the country, building type (apartment vs individual home) and current energy efficiency. The EU also notes major differences between countries’ building stock efficiency.

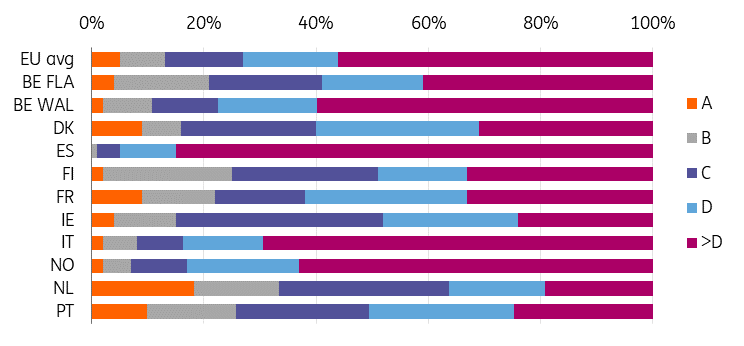

Significant differences in EPC distribution between countries

The EU estimates that 75% of the Union building stock is energy inefficient

VEKA estimates that renovation costs of inefficient buildings vary between €15,000 and €100,000. Nonetheless, important national variations exist. In Germany and the Netherlands, the average renovation costs lie between €15,000 and €30,000, and Belgian homeowners face higher costs with, on average, €50,000.

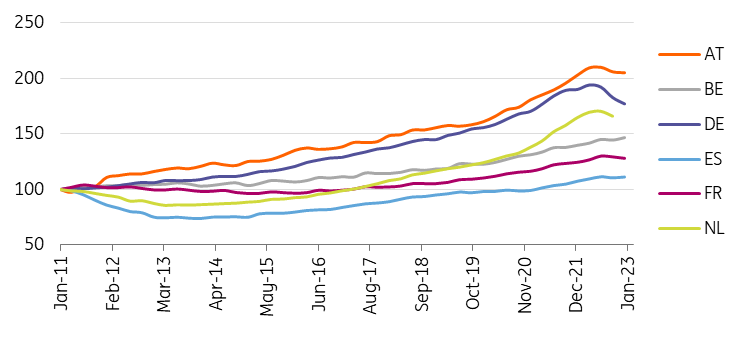

Also, research from our economists shows that renovation costs have increased faster than inflation. Despite that, renovations represent a significant share of the building industry in the Union. The study also highlights that Western European countries have a higher share of renovation out of their total building production.

Renovations represent a significant share of building industry despite costs increasing faster than inflation

The second variable to consider is the ownership profile. Just as for the renovation costs, ownership varies across the EU. However, it’s a crucial point in the discussion as it determines the feasibility of energy renovation.

Indeed, significant differences persist between EU jurisdictions. For instance, Belgium shows not only a high rate of ownership but also a high rate of low-income ownership, with 44% of the lower-income population owning property. This share is only 20% and 15% for Germany and the Netherlands, respectively. Countries with an important share of low-income homeowners can expect more difficulties in improving the national renovation rates as access to liquidity is more complex for this part of the population.

Home ownership rate varies across countries as well as homeowners' profile

Financial institutions are directly affected by the renovation wave as most households will need a loan to make the necessary changes. Furthermore, the sector faces increased devaluation risks through the existence of energy premia. We'll be looking at that shortly.

All in all, the Energy Performance of Building Directive combines financial, social and technical aspects, making it a significant challenge for the EU to reach its GHG emission reduction goals.

A step closer to the finish line

The European Commission's legislative proposal to revise the EPBD was adopted in December 2021. Since then, the Council of the EU and European Parliament also drafted their own proposals. Each institution proposed a slightly different approach to reach the European objective and enact the transition.

In our previous pieces “Energy Performance of Building Directive review: Major renovations ahead” and “Energy Performance of Building Directive review: how will banks be affected?” we looked into both the Commission’s and the Council’s proposals and their expected impacts on the banking sector.

After months of Trilogue negotiations, a provisional agreement was reached on 7 December, 2023. The Trilogue sessions aimed to develop a common text reviewing the current EPBD. The last step of the legislative process will be for the European Parliament and Council to vote on the provisional agreement to formally endorse it. If the vote is successful, the policy should be enforced in 2025.

Four main changes to the current EPBD

This section dives into the main changes the recast makes to the EPBD and how that diverges from the previous policy versions.

Renovation goals

Starting with residential buildings, the provisional agreement states that each Member State (MS) will adopt their own national trajectory to reduce its building stock’s average primary energy use. This should be in line with the 2030, 2040, and 2050 targets contained in the MS building renovation plan and should identify the number of buildings, building units, and floor areas to be renovated annually.

This is a significant change from the previously proposed policies as these were including renovation targets based on minimum energy performance criteria. Instead, the agreement focuses on diminishing energy consumption across all houses rather than only the worst-performing buildings.

