Australia: Why markets may be pricing in too much tightening

Australia’s economy is slowing, though not enough to quell inflation fears. Inflation itself is falling, though the pace of decline has been erratic and the labour market remains robust. Amidst all of this, the Reserve Bank of Australia has been hiking rates though is struggling to get its message across about the likely path from here

Guidance has sometimes been inconsistent

Markets have been taken on quite a ride in recent months. Firstly, the RBA noted at its February 2023 meeting that inflation was unlikely to fall into its target range until 2025. We don’t agree. But notwithstanding that, there seemed to be information contained in that statement that rates would stay higher for longer.

Then there was the change to the policy statement in March moving from “further rate hikes” to “further tightening”, which seemed to suggest multiple planned hikes had dwindled to just one and was followed by a pause in policy in April. Markets smelled a peak in rates at 3.6%.

Then, despite further falls in inflation, the RBA hiked again in May and held the door open to further hikes (the previous singular rate hike hint seems to have been erroneous, misinterpreted, or both), and subsequent commentary emphasised the risks to rising unit labour costs and low productivity.

That was then followed by a higher-than-anticipated wage price index for 1Q23, a softer-than-expected labour release for April, but a pickup in monthly inflation data. Markets were divided, but most thought the RBA would leave rates unchanged in June. They didn’t, and hiked to 4.1%, with a hint that further hikes were going to be data-dependent.

Most recently, the May labour data has strengthened unexpectedly again, raising doubts about the whole slowdown story and putting the RBA back under tightening pressure.

Markets are still pricing in further hikes, but it doesn’t feel like they have a strong grasp on what is really going on, or where we are going from here. Admittedly, the macro data has been very erratic. But this hasn’t been helped by official guidance, which has not been very consistent. This note will try to make some sense of what is a very cloudy backdrop. But the reality is that the outlook remains extremely uncertain.

Productivity is cyclical

The productivity/unit labour cost conundrum

Let’s start with the RBA’s assessment that depressed productivity growth and rising unit labour costs are an issue that they need to be mindful of when setting policy.

Both issues are mentioned in the text accompanying the RBA’s latest rate decision and also in Governor Philip Lowe’s 5 April speech on Monetary policy, demand and supply.

In the view of this author, productivity is a much-misused concept. It sounds real enough, but it is a construct of both economic growth and employment (whether measured as the number of jobs or hours worked). In a sense, therefore, productivity doesn’t really exist at all but is simply a residual that drops out of consideration of these other concepts. So, if you know what is happening to GDP growth, and you know what is happening to employment or hours worked, productivity measures add nothing to your understanding of the economy and are basically just a ratio of these other measures.

The same goes for unit labour costs, which can be thought of as output per unit of wages. We could write these relationships in the following simplistic way:

- Productivity = Output/Labour

- Average Wages = Wages / Labour

- Unit labour costs = Output / Wages (or re-arranged = Productivity/average wages)

And all these measures are quite cyclical. Output slows in a recession. So does employment, though it tends to lag well behind GDP and slow much later. Wages growth lags even with these changes in employment.

The result is that in an economic slowdown, productivity drops, and unit labour costs rise. And yet this is not in the slightest bit inflationary, because the overarching piece of information is that the economy is slowing, and that will lead to weaker price pressures. This is as true for Australia as it is anywhere else, where productivity has been declining as growth has slowed, and unit labour costs have risen. And we are still looking for inflation to fall.

Contributions to QoQ GDP (pp)

What is happening to growth?

So, if everything eventually boils down to economic growth, what is happening there?

The easy answer is that the Australian economy has been slowing since 2Q22. Back then, growth surged as the economy reopened, so it was a somewhat artificial surge that was never likely to last, and indeed it hasn’t. But the successively lower quarter-on-quarter growth rates that have followed have now taken growth down to just 0.2% QoQ, and year-on-year measures only still look reasonable due to a very weak base of comparison in 2022.

Not only that, but the composition of growth has seen household consumption slowing steadily, with few other elements of GDP providing much offset or promise of stronger growth in the coming quarters. Again, this isn’t hugely surprising given the amount of tightening the RBA has implemented, and the impact this is having on household debt service costs, while savings rates have also fallen sharply, making it harder for households to smooth their consumption by dipping further into savings.

