Bank Outlook 2023: Banks will keep exploring new ways of sustainable funding

Against a backdrop of slower lending growth, it will be hard for banks to continue the sustainable funding pace of the past two years. Next year may prove to be too early to fully capitalise on the broad range of new opportunities to sustainably finance bank loan portfolios, as the supporting regulatory landscape is only gradually gaining shape

The integration of environmental and social sustainability aspects into the business operations of banks has strongly accelerated in recent years. This has not only been driven by regulation but also by the wider societal sense of urgency to combat climate change and protect the environment.

ESG is a top priority for banks, including in their capital markets presence

Banks have become more vocal and transparent about their environmental and social strategies and targets. These not only comprise actions taken to reduce their own climate footprint, but also involve actively engaging with clients to support them in improving their environmental footprint, or distancing themselves from sectors deemed highly polluting, such as fossil fuels. They develop dedicated lending products at attractive terms, such as green mortgage loans, for the financing of environmentally sustainable projects or assets.

At the same time, banks give depositors and investors the opportunity to put their cash to work in a sustainable way through green deposits or by issuing green/social bonds. When it comes to their own capital markets presence, some issuers even try to set an example by assigning lead managing roles to diversity and inclusion firms. As we look forward to 2023, this article focuses on the sustainable funding of banks through green and social bonds.

Sustainable bank bond supply to lose some steam

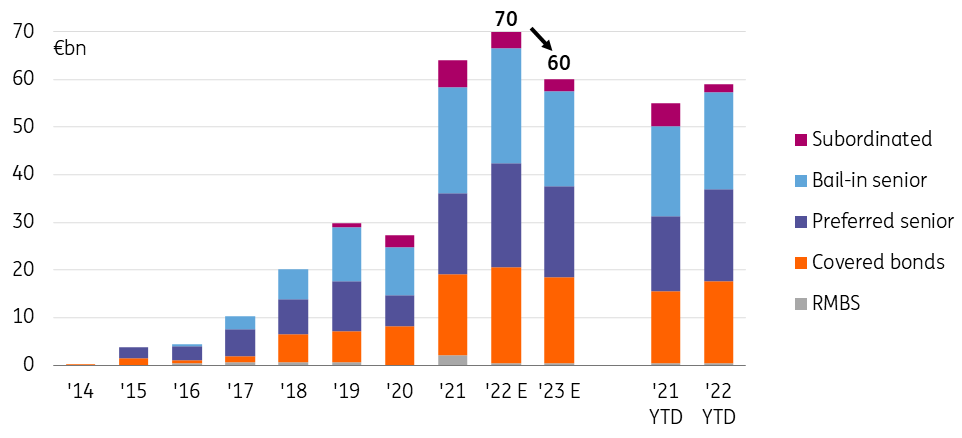

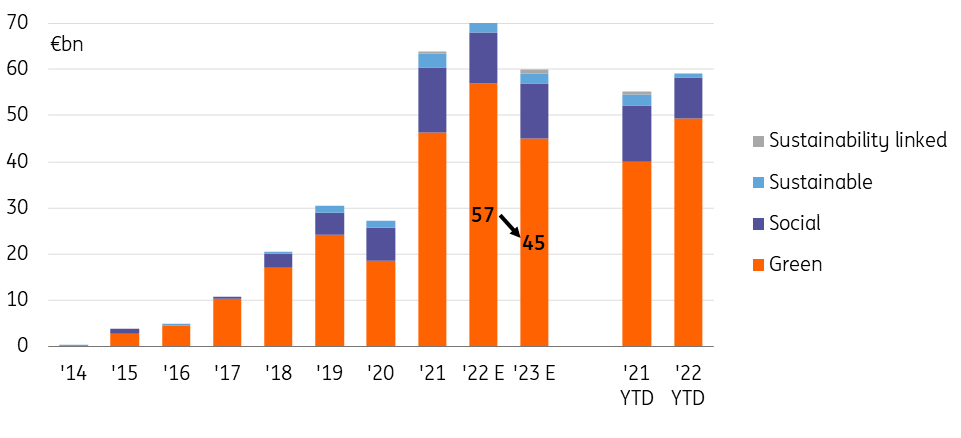

Green and/or social bonds have become increasingly popular as a source of funding for banks in recent years. In 2021, banks issued a record €64bn in euro sustainable bonds through different types of instruments, ranging from covered bonds to subordinated bonds. This was more than double the supply seen in previous years. Banks are well on their way to breaking this record in 2022.

