Another month of political uncertainty for Argentina

Weekend presidential election results in Argentina have defied the August primaries, with Peronist economy minister Sergio Massa leading with 37% of the vote. The front-runner from the primaries, libertarian Javier Milei, has come in second with 30%. The pair will enter into a run-off on 19 November

Surprise lead for Sergio Massa

The results of Argentina's presidential election have come as something of a surprise given Javier Milei's big win in the August primaries. Most local commentators seem to suggest that the electorate was not quite ready for the brand of anarcho-capitalism that Milei's libertarian party was prepared to introduce. It included dollarising the economy, scrapping the central bank, and cutting back heavily on government spending in an effort to break the cycle of hyperinflation, devaluation, and default which are so common in Argentina.

While the current economy minister Sergio Massa has won a much higher-than-expected 37% of the vote, it is still short of the 45% required to deliver a first-round win. The run-off takes place on 19 November, with the new administration taking office on 10 December. The challenge over the next month will be for Massa and Milei to sell themselves to the 33% of the electorate that did not vote for them. In focus will be the votes of the centre-right candidate, Patricia Bullrich, who secured 24% support at the weekend.

The result of the run-off in November still seems very much open. Presumably, Sergio Massa will continue his strategy of social support and looser fiscal policy which has tended to see most of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) fiscal targets being missed. Equally, Javier Milei will continue to showcase the dire state of the economy under Massa's stewardship and demand a sea change in Argentina's economic policy.

It is not quite yet clear whether the Argentine electorate is ready for a brave new world, but much uncertainty over the next month – along with neither candidate showing much love for the beleaguered peso – will likely keep Argentine assets under pressure.

Below, we take a look at the challenges facing the Argentine economy for whoever wins in November.

Macro challenges mean tough choices lie ahead after election

Argentina’s macro challenges appear enormous regardless of its government and have only grown in recent years, despite securing a sovereign debt restructuring agreement with bondholders after defaulting in 2020. The country is stuck in a vicious cycle of soaring inflation and FX depreciation, with the central bank required to intervene in the currency market to avoid excessive currency weakness while also providing monetary financing for the fiscal deficit. Somewhat understandably, consumer and business confidence remain depressed, with a deep recession expected for 2023.

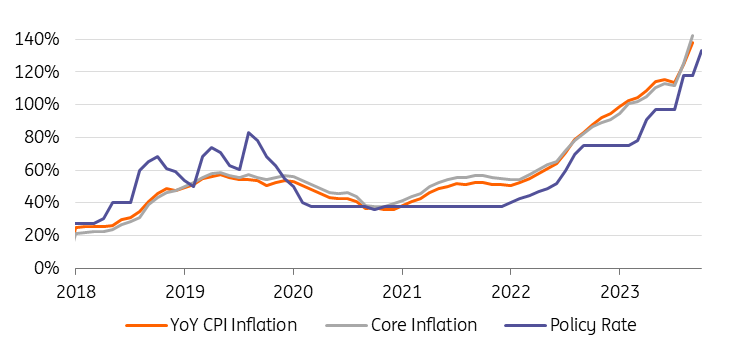

In this context, inflation looks to be spiralling out of control, surging beyond 100% on a year-on-year basis and rising for much of this year. The central bank is significantly constrained in its policy response. Despite hiking interest rates multiple times this year to 133%, they remain in negative territory on a real basis (compared to realised inflation), as positive real rates would impose an even greater fiscal cost on the government and the central bank itself through debt financing needs.

Argentina inflation and policy rate

At the same time, these negative real rates increase the pressure on Argentina’s external position, eroding demand for the peso and driving capital flight into dollars by residents. An unprecedented drought has only worsened the situation, cutting the harvest and therefore export earnings from vital corn and soy crops. This has brought the nation’s current account back into deficit from a few years of surplus, a further source of pressure on the external position and currency.

To cope with this pressure, the central bank has been forced to intervene more actively, selling its already scarce FX reserves to defend the currency. Gross FX reserves have already fallen below $30 billion from over $70 billion in 2019, while the net position (in grey below, netting off banks’ FX reserve requirements and the central bank’s FX swap liabilities) is even more concerning, in negative territory by most measures and pointing to even more limited firepower available to fight off depreciation pressures.

Gross and net FX reserves

IMF remains a major factor

Given Argentina’s significant external financing needs, dwindling FX reserves and limited prospect of returning to international bond markets anytime soon, the nation’s official lending sources have been brought into sharp focus. Support from unorthodox sources, such as a swap line from China, has offered a short-term boost, but relations with the IMF remain a key factor. Argentina is the IMF’s largest debtor after an unsuccessful $57 billion loan package was agreed and partially disbursed in 2018. Both parties now appear somewhat reliant on each other with the need to roll over the Fund’s exposure despite the nation continuously failing to meet programme targets and ongoing doubts about debt sustainability.

In 2022, a new deal was reached with Argentina to essentially refinance its outstanding IMF debts, but even this renewed deal has been regularly held up by delays to reforms and disappointing economic data outturns, in part impacted by the external shock of drought. The latest tranche of $7.5 billion was paid in August, and yuan from a swap deal with China was used to make an IMF repayment over the summer – but further tough negotiations with the IMF will likely await a new government given the persistent disappointments over the nation’s reform progress and deepening economic crisis.

