Asia: What went wrong in India?

While there is a narrative that talks about double mutations and Indian variants, mass rallies, sporting events and religious festivals probably also played a significant part in the recent acceleration of cases in India. There are very clear lessons to be drawn from this. India may be looking at another lost year for the economy

An important lesson - and not just for India

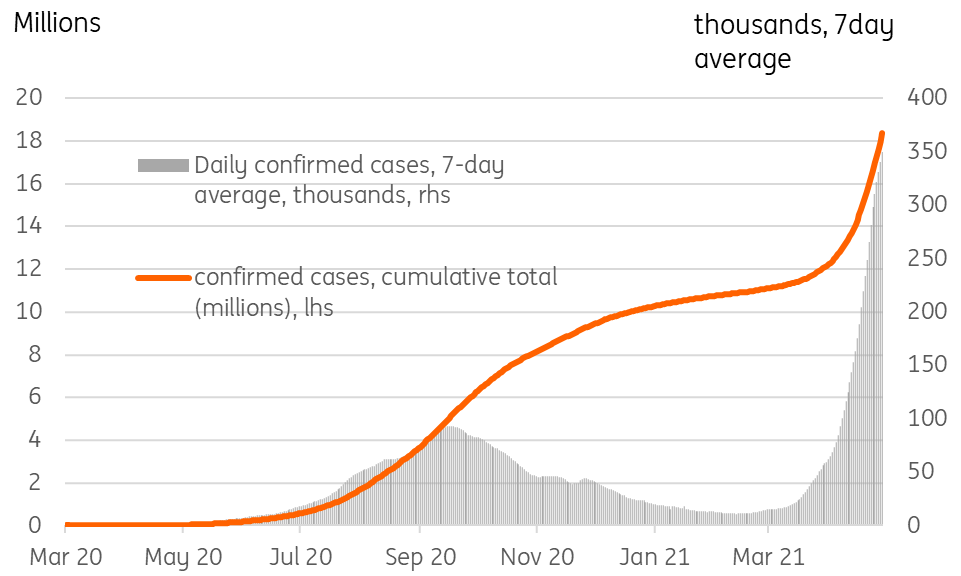

Only two months ago, India’s Covid-19 case numbers were fluctuating somewhere around 10,000 per day. That was substantially lower than many European countries, and with a population of about 1.3 billion, looked a manageable situation.

Today, the figure is closer to 400,000 cases per day and rising rapidly. Three questions worth asking are:

- What went wrong?

- Could this happen elsewhere (and not just in Asia)?

- What does mean for the Indian and global economy?

Indian Covid-19 cases

So what did go wrong?

There is a lot of talk about the new Indian variant, the so-called B1.617 strain of Covid-19, as the major factor driving the recent acceleration in new cases and deaths in India. And a number of journalists have been equating additional mutations (double mutations in this case) to greater infectiousness and greater morbidity.

The scientific community is still assessing the data on this new variant, but the evidence supporting the hypotheses above is mixed as are opinions on the matter. Appealingly, the narrative for the new variant hypothesis shifts some of the blame for the outbreak to viral mutations that could not perhaps have been anticipated or prevented. Relative to the number of infections, there has not been a lot of genomic sequencing in India according to some reports. Some reports note that in Maharashtra (one of the worst affected regions), in early April, the B.1.617 variant accounted for only about 15-20% of new cases, though this has most likely risen since then. In other regions (Punjab for example), the UK B.1.1.7 variant was the more prevalent.

What is known, is that this variant has been present in India since late last year. If it was the major factor of the recent spike, like the UK B1.1.7 variant in parts of Europe (and India), some scientists suggest that it would probably have surged before now.

For a population the size of India’s, this makes total vaccination unlikely until mid-2022 and in the meantime, leaves it hugely vulnerable to waves like this.

So if the new variant cannot be ruled in or out as the main cause, what else might be a factor? One possibility might possibly be human actions.

Those of you who, like me, love cricket, may remember the England-India cricket tour at the beginning of February with test matches and T-20 games in Chennai and Ahmedabad, followed by one-day internationals in Pune. More ominous than even the spin-friendly crumbly pitch surfaces was the presence of large, frequently maskless crowds. Spectators were only stopped from 15 March as cases began to rise.

Then, state elections in West Bengal, Assam, Kerala and Tamil Nadu led to large scale political rallies. Lots of people, lots of shouting of slogans, minimal social distancing.

And in addition, the Kumbh Mela religious festival, famous for the millions of attendees over several weeks provided yet another potential infection super-spreading event.

Common to all of these events, whether sporting, political, or religious, was a lack of social distancing, and frequently, a lack of mask-wearing.

It also doesn’t help that India’s vaccine rollout is not going particularly fast. At about 10 vaccinations for every 100 people currently, India is not the worst in Asia by any stretch, and as a major global producer of vaccines, it has some advantages over some of its neighbours. But from daily vaccinations in excess of 4 million, the daily vaccination tally has recently halved to a little over 2 million. For a population the size of India’s, this makes total vaccination unlikely until mid-2022 and in the meantime, leaves it hugely vulnerable to waves like this.

Events that may have accelerated India's Covid-19 spread

Could this happen elsewhere?

