Fashion and new business models

Fashion by its very definition needs to reflect the present and offer a glimpse into the future. Yet when it comes to being a sustainable industry, more needs to be done for it to catch up.

The earth is straining under pressure from people and their products, making environmental management one of the biggest issues we face. People have been urged to consider how they use transport, heat and cool homes and use plastic. Another less apparent, but highly relevant issue, is the way we dress. The ease with which we can buy clothes and footwear cheaply online has driven strong growth in the fashion industry.

Writing in Forbes in 2019, Gulnaz Khusainova noted: “Fashion has a sustainability problem. In 2015 the industry was responsible for the emission of 1,715 million tons of CO2. It’s about 5.4% of the 32.1 billion tons of global carbon emissions and just second after the oil and gas industry. Global apparel and footwear consumption are expected to nearly double in the next 15 years–and so its negative impact on the environment.”

Four separate ING reports on the developing circular economy shed some light on why the fashion industry continues to operate this way.

The three Rs

The circular economy is based on the principle of the “Three Rs” – reduce, reuse and recycle. This approach ideally works across many different products ranging from clothes, furniture, white goods and cars. But there is a case to argue that clothes don’t easily fit into this way of thinking. Evidence suggests attire and footwear are often seen as disposable rather than recyclable.

Don’t darn it

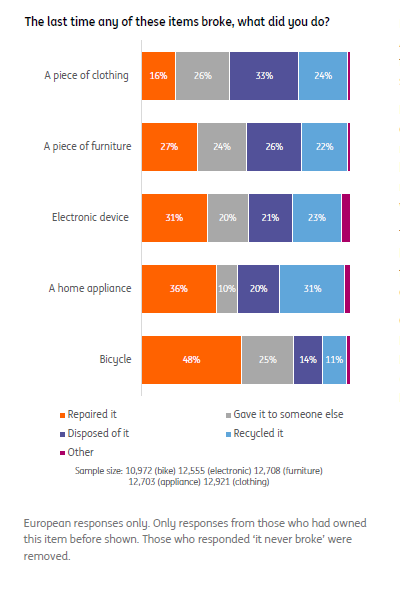

When asked what happened to a variety of items when they broke, clothing was least likely to be either repaired or given to someone else compared to furniture, an electronic device, a home appliance or a bicycle. This was one of the findings of the ING International survey title “Circular economy: Consumers seek help”. The November 2019 survey asked nearly 15,000 people in 15 countries across Europe, the USA and Australia about their attitudes to reusing and recycling.

Environmental attitudes

Similar results were found in a separate 2020 survey by ING’s wholesale bank on consumer attitudes to the circular economy. The survey asked around 15,000 people globally how important various considerations were when buying either clothing, food or electronic items. Environmental impact (at 33%) and the brand’s environmental reputation (at 31%) lagged behind price (56%), quality (54%) and convenience (41%). Results recorded for food and electronic items were similar. Environmental issues are not top of mind when it comes to buying clothing.

Making clothing stand out

Several reasons could be behind a lack of understanding the environmental impact clothing has and society’s growing acceptance of fast fashion.

One aspect is salience. Many cannot make the connection between what they wear and waste. Asked what they saw as the most pressing problem for the environment from a list of plastic waste, climate change, air pollution, depletion of natural resources and loss of biodiversity, plastic waste was considered broadly as important as climate change, according the nearly 13,000 people across Europe in the ING International Survey. I recognise that clothing is not in the list respondents could choose from, but the high ranking of plastic waste is easy to understand. Plastic waste is rightly front of people’s minds. It is easy to see as we experience it every day and the Blue Planet effect plays an important role. Behavioural scientists call this salience bias.

Make no mistake. Plastic waste is a problem. But there can be further problems if people believe recycling their plastic waste alone means they are doing their bit for the environment. Again, behavioural scientists have a phrase for this. It’s called moral licencing. It’s a failure to link all your actions to the result you are trying to achieve.

Change is not easy. You cannot dress it up

It’s easy to call for people to change their behaviour and do their share for the environment. But it is not easy. Several factors make changing behaviour difficult. In discussing the headwinds to the circular economy, Mark Cliffe, the head of ING’s New Horizon Hub, notes that financing circular economy business models is complex. Business models need to be redesigned. This includes the clothing industry. Consider one important challenge. Repairing and altering clothes often requires skilled labour. But the costs of labour have increased over time while the price of materials has tended to fall. It can be cheaper to buy new rather than repair.

When you think more deeply about the challenges faced by making circular business models work, it is little wonder that Mirjam Bani and Marieke Blom from ING Netherlands argue that the world economy is becoming less circular. They argue that without policy intervention, the circular economy will shrink further.

Shrinkage is not what you want when it comes to clothing. The same can be said for the circular economy. Just as we care for the clothes we wear, we should do so for the planet on which we depend. We need to approach business and finance differently to make this possible.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article