One source of possible upside growth is related to China’s reopening. Though so far, this has been extremely unimpressive, with a services-led upturn having few implications for Australia’s extraction industry or manufacturing, though potentially, agricultural exports may benefit from a thawing of political tensions.

Growth looks quite likely to stay subdued at these sorts of growth rates in the coming quarters, and if so, will result in a full-year GDP growth rate of only 1.7%. Even that flatters what will be closer to a 1% annualised rate of growth on a sequential basis. And we’d characterise the risks to our forecast as being on the downside. This should help to pull inflation lower. But it may keep Australia just the right side of a recession.

Prospects for Australian inflation to keep falling

Inflation is falling, just not in a straight line

Australia introduced a monthly inflation series early this year, though many analysts still seem mistrustful of the data and even the RBA still tends to refer to the quarterly figures when talking about inflation.

Like the US, Australian inflation ticked up slightly in April, and almost exclusively because the year-on-year comparison was an unfavourable one. Changes in the CPI index on a monthly basis were little different from previous months. This uptick was as predictable as it was irrelevant. Inflation will fall more rapidly in the coming months as it is unlikely that we will see the large monthly increases that characterised global prices in the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The three-month annualised rate of inflation is a little over 4%, which equates to an average monthly increase of between 0.3% and 0.4%. Last year’s CPI index rose at a faster rate than this. So even if there is no further reduction in the current trend increases in prices, we should see inflation falling by just under one percentage point over the coming three months. That would take headline inflation down to about 5.8-5.9%.

Progress after this could be a little more pedestrian for a while. But absent a repeat of the weather/energy supply shocks of last year, inflation should decelerate forcefully again at the end of 2023 and could slow around a further 1.5pp. This should happen even without assuming any further deceleration in the current trend increase in monthly prices and would take inflation down to the mid-4% level, from which a further decline towards the top end of the RBA’s 2-3% inflation target would be in sight.

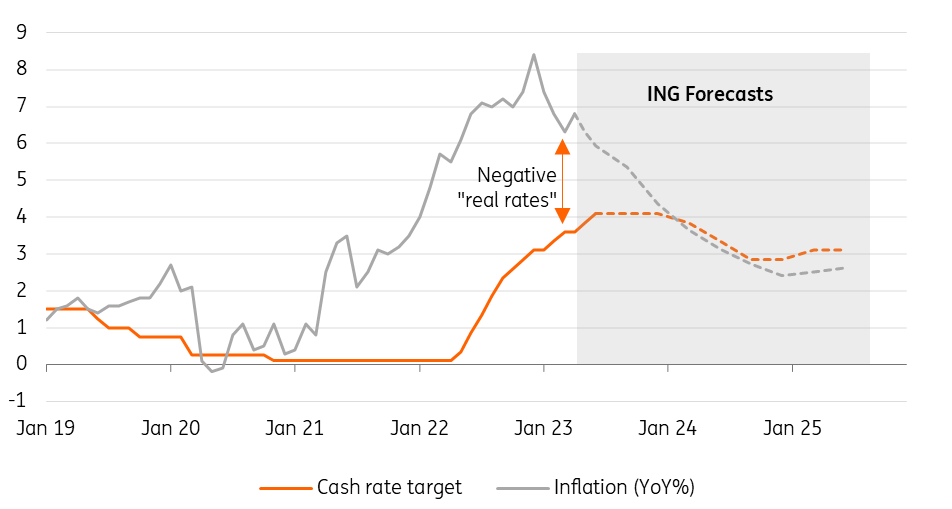

Real and nominal cash rates (%)

The case for rates having already peaked is weakening

We started by noting that markets seem confused by recent events and their pricing may reflect this. Cash rate futures point to rates rising to over 4.6% - a further 50bp of hikes.

Our view is that this is too much and that the current cash rate of 4.1% could be the peak, though this view has certainly been damaged by the latest labour report.

Our principal argument for a more moderate rate outlook is that we do expect to see inflation coming down over the coming months, and consequently, the pressure for the RBA to keep hiking will lessen substantially – especially as they aren’t expecting inflation to come down much over the coming quarters, so the hurdle for surprises on the downside is quite a low one.

Still, this isn’t likely to be plain sailing. What was once mainly a supply-side shock affecting energy and food prices has widened out to a much broader inflationary issue, with virtually all components of the CPI basket rising at a rate in excess of the RBA’s target range, and the annualised run-rate of inflation (currently about 4%) still inconsistent with getting inflation back to trend.

