Asia’s pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic may have started here in Asia, but are there any aspects in which Asia is faring better than elsewhere? The short answer is – it depends where you look

There is no 'Asia'

Confession time...we've been deliberately provocative with the title of this note, because apart from the geographical entity, any comparison of 'Asia' with any other part of the world immediately hits the problem that, except for the economic and population dominance of China, Asia is an incredibly diverse region, with some of the biggest, smallest, richest, and poorest economies. Even culturally, it's impossible to aggregate. So what follows is a look at the performance of individual Asian economies during the pandemic. Comparing their performance with other economies in the region, and where appropriate, looking at how they are doing against non-Asian benchmarks.

So with that disclaimer out of the way, let's consider the first idea, that 'Asia' has benefited by being the first region into this pandemic, and is consequently reaping the rewards of being the first region out.

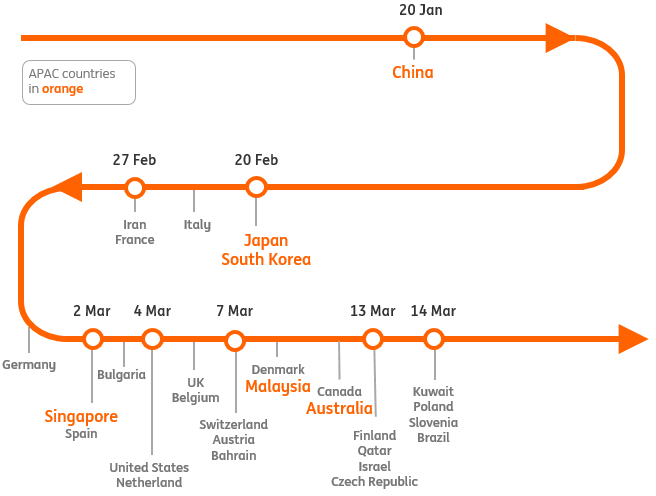

100-up - A timeline of countries reaching 100 confirmed Covid-19 cases

First in, first out?

There is some intuitive appeal to the notion of 'first-in, first-out' (FIFO) with respect to the disease outbreak, but just how well does it apply to Asia?

Certainly, this disease had its origins in China, and it quickly showed up in South Korea and in Japan, but then this concept runs into some difficulties. In the graphic below, I have ordered all of the 209 countries recording at least one Covid-19 infection according to the World Health Organisation, and then compared when each one records its first 100 cases. This helps get rid of a very long tail of countries with just a handful of cases. At about 100, one can also argue that the disease has properly rooted itself in the population. It is usually only a matter of a short time after this that 100 cases turn into several hundred, then several thousand, and so on.

There is some intuitive appeal to the notion of 'first-in, first-out' (FIFO) with respect to the disease outbreak, but just how well does it apply to Asia?

On this basis, and subject to the highly debatable quality of the data, China passed the hundred mark on 20 January, South Korea passed one hundred cases exactly a month later, the second country to do so, and Japan became the third two days later on 22 February.

But after this early start, Asia does not feature again until Singapore on 2 March, before which we have Italy, Iran, France, and Germany. Even the Singapore case is an isolated one, and the subsequent cases are all non-Asian (Spain, Bulgaria, US, Netherlands, UK). We don't get another Asian country passing this threshold until 10 March when Malaysia notched up its first 100 cases.

Of the first twenty countries to record 100 Covid-19 cases (excluding the Diamond Princess – not a country but a ship), only five are Asian, against 12 from Europe and the remainder from North America and the Middle East. So if you want to make a FIFO argument, you can do so for China, South Korea, and arguably Japan. But it really is better suited to what is happening in Europe, where new case numbers do seem to be declining.

Covid Cases % daily growth (3-day moving average)

As of 6 April, 2020

If the theory is wrong, what about the facts?

Our sample size is not large, but looking at the percentage increase/decrease in new cases (we smooth the data with a three-day moving average, but looking at the daily percentage gain based on that smoothed series) it is clear that China and Korea are doing pretty well. China, of course, has virtually no new cases, so the day-on-day comparison is close to zero. And Korea, despite the occasional cluster, is running a fairly steady daily tally, well down from its peaks, and more recently, this has seen a slight decline.

You can't make the same case for Japan though, or indeed for Singapore. Both countries were early starters. They both had very low daily counts, and in terms of total cases, are well down the rankings having been overtaken by many other countries in recent weeks. There are more than 30 countries above Japan on the leaderboard now and more than 50 above Singapore.

But despite this admirable start, whilst some countries in Europe are now beginning to show a slow and erratic downtrend in new cases, Singapore and Japan have been creeping higher. Social distancing measures have been tightened in both countries in recent days.

