UK unemployment rate surpasses pre-Covid lows as shortages persist

The UK jobs market is undeniably hot right now, but that could change. The Bank of England has forecast higher unemployment, although much obviously depends on whether we see a more severe economic downturn. Barring that, the potential for ongoing worker shortages probably means there's a strong incentive for firms to avoid layoffs

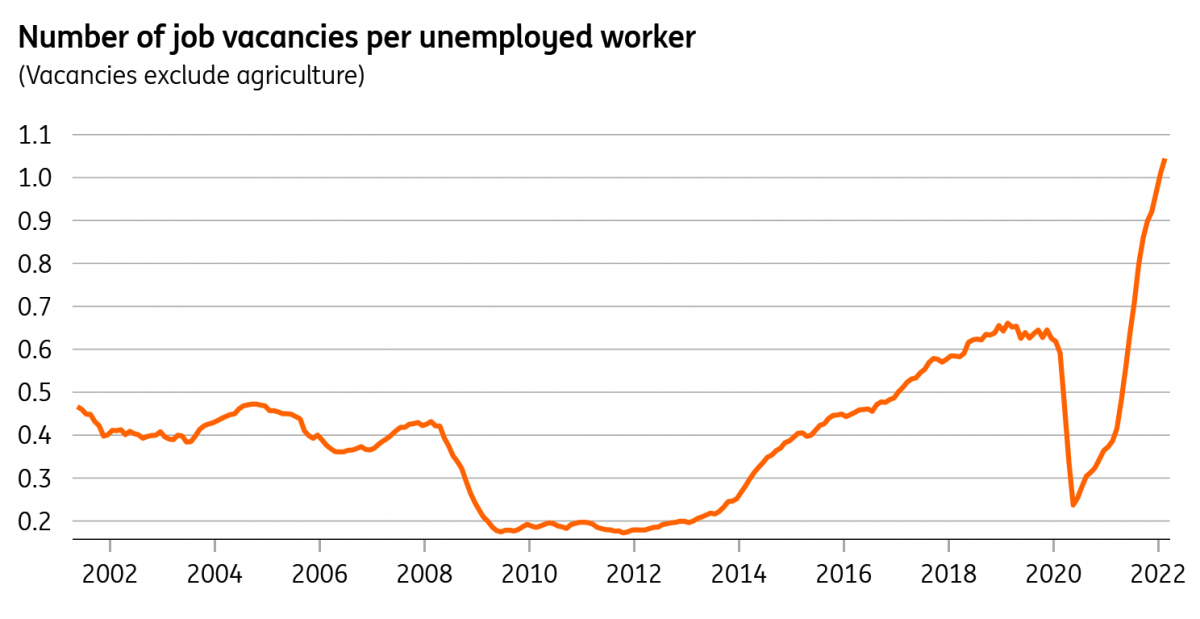

For now, at least, the UK jobs market looks pretty hot. The unemployment rate, at 3.7%, has now surpassed its pre-virus lows, and there’s more than one job vacancy for every unemployed worker. Last month was the first time that had happened in the 20 years that data is available. Solid hiring demand and a lack of workers means wage growth is running a little faster than it was pre-pandemic, while the Bank of England’s latest survey shows that most firms feel able to pass these costs on.

Of course, the big risk now is that this story begins to change. In a less-than-subtle message to investors, the Bank of England recently forecast that the unemployment rate could rise above 5% again over the next couple of years – a signal that market pricing on rate hikes has gone too far.

There's now one vacancy per unemployed worker in the UK

Whether that forecast comes to pass will heavily depend on how quickly and how far the recent labour shortages ease. We subscribe to the view that shortages have been exacerbated by a post-pandemic staffing mismatch as well as the rapid return of hiring appetite through the second half of last year. For instance, the huge change in consumer spending patterns without the corresponding shift of workers between sectors has helped create pockets of pressure. Hiring challenges in logistics, a symptom of the abrupt switch to online retail, is an obvious example. This should start to improve now that spending patterns are rebalancing.

Nevertheless, some causes of the shortages appear to be more deep-rooted. Like the US, the issue has been amplified by abnormally large outflows from the jobs market into inactivity – that is, not actively searching for employment. Early retirement has played a role, and indeed the change in participation is most apparent in older workers.

But long-term sickness is increasingly cited as a core issue – and while it’s tempting to conclude that this is due to long Covid, it’s still unclear whether that’s what the data is telling us. If nothing else, this challenges the idea that higher inflation will lead to a more rapid return of workers to the jobs market.

A lack of inward migration is also a challenge, and the number of EU nationals in UK employment is down by almost 5% since the start of the pandemic, particularly in consumer services. Hospitality saw a 25% reduction in EU nationals as payrolled employees between June 2019 and 2021, and that probably helps explain why food prep/service remains a key source of wage pressure according to Indeed hiring data. Around a fifth of large businesses recently cited a lack of EU applicants as playing a role in worker shortages.

The number of EU nationals working in the UK has fallen during Covid

Put another way, worker shortages are likely to remain an issue for businesses. And that suggests there’s a big incentive for firms to hold onto staff even if demand falters, amid concerns that they might not be able to rehire easily. In other words, for the Bank of England’s higher unemployment rate forecast to come to pass, we would probably need to see a more severe downturn (as opposed to stagnation) in UK activity where firms are forced to cut staff.

Nevertheless, firms' margins are going to come under increasing pressure amid lower consumer spending appetite and external cost inflation. So even if employment stays supported, we suspect we’ll still see some of the impetus behind wage growth fade. This underscores the message from the BoE that it probably won’t need to hike too much further over the coming months.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download snap