Sustainable bank bond supply will lose some pace in 2023

During the first ten months of this year, banks issued €58bn in sustainable bonds, of which €17bn were in covered bonds, €19bn in preferred senior, €20bn in bail-in senior and €2bn in subordinated paper. This is up from €54bn over the same period last year. While green issuance is more than €10bn higher than last year, social and sustainability supply falls €7bn short of the first ten months of 2021. This largely reflects the lower refinancing of Covid-19 related small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) and/or healthcare loans through social bonds.

Green supply, in particular, will likely be softer in 2023

For 2023, we expect less issuance in sustainable bank bonds (€60bn) despite the high refinancing need of banks due to the targeted longer-term refinancing operation (TLTRO)-III expirations. The major reason is the anticipated slower lending growth. This will mitigate the ability of banks to naturally expand their green and social loan books. Meanwhile, the growth potential for supply via new sustainable bond issuers will at some point reach its limit.

| €60bn |

New sustainable supply in euros by banks in 2023 |

That said, demand for sustainable investment alternatives will remain disproportionally high. This will incentivise banks to continue to look for possibilities to grow their green and social loan portfolios, including through the identification of new types of sustainable assets. Regulatory disclosure requirements, including those related to the EU Taxonomy, will support banks in the further identification of environmentally and/or socially sustainable assets on their balance sheet.

The offering of new types of bonds will also continue to evolve. This could include bonds issued for the purpose of financing energy transition investments or climate change adaptation solutions. However, banks may not be able to fully reap the benefits of all new opportunities in 2023 as the supporting regulation is only implemented step by step. The regulatory process regarding the development of a European Green Bonds Standard is in the end phase of policy negotiations. However, once in place it may still take time before banks feel comfortable marketing their green bonds as European green bonds.

The sustainable funding dynamics at play

Expansion of (green and social) loan books

Against the backdrop of higher yield levels and the anticipated economic slowdown, bank lending growth is set to decline. This will negatively impact the possibilities for banks to grow their portfolios of sustainable assets on their balance sheets. For instance, if house prices come under pressure, this would likely coincide with lower or negative growth of the mortgage loan balances on bank balance sheets. This may nonetheless impact energy-efficient mortgage loans less than normal mortgage loans, as a) house price declines will likely be less severe for energy-efficient houses, while b) the demand for loans financing energy-efficient houses will probably stay stronger, helped by high energy prices and regulatory developments favouring buildings with better energy performance, such as the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive.

Tagging of existing assets as green and/or social

Previous years’ growth in the market for sustainable bank bonds has largely been driven by the progress made by banks to identify eligible green and social assets on their balance sheets for the purpose of sustainable issuance. While there are many banks that have never issued a sustainable bond before, the further growth potential from newcomers will diminish. Part of these banks may simply have too small balance sheet sizes to marshal sufficient sustainable assets to (re)finance with a benchmark size green, social or sustainability bond.

The growth potential from new issuers and the tagging of assets has its boundaries

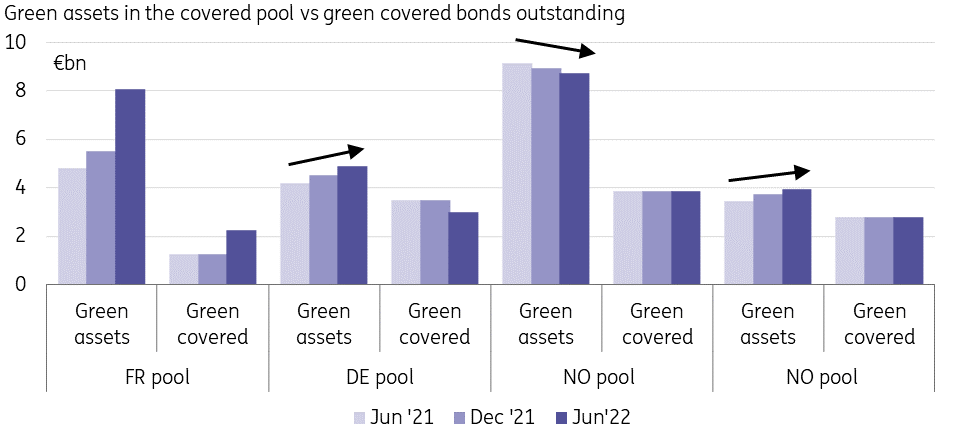

There are boundaries to the number of loans that banks can tag as sustainable. Mortgage lenders that apply a 15% best-in-class selection criterion for their green mortgage portfolios will find it difficult to identify green loans that stretch well beyond 15% of their total mortgage loan book, if this book is representative of the country’s property stock. Hence, for banks that already mostly (re)financed the identified eligible assets with sustainable bonds, the further issuance potential would have to come from fresh (sustainable) lending growth.