Further complicating the picture is the fact that despite the RBA’s tightening, house prices, which had been falling, ticked up in 1Q23. If the RBA’s tightening were sufficient to slow the economy, we would expect this to show up in housing - one of the most interest-sensitive parts of the economy. If it isn’t, then it is probably unlikely that we will see less sensitive areas, such as consumer spending dip as much as will be required for inflation to ease. That said, the house price increase seems at odds with sharply lower consumer confidence and so for now, our best guess is that the housing bump in 1Q23 was more of a blip than a concrete turn in prices. Nevertheless, a rapidly rising population, spurred by strong net inward migration as well as low housing supply could keep house prices and rents under further upward pressure. This area certainly bears close watching.

Conversely, the RBA has little interest in causing more hardship than needed in the residential property market, and will likely also be cautious about the outlook for commercial real estate should it squeeze growth too hard. Banking sector metrics look extremely solid, and delinquent and past-due loans aren’t flashing any warning signs. But as we’ve learned recently in other jurisdictions, even well-regulated financial markets are not immune to adjustment problems that are associated with monetary tightening of the scale we have seen in markets like the US, the EU, or Australia. And this, perhaps, also supports a more cautious outlook on rates than that currently priced in by markets.

Unemployment and wages (%)

Is the labour market turning? It is not at all clear

The labour market is also remaining remarkably (and unhelpfully) firm, with May data showing an unexpected rise in full-time employment and a drop in the unemployment rate. Viewed against long-run trends, the unemployment rate remains extremely low and doesn't seem consistent with slower inflation. And then there is wage growth, which is also still heading higher, though is very lagging, so we don’t really know what is going on here in real time.

So, despite the slowdown in overall economic growth, there are a number of indicators that still look like reasons for more tightening, rather than either easing or pauses, though we suspect these are not yet showing the full extent of the effects of earlier monetary tightening.

Also, the RBA has at times seemed keen not to overtighten given the lags involved in the monetary transmission mechanism. Time is likely to be a helpful ally for rate doves allowing the slowdown to work through the economy more fully. This is certainly true of the lagging labour market.

What happens in other central banks, most notably the US Federal Reserve may also play a role. It will be far easier for the RBA to hold fire if that is also what the Fed is doing. Though this also remains a tight call and the current guidance from the Fed is for another 50bp of tightening, even though we don't think that they will ultimately deliver.

All things considered, the case for believing that the cash rate may have already peaked is weakening, if not entirely dead. So while this remains the base forecast, it will not take much for us to jettison it in favour of further hikes. That said, the market expectation for a further 50bp of tightening does feel too high, and we would limit any further increase to 25bp. It would certainly help our current call a lot if activity and labour data both swung our way in the coming months, to bolster the message from lower inflation, on which we feel a much stronger conviction. We have, however, ditched our view that rates will be cut as soon as 4Q23, and have pushed this out into 2024.

AUD/USD outlook

Outlook for bond yields and the AUD

It has been a volatile 12 months for the Australian dollar, which dropped as low as 0.617 intraday against the US dollar in September 2022 and reached as high as 0.716 in February this year. Currently, the AUD is sitting in the upper half of this range. Further volatility is probable. The combination of a turn in global central bank rates, a pick-up in risk sentiment, and China’s reopening, all point to a stronger AUD in the medium term.

Still, the long-awaited weakening of the USD is proving very elusive. Global risk sentiment, as proxied by the Nasdaq, which is up more than 25% year-to-date hardly needs any further encouragement and may be due a re-think if analysts’ earnings forecasts finally start to price in recession. And China’s reopening story may prove to be a case of the dog that didn’t bark. That makes the argument for further volatility seem a stronger one than our directional preference.

We feel on stronger ground on bond yields. Australian government Treasury yields track US Treasuries closely, so the broad direction is likely to be driven by those, with local factors (RBA policy, Australian inflation etc) of second-order importance though still useful for considering the direction of spreads.

And right now, with US Treasury yields up at around 3.80%, the balance of risks for lower bond yields certainly feels better than it does for higher yields. The current spread of Australian government bond yields over US Treasuries is about 20bp, and this could widen as we think the US inflation story will improve quicker than that in Australia, resulting in a more rapid return to easing in the US.

Summary forecast table

Download

Download articleThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more