To put it mildly, the FIFO theory does not live up to any serious scrutiny

This is one reason we have taken the axe to our GDP forecasts for both countries, with a full-year 2020 forecast of almost -5% for Japan (assumes a further aggressive tightening of movement measures as current restrictions viewed as ineffective) and about -2.5% for Singapore.

Some latecomers to the hundred club for Covid-19 aren't doing particularly well right now, which is in line with the FIFO hypothesis. Indonesia, for example, is still on an upwards trend, though we and many others have serious misgivings about the accuracy of their data. As well as general under-reporting, Indonesia probably did not begin to register cases until quite late in the process. By all accounts, they should be doing better than they are. India, on the other hand, appeared late on the scene, so its high rate of case increase is in line with the FIFO view. That said, so were Australia and New Zealand, and they are both doing quite well.

So to put it mildly, the FIFO theory does not live up to any serious scrutiny.

Covid lockdowns

Lockdowns - do them or don't do them, just don't half do them

The experience with lockdowns may explain some of the difference in the experience of Asian countries.

Mainland China is the benchmark for aggressive lockdowns, quickly shutting down Wuhan and some other cities in Hubei province, and then doing the same in some cities in Guangdong, Zheijang and elsewhere as the disease spread. Restrictions are only just being relaxed now. So far, any second wave is confined to imported cases, but it is early days and China is worth watching closely again. It is too soon to say 'mission accomplished' in China

Korea, on the other hand, never really went into lockdown, even in the Southern city of Daegu, where the outbreak centred on a cult 'church'. They and their contacts were tested, and, where necessary, placed in quarantine. A stay-home recommendation was issued for the city, but it was not mandatory, even though it was largely adhered to. So Korea is at almost the opposite end of the spectrum to China in terms of lockdown policy. Instead, through massive testing, tracing and isolation, they managed to get their peak infections down quickly. There is still a small but persistent tail of new cases each day in Korea but it is not big enough to derail the health service or the economy, and testing continues.

Japan and Singapore both adopted measures that initially emulated the Korean approach, but with far less testing in either. This worked well in the early stages but both have now adopted more stringent social distancing measures. Singapore's could probably be described as a lockdown comparable to those in most European countries, while Japan's is still quite half-hearted.

What our casual investigation reveals is if you do a lockdown, and take the economic hit from doing so (and it is a substantial hit) then there is no point going in half-hearted

Most other countries in the region have adopted lockdowns of varying intensities, and at differing speeds with respect to their own outbreaks. Some remain regional and unconvincing (Indonesia), others a bit late to be imposed (Malaysia) whilst Philippines, Australia, New Zealand seem to have been implemented rapidly and with an appropriate degree of severity. India’s lockdown has had the side-effect of leading to a mass exodus to the countryside, which may unintentionally spread the virus further.

We summarise some of these measures in the table below. What our casual investigation of these differing approaches seems to reveal is, if you do a lockdown, and take the economic hit from doing so (and it is a substantial hit) then there is no point going in half-hearted.

There is an alternative, test, trace, and isolate - but you have to do mass testing. Otherwise, you are really only chasing the disease, and that is a race countries do not seem able to win against this virus.

Monetary response

The monetary response has been similarly variable between countries, though in all cases, there has been some easing. High yielding economies such as India, Indonesia and the Philippines have cut rates aggressively, though in Indonesia's case, have had to do so with an eye on the weakness of the currency and bond markets, which have taken quite a pummeling.

The real heavy lifting and differentiation between markets in the Asia-Pacific region is being done by fiscal policy

This may also reflect a lack of market confidence in either their reported Covid-data (openness and full transparency seems to be rewarded, even if the news isn't good) or in their response to prevent the spread of the disease. Reserve rate requirements, in China, Philippines, India, Indonesia and elsewhere have been used to supplement rate cuts and boost liquidity, especially where currency weakness was a concern. In India's case, impaired monetary transmission channels have limited the pass-through of policy rate cuts to market lending rates.

Even the region's most hawkish central banks, Bank of Korea, Bank of Thailand and Taiwan's central bank have responded with lower rates, though their rates were in any case very low before the outbreak, and they have had very little room to respond.

The Bank of Korea has also recently indicated a willingness to engage in the outright purchase of bonds, in other words, quantitative easing, which would probably be a first for a market that is still technically considered 'emerging'. It had previously alluded to its temporary unlimited repo operations as a form of QE, which critics rightly pointed out, it wasn't.

Singapore's central bank has flattened the path of the nominal effective exchange rate and dropped its mid-point, and both the Reserve Banks of Australia and New Zealand have started quantitative easing, having slashed their official cash rates to the effective lower bound of 25 basis points.

It all looks aggressive and very helpful. But in the end, such monetary measures are probably of marginal value in this battle, where corporate and household cash flow are the primary victims. Cheap money maybe helps a little with debt service costs, but where loan moratoriums are in place, which is now often the case, even this is somewhat redundant. The real heavy lifting and differentiation between markets in the Asia-Pacific region is being done by fiscal policy.