The agreement states that the reduction in average primary energy use should be 16% by 2030 and 20-22% by 2035 relative to 2020 levels. MS must reach these reduction targets but are free to choose which buildings to target as well as which political measures to enforce (i.e., minimum energy performance standards, technical assistance, and financial support measures).

However, to ensure that the Union’s worst-performing buildings are gradually refurbished, the EPBD review specifies that at least 55% of the decrease in average primary energy use should stem from the renovation of the worst-performing buildings nationally.

Worst-performing buildings are defined as buildings which are within the 43% of buildings with the lowest energy performance in the national building stock.

Moving to non-residential buildings, the agreement keeps the reduction target as proposed before the negotiations. Non-residential buildings will, therefore, need to follow Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) set by Member States.

This gradual improvement should lead to the renovation of at least 16% of the worst-performing buildings by 2030 and 26% of those by 2033. Member States will be able to express this threshold in either primary or final energy use.

In the case of a seriously damaging natural disaster, a Member State may temporarily adjust the maximum energy performance threshold so that the renovation of the damaged non-residential buildings replaces the renovation of other worse-performing buildings. This should, however, be done whilst ensuring that the percentage of stock undergoing renovation remains stable.

Additionally, all new residential and non-residential buildings will have to have zero on-site emission of fossil fuels as of January 2030 and January 2028 for publicly owned buildings.

MS will, nonetheless, be able to exempt certain categories of buildings from the previously explained requirements. For non-residential buildings, they should communicate the criteria for such exemption in the National building renovation plan and compensate the exempted stock with renovation in equivalent improvement elsewhere in their non-residential building stock.

Energy Performance Criteria

One of the most contingent points in the EPBD is harmonising the Energy Performance Criteria (EPC). Indeed, the current labelling system significantly varies across countries. These differences make it very difficult for the Union to set harmonised minimum energy performance goals. It also hinders the building stock comparison between Member States.

The current EPC labelling significantly hinders comparison between countries

This is even the case between regions as in Belgium with three different scales

The provisional agreement states that EPCs shall be based on the common EU template with common criteria. The scale shall be between letters A and G, with A corresponding to zero-emission buildings and G to the worst-performing building of the national building stock at the time of enforcement. Classes B to F must have an appropriate distribution of energy performance indicators among each class.

Zero-emission buildings are defined as buildings with a very high energy performance, requiring zero or a very low amount of energy, producing zero on-site carbon emissions from fossil fuels and producing zero or a very low amount of operational greenhouse gas emissions.

Nearly zero-energy buildings are defined as buildings with a very high energy performance which cannot be lower than the 2023 cost-optimal level reported by MS and where the nearly zero or very low amount of energy required is covered to a very significant extent by energy from renewable sources, including energy from renewable sources produces on-site or nearby.

MS that already implemented A0 as a zero-emission building may keep this designation instead of A. Furthermore, MS that have rescaled their EPC classes on or after January 2019 and before the enforcement of the EPBD IV may postpone the rescaling of their EPC until December 2029.

The review also specifies that financing measures should be enforced to incentivise the renovation. Those should specifically target vulnerable homeowners and worst-performing buildings in order to mitigate energy poverty. It also underlines safeguards for tenants, reducing eviction risks and disproportionate rent increases at MS level.

National Building Renovation Plans

To ensure that MS reach the emission reduction targets, national Building Renovation Plans will be enforced. These must, on the one hand, have a stronger focus on financing the renovation and, on the other hand, ensure the availability of skilled workers to proceed with the sustainable renovations. Thus, member states are expected to share an outline of financial measures, investment needs and administrative resources to reach their national renovation milestones.

Alongside their Building Renovation Plans, MS will have to set up building renovation passport schemes. These documents will provide tailored roadmaps for the renovation of specific buildings in several steps to significantly improve energy performance. It would give the opportunity to clearly map, through expert certifications, what can be done to improve the energy performance of a specific building.

The creation of one-stop shops (OSS) is one of the mandatory indicators included in the template of the national Building Renovation Plans. These suppliers provide “integrated solutions” as services and assistance in multiple steps of an energy renovation, helping with the facilitation and/or coordination of renovation work. For buildings with an EPC label below C, MS will be required to invite owners to an OSS to receive renovation advice either immediately after the EPC expires or five years after the issuance of the performance certificate.

A report from the European Commission (2021) finds that these OSS solutions could incentivise between 5% and 6% of the renovation volume desired by the renovation wave in 2030.

Energy topics

The EPBD recast will also include articles to gradually phase out fossil fuel boilers. Indeed, as of January 2025, subsidies for stand-alone fossil fuel boilers will be banned. Alongside will also come a legal basis for MS to implement regulation on heat generators. The EU wants to completely phase out boilers powered by fossil fuels by 2040.