The short answer is a resounding “Yes!”. Throughout this pandemic, governments have demonstrated a form of pseudo-scientific nationalism, that has discounted Covid-19 lessons learned from geographic neighbours. “This won’t happen to us” or “we’re different” are views that have been proven wrong time and time again.

With much of Asia having had a fairly light version of the pandemic, the economies of the region are now relatively open. Mask wearing is common, but social restrictions are less onerous than in some other parts of the world. Were there really to be a highly infectious and deadly variant of the Covid-19 virus circulating, it might not take long for it to spread through these populations. Relatively few countries in Asia are substantially better vaccinated than India, and many of them far less.

The slow speed with which many countries shut down travel access with India once India's Covid-19 case numbers began to surge, demonstrates once again that governments in the region and elsewhere are still trying to find a trade-off between economic openness and viral containment. What India demonstrates very amply, is, there is no trade-off beyond a few weeks.

Vaccinations per 100 population as at 2 May, 2021

Economic impacts

We already had an economic outlook for India that was substantially below consensus (see our latest country deep-dive by Prakash Sakpal). But even that now looks challenged in the light of unfurling events. Lockdowns are once again being imposed across the country. In time, they will bring down daily cases and hopefully enable India’s overwhelmed medical system to cope once more.

But a downside scenario could see India making zero economic progress this year, after the nearly 10% decline in 2020. In terms of the size of the economy, India is the sixth-largest economy in the world. Though in practice, this means that it is only slightly larger than the economy of the UK. At the beginning of the year, India was expected by much of the consensus forecasting community to grow at close to, or above, 10% this year (though base effects are at work in India as everywhere else), so the potential loss of that 10% of growth is about twice as significant as it would be if the UK were to drag sideways this year instead of bouncing as expected.

At the moment, India’s prospective economic weakness looks likely to mainly cap oil price increases, rather than to cause them to fall

This could still have impacts on commodity prices. India is the world’s third-largest importer of oil, and at about 4.5m b/d of imported oil, accounts for about 10% of all crude oil trade. Currently, oil prices are being dominated by the strength of recovery elsewhere, in particular the US. So at the moment, India’s prospective economic weakness looks likely to mainly cap oil price increases, rather than to cause them to fall.

India is also the world’s second-largest importer of thermal coal, accounting for about 17% of global trade in this commodity, from suppliers like South Africa, Indonesia, and increasingly, Australia (thanks to China’s unofficial ban). India is also the world’s fourth-largest importer of LNG and the second-largest consumer of gold. In 2020, Indian gold demand declined by 35% as a result of Covid-19. At the very least, India's economic problems will take some of the air out of currently very buoyant commodity markets.

Locally, the disruption of the economy by this current wave of infections is leading to price increases, and the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) 4-6% target range for inflation looks in clear danger of being exceeded. While some see this as an argument for the RBI to tighten policy, we see the opposite as far more likely, with a possibility of a sympathy-based 25bp cut. Not that we think rate cuts will do an awful lot of good, but they won’t make matters worse, whereas rate hikes will.

Further fiscal support is also inevitable and India has thus far not been too generous in this regard, aiming most of its fiscal firepower in 2020 at longer-term structural measures – not unhelpful, but perhaps not the emergency support that is needed in times of acute economic stress like right now.

Elsewhere in the region, and also in other parts of the world, such as the Middle East, Indian migrant labour has been a source of cheap labour for decades. But with borders now closed indefinitely, such labour flows will be shut for the foreseeable future. Other sources of labour will need to be located for industries like construction, and these may well be more expensive, adding to the global reflation/inflation story.

Fortunately, India is less critical for global supply chains than China, for example, with its weaker manufacturing base and greater emphasis on the service sector such as outsourced IT support. It’s too early to say that globally outsourced service activity like this will not be affected. Clearly, a lot more of such activity can be done from home these days in the event of prolonged lockdowns, but we can’t rule out some disruption.

For manufacturing, India was previously looking like a major beneficiary of supply-chain relocation following the trade and technology war between the US and China in recent years. That no longer seems as likely. At least not until the current crisis has passed.

Ironically, one of the main industries in which India operates on a global scale, is pharmaceuticals and life sciences, including vaccines. It is inevitable that more of this locally produced output is diverted for domestic needs in the short term, though this may lead to shortages in supply elsewhere in the world. Right now, India’s need is clearly greater than anywhere else, and we would hope that any political fallout from this would be minimal.

Another industry that may suffer is the telecoms industry. India has more than 670 million internet users and is the second-largest global market for smartphones. With increasing local production, that can also be expected to falter in the short term, as people’s incomes are undermined by the pandemic and shutdowns.

This could happen to you

Summing up, irrespective of the role of any new variants in India’s current situation, India’s problems could happen to any country that lets its guard down with respect to social distancing before adequately vaccinating its population. A missed year for economic growth, if that is what we are facing, would be significant for India, but with global growth elsewhere bouncing back hard, it is likely that India's stagnation will be absorbed without too many global ramifications.

Likewise, India’s relatively light manufacturing industry means it is not as central to global supply chains as many other Asian economies would be, though where it is, pharmaceuticals and life sciences, it may lead to shortages in exactly the areas in which there is the greatest demand.

Download

Download article7 May 2021

Someone left the cake out in the rain… This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more