Monetary response

Fiscal policy - rich and poor spending, but rich spending more heavily

Like elsewhere, fiscal policy is the real work-horse in terms of effective stimulus across Asia to offset the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, and it is also the main area where policy distinctions can be made across the region. But no matter how generous these support packages are (and some of them are of historic proportions), the frequent question "is it enough?" misses the point that no amount of fiscal stimulus, even when tied up with a super-accommodative monetary policy, will ever be enough to totally smooth over the cracks caused by this outbreak.

Like elsewhere, fiscal policy is the real work-horse in terms of effective stimulus across Asia to offset the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic

What is needed in huge measure, are policies to preserve jobs, to preserve businesses, and to preserve the banks that have lent to them and which will need to keep lending to them even whilst their clients' earnings dry up. That could entail massive amounts of public spending, tax cuts, wage and employment subsidies, all on a scale never previously.

Failure to do this risks a permanent loss of potential output. This is why recent rating agency decisions to downgrade the outlook for countries fully supporting their economies against this outbreak (Australia for example), could in our view be myopic. There is no sense in reining in a government deficit to keep it below some artificial target – say 3% of GDP – if in doing so, that action results in a loss of 50% of actual and potential GDP. In the case of economies with unshakeable fiscal credibility, such as Australia, such outlook downgrades can be worn as a badge of honour. Financial markets will hardly attach any value to these kinds of downgrades, but they still provide a deterrent for many emerging market economies.

This may be one of the reasons that there is often a big difference in the scale of headline fiscal support measures and the actual on-budget figures. This is illustrated in the following chart.

Take Malaysia, for example. To appeal to the sense that they are pulling out all the stops in an attempt to keep their economy afloat, their most recent fiscal package headlined at about 18% of nominal GDP. But like many emerging market countries, the actual "on-balance-sheet" total is much smaller – closer to 4% of nominal GDP.

The difference between headline and on-budget measures is a bunch of policies such as soft loans, early access to pension savings, deferred (but not cancelled) taxes and so forth. The same pattern follows for Japan, where their most recent package topped 20% of GDP, though a measure that more accurately captured the fiscal thrust of the package would be a little under 6%.

there is often a big difference in the scale of headline fiscal support measures and the actual on-budget figures

Of course, Japan has a debt-to-GDP ratio in excess of 200%, so you could argue that they have limited room to move with fiscal policy. An alternative viewpoint would be that with so much debt, a bit more wouldn't hurt. Right now, that is probably the more valid viewpoint, not just for Japan, but for all economies of the region and perhaps elsewhere.

Countries with deep pockets, Australia and Singapore show a much closer alignment between large fiscal stimulus packages and the actual thrust contained within them. Those with weaker financial positions, Malaysia, Indonesia, have had to bulk the packages out more and their genuine fiscal support is typically lower. The net result of all this will be to expose the most vulnerable economies of the region to the greatest permanent losses of potential output and condemn them to slower recoveries.

This isn't the end of the road, for fiscal stimulus, and the chart below will probably be out of date even by the time this note goes to print, as governments in countries such as Korea, where the fiscal thrust is currently relatively weak, find the courage to keep tapping their fiscal resources. It is an effort worth pursuing.

Size of fiscal boost is often exaggerated

Where does this go now?

In the preceding analysis, we have set out a comparison of the approaches taken to Covid-19 by the countries of Asia. And we have shown these to be widely differing across a variety of important parameters, including not just the response to the outbreak itself, but also in the palliative monetary and fiscal measures set out to combat the impacts of the pandemic on the economy.

There is a long way to go, and these conclusions are tentative at best, and could yet change

Despite the widely varying responses, with few exceptions, 2020 is heading towards being one of the worst, if not the worst ever year for economic growth for most of the countries considered. And that conclusion includes comparisons with the Asian debt crisis and the global financial crisis. That can't be helped. The real prize for countries now is to ensure that the recovery, when it comes, and eventually it will come, will be as strong as possible. And that will favour those economies that combined an effective virus containment method - whether this was "test, trace, isolate", or aggressive "lockdown", combined with massive (mainly fiscal) efforts to support and protect business to survive long enough to see the upturn when it comes.

With very different approaches to the pandemic, China, and Australia (arguably also New Zealand) look well placed for a 2021 recovery. Korea has dealt with its outbreak efficiently, but falls short of the fiscal support offered elsewhere, but should do OK. And Singapore had a good start and will probably cope with the recent slippage on new cases given its very strong fiscal support. Within other SE Asia, the Philippines probably has the edge over its other regional peers on an overall assessment of outbreak containment and official support.

There is, however, a long way to go, and these conclusions are tentative at best, and could yet change.

Download

Download article

14 April 2020

Good MornING Asia - 14 April 2020 This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more