Cover pool data confirm that some green mortgage portfolios only grow slowly – if at all

Room left within the present portfolios of green and social assets

That said, more recent first-time issuers often have sustainable asset portfolios in place that offer scope for more sustainable bond issuance. Moreover, various banks have drafted green, social or sustainability bond frameworks that allow for the financing of multiple asset types. They have not yet always allocated bond proceeds to sustainable portfolios comprised of all these asset types. This also holds for issuers that only have a green bond framework in place and not a social bond framework, or vice versa. This indicates there is room for banks to expand their sustainable financing to other eligible types of green and social loans. Social issuance by banks could, in particular, have the potential for growth, even though the delay in Europe on the development of a social taxonomy may cause a bit of a setback.

Alternative sources of sustainable funding claim part of the available assets

Many banks offer their customers the opportunity to (short-term) invest their excess liquidity in environmentally sustainable projects via green deposits or green commercial paper. To the extent that loans in the eligible green portfolio are assigned to these money market alternatives, they cannot be earmarked anymore for green bond issuance. Besides, green and social assets are not solely refinanced through public bond issuance in the euro domain. Issuers often seek to diversify the currencies in which they issue green bonds. Some also print green notes in private placement format, which are smaller in size and require less sizeable sustainable loan portfolios. This all reduces the size of the eligible portfolios available for euro-denominated sustainable bond supply.

Refinancing of maturing green and social bonds may face stricter criteria

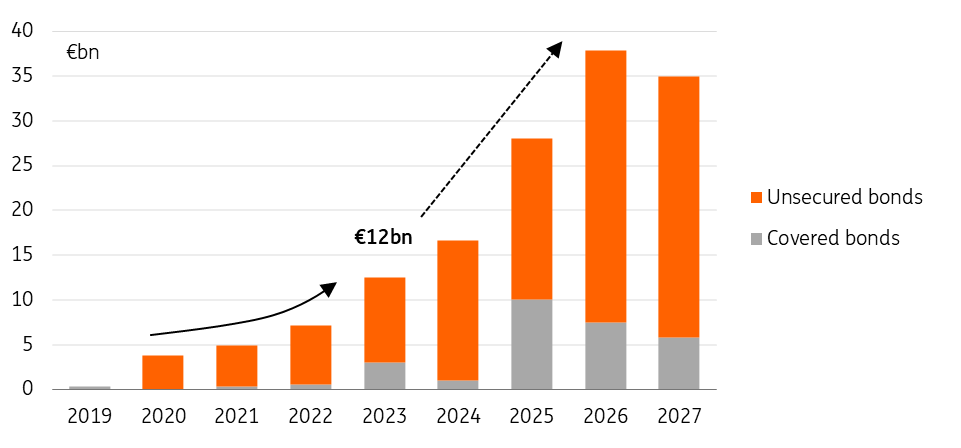

The refinancing of maturing sustainable bonds is one factor that could positively impact supply. However, while euro-sustainable bond redemptions will be higher in 2023 compared to 2022, this is still relatively low at €12bn. The bulk of sustainable bank bond maturities will start in 2025.

Refinancing of maturing sustainable bonds is just starting to pick up

| €12bn |

Sustainable euro bank bonds mature in 2023 |

Even where bonds mature well ahead of the green (or social) loans in the eligible portfolio, these loans may not all be suitable for refinancing with a new green or social bond if the eligibility criteria for green or social loans were tightened. Think for instance of green bond framework updates that aim to align the asset eligibility criteria of the green portfolio with the EU Taxonomy regulation, and/or where certain EPC labels for green mortgages are no longer eligible (such as for example EPC labels of B or C), or where the energy performance criteria for the property have otherwise been strengthened.

New growth opportunities and market developments

European Green Bond Standard – banks may not always go for gold

At the time of writing, the policy discussions between the European Commission, Council and Parliament on the voluntary European Green Bond Standard (EUGBS) were still ongoing. The European Green Bond Regulation has the ambition of setting the “gold standard” for the issuance of green bonds. To that purpose, the designation “European Green Bond” or “EuGB” can only be used to finance assets related to economic activities that meet the EU taxonomy requirements, and the transparency and economic review requirements set by the European Green Bond Regulation.

Whether all issuers will immediately go for “gold” after the European Green Bond Regulation enters into force remains to be seen, and will depend on the outcome of the substance of the final agreement. Some issuers will only gradually phase in the taxonomy compliance of their green loan portfolios. There are also countries where the NZEB definition has not yet been implemented, and for buildings built after 31 December 2020 a 15% best-in-class approach is still applied. Furthermore, issuers may not always be fully comfortable that the do not significantly harm requirements and minimum safeguards are met for all loans in the green portfolios, particularly for loans made outside the EU. They will be cautious before using the designation “European Green Bond”.