IMF lending to Argentina

The IMF, however, will not be the only interested creditor in the ongoing political uncertainty. Along with significant IMF repayments for the Argentine government over the coming years, Eurobond payments to international bondholders will soon step up through coupon and principal amortisation as the period of relief offered by 2020’s restructuring deal runs out. This is only going to add to Argentina’s problems in the coming years, with the prospects for rolling over these liabilities in the international market low and alternative financing sources increasingly scarce.

Sovereign FX debt repayments

This situation is clearly reflected in the Eurobond market, with Argentina’s international dollar bonds still priced in highly distressed territory – on average below 30c on the dollar over three years since completing a debt restructuring. This is a signal that in no uncertain terms points to investor expectations for yet another debt default and restructuring. The question remains as to whether official creditors, such as the IMF or any bilateral lenders, would be willing to write off any amount of debt alongside bondholders.

Argentina sovereign dollar bond price (cents on the dollar, average)

Fiscal reforms hold the key

Amid this gloomy outlook, fiscal policy is one area that the incoming government is likely to focus on and could offer a path out of the current crisis. Significant spending cuts – and therefore a shift to a primary surplus for the government – would be beneficial in reducing inflationary pressures, domestic demand for imports, along with the need for central bank monetary financing. Of course, this is easier said than done. The incumbent government has consistently failed to meet the IMF’s targets for the primary deficit and has seen limited progress in fiscal consolidation. Spending cuts remain a politically sensitive issue, in particular for a country already suffering from such economic hardship that could see activity further depressed by a bout of austerity.

Public sector balance - % of GDP, rolling 4Q

Meanwhile, Argentina is likely to remain vulnerable to external shocks. Government debt at over 80% of GDP remains well above pre-2018 levels and looks too large for the economy to handle, despite falling from over 100% in 2020. The large share of foreign currency debt significantly increases this vulnerability, with the expected further depreciation of the peso likely to increase the government’s debt burden, as seen in 2018.

Government debt (% of GDP)

Dollarisation: An effective commitment device

Hyperinflation in Argentina has kept the Argentine peso under massive pressure, as it would in any given economy. The FX stability of the 1991-2001 Convertibility regime is a distant memory, and this year has seen the official Argentine peso exchange rate devalue 50% against the dollar as the ability of Argentine authorities to control the peso’s slide has weakened. In fact, Argentina’s net FX reserves stood at around negative $10 billion in late summer, where its gross reserves were outweighed by the central bank’s liabilities of swap lines and FX deposits.

The official rate’s 50% devaluation this year compares to the 60% loss of the unofficial ‘blue’ USD/ARS rate and the near 80% devaluation now priced in by the Argentine Non-Deliverable Forward (NDF) market. One can argue that the NDF market merely represents market demand for FX hedging rather than a reliable future guide for USD/ARS. But nonetheless, peso-selling interest understandably dominates this NDF market. Incidentally, it seems that Argentina’s central bank typically tries to intervene in all three of these FX markets, but clearly lacks the means for success.

Argentina's multiple exchange rates

It is against this background that Javier Milei’s pick for central bank governor, Emilio Ocampo, has put forward his plans for the dollarisation of the Argentine economy – or the use of the dollar as legal tender. Behind that proposal lies an inherent mistrust of Argentine institutions – the belief that the central bank should be abolished, for instance – and the view that dollarisation would reflect an ‘Effective Commitment Device’ (ECD). The idea here is that an ECD is needed to show that Argentina is serious about change after the many policy flip-flops over prior decades.

The objective of dollarisation would be to bring down inflation and remove the overused emergency lever of devaluation to support growth. Proponents put forward the success of Ecuador’s dollarisation in 2000. Equally, critics would say dollarisation is not irreversible, and having experimented with it for a decade, Zimbabwe’s re-introduction of a local currency in 2019 quickly resulted in renewed hyperinflation. Those critics also argue that a G20 economy like Argentina is too large and diversified an economy to follow the likes of Ecuador, Panama, and El Salvador into dollarisation.

The arguments for and against dollarisation get rather technical pretty quickly. For example, where does Argentina get the $50-60 billion dollars it needs to buy out the peso money supply? Details on this are not obvious, although it does look like Argentina might have to issue more USD debt or undertake some very clever financial engineering to fulfil its goals. And at what USD/ARS exchange rate would the dollarisation take place? Ecuador’s sucre went through major devaluations before the final USD/ECS exchange rate was set at 25,000. The working presumption might be that dollarisation in Argentina could occur at USD/ARS 900/1000, around the current blue market rate. Though of course, this market rate could change considerably before the new administration takes control in December.

What seems clear, however, is that for credible dollarisation to take place, it would have to be backed up with strong and credible fiscal guarantees. Dollarisation might remove the risk of a currency devaluation, but it does not remove the risk of sovereign default – the latter only too familiar to Argentina.

Dollarisation might remove the risk of a currency devaluation, but it does not remove the risk of sovereign default

Clearly, many more pieces of the puzzle need to fall into place in this story. But something does need to change. We say this because many multi-national corporates with interests in Argentina are struggling with the hyperinflation environment and hyperinflation accounting rules which force them to take balance sheet losses on the Argentine operations through their Profit and Loss accounts.

It would seem to be in everyone's interests if a credible exchange rate system backed by a strong fiscal position could be employed as soon as possible. Most seem to think that dollarisation could not see the light of day since any Milei administration would lack the support in the Chamber of Deputies to advance this policy. Yet, the alternatives of what the IMF calls Argentina’s Multiple Currency Practices (MCPs) hardly look any more encouraging.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more