The agreement also states that MS must ensure that new buildings are solar-ready. In other words, that they are fit to host rooftop photovoltaic or solar thermal installations. This should be the case where it is technically, economically and functionally feasible for new public and non-residential buildings over 250m2 as of December 2026. All existing public buildings (over 2000m2) as of the end of 2027, all of those over 750m2 as of December 2028 and finally, all public buildings over 250m2 as of December 2030.

Banks on the first line of action

Changes stemming from the EPBD review will affect both society and financial institutions as these will have to play a major role in financing renovation.

The EPBD recast states that financial institutions should be mobilised to incentivise building renovation. Furthermore, MS should encourage banks to promote targeted financial products, grants, and subsidies to improve the energy performance of vulnerable households and owners of the worst-performing building stock. Finally, the Commission is expected to publish a voluntary framework to help financial institutions target and increase lending volumes in energy renovations.

The housing market differs a lot between Member States. Hence, the impact of the EPBD recast will also vary depending on the country. It’s important to consider national specificities when addressing the potential effect of the Directive. Before looking into potential effects on banks, six important variables must be considered to estimate the impact of the Directive, these six variables are discussed in more detailed in our previous piece that you can find here.

Firstly, the availability of sufficient and qualitative data on buildings’ energy efficiency varies significantly between jurisdictions. Consequently, investments to generate and update these data points will also fluctuate.

Secondly, the current quality of the building stock is also greatly varying, as mentioned previously. This adds to structural differences in building types.

Thirdly, some countries already see the presence of an energy premium on their housing and real estate market. For example, in Belgium, ERA, the country’s largest real estate agent, showed that Flemish homes with an EPC score of A or B became 1.5% more expensive in 2023. In contrast, homes with a lower score (E or F) see a price decline of 1.6% over the same period. Our economists expect these energy efficiency premiums to widen in the coming years. Read more on this here. The generalisation and growing importance of EPCs will, therefore, have an impact on the overall market price.

House prices have slightly decreased since 2022 due to the high interest rate environment

Index Jan 2011 = 100

Also, as shown in the previous section, renovation costs vary greatly between MS, which ultimately impacts renovation feasibility. This is accentuated by the national ownership profile. Indeed, a higher share of low-income homeowners will also hinder energy renovation, especially in countries with higher refurbishing costs.

This brings us to the last point: liquidity access. The feasibility of the EU renovation wave will depend on homeowner’s access to sufficient liquidity to fund the necessary refurbishing. Ultimately, this last variable pushes banks to the first line to enact this transition. Nonetheless, this is not without consequences for the financial sector.

Overall, the changes presented in the transitional agreement could negatively affect the banking sector through two channels. The first one is the enforcement of the Minimum Energy Performance of buildings. Setting a minimum required energy performance or EPC could reduce the value of the least efficient part of the bank’s portfolio. Indeed, as presented before, some countries like Belgium have already highlighted an energy premium on high EPC houses and discounts on the worst-performing stock.

However, as the provisional agreement applies MEPS only to non-residential buildings and focuses on an average efficiency approach for residential ones, we expect this effect to be less important than projected previously.

The provisional agreement did, however, keep the option for MS to exclude certain types of buildings from energy efficiency requirements. While this makes sense to protect the integrity of historical buildings, it may provoke a large devaluation of some buildings with the presence of energy efficiency premiums on the market. Hence, depending on a bank's portfolio composition, it could imply higher stranded asset risk for institutions with a large share of EPBD-excluded buildings on their book.

The EPBD recast is also expected to impact banks as they will have to create and develop an EPC database for their portfolio. The cost of retrieving sufficient and qualitative data on building efficiency remains one of the main challenges for the sector. Without qualitative information on the state of credit institution’s building stock, it also hinders the enforcement of adequate measures and financial incentives for renovation.

On the bright side, this Directive recast will open and help develop a new market for renovation loans by setting a clearer direction for the sustainable transition. As the regulation outline becomes clearer, financial institutions can estimate and prepare for the upcoming renovation wave.

With the renovation wave also comes the opportunity for financial institutions to develop products allowing all homeowners to access the necessary financial means and take a concrete role in making this transition a just one.

Even if the Directive review doesn’t state direct penalties for infringements, not respecting or playing an active role in the enforcement of the new requirements can have a serious reputational effect as well as increasing litigation risks for banks.

The provisional agreement reached at the end of 2023 brings the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive a step closer to the finish line. The most important change concerns residential buildings' renovation goals. Indeed, as the proposals all included a minimum energy performance approach, the agreed text changes this to rather look at improving national averages while keeping the MEPs for non-residential buildings.

The clause ensuring that 55% of the energy reduction stems from the worst energy-performing buildings is the main addition to the existing proposals. The EPC scale harmonisation will ensure more comparability between countries building stock, however this harmonisation will be delayed to the end of 2029 for some countries. The agreement underscores stricter regulation on fossil fuels, including their gradual phasing out, but also more lenient rules on the establishment of solar energy for buildings.

All in all, changes stemming from the EPBD recast will affect both society and financial institutions, as these will have to play a major role in financing renovations.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article