Banks may be cautious before claiming that a bond is a European Green Bond

Besides, the European Parliament favours the application of civil liability provisions towards persons responsible for any damages caused to investors due to a breach of the European Green Bond Regulation. This stretches beyond the European Commission’s proposals to include the European green bond factsheet and a statement that a bond is issued in line with the European Green Bond Regulation in the prospectus. Civil liability may make issuers more hesitant to market a bond as a European green bond.

That said, ultimately the European Green Bond Standard may still become the format most used by issuers to show the taxonomy alignment of their green bonds. Especially as investors will not always have the resources or the willingness to perform a full taxonomy compliance assessment themselves for every green bond. Besides, the ECB could at some point take the European Green Bond Standard as a reference for assigning more favourable haircuts to sustainable bonds under its collateral framework. The same will hold for the central bank’s reinvestments of redemptions of its assets purchases in the primary market. The latter would be relevant for banks if the central bank expands the decarbonisation of its asset purchases towards covered bonds.

Green TLTROs could support the growth of eligible green loan portfolios

The expiration of the ECB’s TLTRO-III operations in 2023 and 2024 will likely result in a higher capital markets’ refinancing need for banks. Due to the anticipated slower bank lending growth, it is debatable whether this will coincide with higher sustainable bond issuance. Against the backdrop of the energy crisis and the huge task at hand to make the economy more climate neutral, it is not unthinkable that the ECB will decide to establish targeted green refinancing operations. These operations could grant banks favourable borrowing conditions, but only if they grow their financing of environmentally sustainable projects.

Green TLTROs could come in favour of the issuance of green bonds as the green lending balances targeted to grow would likely be decoupled from the green TLTRO borrowings (ie there would probably not be a use of proceeds linked to such green TLTROs).

Financing of other environmental objectives – an area to explore

Green bonds issued by banks mostly (re)finance activities supporting the climate change mitigation objective. However, they could also increasingly serve the purpose of funding other environmental objectives, such as climate change adaptation. This environmental objective and its respective Taxonomy criteria have already been enshrined into EU law. Think for instance of the financing of the implementation of physical and non-physical solutions that would reduce the most important physical climate risks identified for real estate assets. The EU's Taxonomy do no significant harm criteria for climate change adaptation require climate risk and vulnerability assessments (CRVA) and an assessment of adaptation solutions to reduce the relevant physical climate risks identified. These assessments will increase the banking sector's knowledge of where such adaptation solutions may be needed.

Transition bonds could support the financing of energy efficiency improvements

The evolvement of the taxonomy classification system for significantly harmful activities will likely see new opportunities arise for the sustainable bond market. Think for instance about the financing of transitional activities. Transition bonds could help fund the upgrade of environmentally harmful activities towards intermediate performance activities, or environmentally sustainable activities.

Extending the taxonomy for significantly harmful activities

The taxonomy framework at this point solely focuses on environmentally sustainable activities (green), which meet the technical screening criteria for a substantial contribution to one of the taxonomy’s environmental objectives. However, the extended environmental taxonomy may in the future give a much broader insight into different levels of environmental performance, through a separate classification of significantly harmful activities (red) and intermediate performance activities (amber).

As a way of setting the significant harm criteria, the Platform on Sustainable Finance proposed in its March 2022 report on taxonomy extension options, to make the existing do no significant harm (DNSH) criteria fit for purpose. For instance, under the criteria for not doing significant harm to the climate change mitigation objective, buildings built after 31 December 2020 could then possibly be considered significantly harmful if their primary energy demand (PED) fails to meet the threshold for nearly zero-energy buildings (NZEB). Buildings built before 31 December 2020 would be significantly harmful if they are in the energy performance class (EPC) of D or lower, or, alternatively, do not belong to the top 30% of the most energy-efficient buildings.

With reference to buildings built before 31 December 2020, this criterion does differ from the definition of ‘inefficient real estate assets’ for the purpose of principal adverse impact (PAI) reporting under the SFDR, for which an EPC of C or below applies, but no top (30%) performance boundary. Real estate assets involved in the extraction, storage, transport, or manufacture of fossil fuels would classify as significantly harmful, both based on the DNSH and PAI definitions.

Regulatory initiatives, such as in the field of the EPBD, may see green assets grow

While not wanting to dismiss concerns regarding the risks for stranded assets, the proposed amendments to the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) could support the growth of transition loans and green mortgage balances in the years to come.

The proposed amendments to the EPBD support renovations and will improve the availability of EPC labels

The proposals aim to double the annual energy renovation rate by 2030. They provide for a harmonised scale of energy performance labels by 2025, with the A label representing zero emission buildings (ZEB) and G the worst performing 15%. All new buildings should be zero-emission buildings by 2030 and all existing buildings by 2050. To this purpose existing residential buildings should by 2030 at least be in energy performance class F and by 2033 be at least energy performance class E, and so on until the buildings are class A by 2050. Banks could finance these renovations through renovation loans. Where a renovation would morph a building to the EPC label A category this would even make the total outstanding loan balance (old and renovation) funding the building taxonomy compliant.

Moreover, in several countries, EPC labels are not available or only available to a limited extent. The proposed amendments to the EPBD may improve the availability of EPC labels. The proposals extend the obligation to have an energy performance certificate to buildings undergoing a major renovation and to buildings for which the rental contract is renewed. Buildings offered for sale or rent must have an EPC label. Besides, all member states should have a national database for energy performance certificates, that is publicly accessible. This should support the possibilities for banks to identify (new) loans on their balance sheets with a sufficiently high EPC label for inclusion in their green portfolios.

Sustainability linked… what?

Sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) are still shunned by banks

The issuance of sustainability-linked bonds is still not really taking off in the banking segment. Thus far only one bank printed a EUR sustainability-linked preferred senior unsecured note, with a reduction of the carbon intensity of the bank’s loan portfolio as a sustainability performance target. This contrasts sharply with the corporates segment, where nowadays about a third of the sustainable bond supply is in SLB format. The proceeds of sustainability-linked bonds are used by issuers for general purposes, but the characteristics of the bond (such as the coupon) can vary depending on whether the issuer meets its predefined ESG performance targets. However, coupon step-up features may be seen as an incentive to early redeem the bond. This makes it difficult to issue senior unsecured or subordinated bonds in SLB format eligible for a bank’s minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities (MREL).

SLBs may serve the purpose of underscoring a bank’s net zero ambitions

SLB issuance is also more difficult for banks than for corporates because the performance targets are not related to their own GHG emissions. Instead, they are dependent on the carbon footprint and transition efforts of the bank’s counterparties. That said, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDD) will likely require (non-)financial companies to disclose their plans on how the align their business strategies and operations with (at least) the 1.5° C global warming target from the Paris agreement. Many banks have also committed to aligning their lending portfolios with net-zero emissions by 2050 as part of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance. The issuance of sustainability-linked bonds could serve the purpose of reinforcing this ambition. Instead of using a coupon step-up feature, banks could apply alternative financial or structural consequences if the key performance target is not met, such as a donation to a charity organisation. A better alternative would be to make use of corrective action plans ensuring that issuers do take timely action if needed to reach their ESG performance target. Particularly for investment funds classified as Article 9 (Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR)) that have sustainable investments as their main objective, a step coupon reward will likely be less important than the issuer meeting its target.

Sustainability-linked financing with use of proceeds bonds

In September 2022, one of the major Nordic banks combined the best of two worlds (use of proceeds and sustainability-linked financing) by issuing the first bond ever (in SEK) financing of a portfolio of sustainability-linked loans to companies with sufficiently ambitious climate change mitigation performance goals. The structure was inspired by the ICMA’s green bond principles and sustainability-linked loan principles, without claiming alignment with them.

The bonds are issued as use of proceeds instruments. Hence, for MREL paper issued under the issuer’s sustainability loan funding framework there would be no doubts about their availability to absorb losses if needed. While the sustainability-linked loans do have interest rate step-up or step-down features depending on whether the sustainability key performance indicators (KPIs) are met, the bonds financing these loans do not have such features. Non-compliant loans that fail to meet the relevant target will be removed from the eligible portfolio (SLL funding register), even though the bank aims to always have sufficient eligible assets against the sustainability-linked loan funding outstanding.

Other banks with sufficient sustainability-linked loans on their balance sheet may also find this structure appealing to give investors the possibility to contribute to the transition efforts of the corporate clients of the bank.

Conclusion

The anticipated lower bank lending growth in 2023 could well end the growth in sustainable bank bond supply of the past years. However, for banks, there remain ample opportunities to sustainably finance the assets on their balance sheet. As many regulatory pieces of the puzzle will gradually be put in place, next year may prove a bit too early for banks to reap the benefits of all new sustainable finance potential.

Download

Download article

1 November 2022

Banks Outlook: The major challenges and opportunities for 2023 This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more