Hungarian labour market slack absorbed

The latest data suggests that the Coronavirus-induced slack in the labour market has already been absorbed. Corporates are facing labour shortages, providing further cost pressures and increasing the chance of stronger wage-push inflation

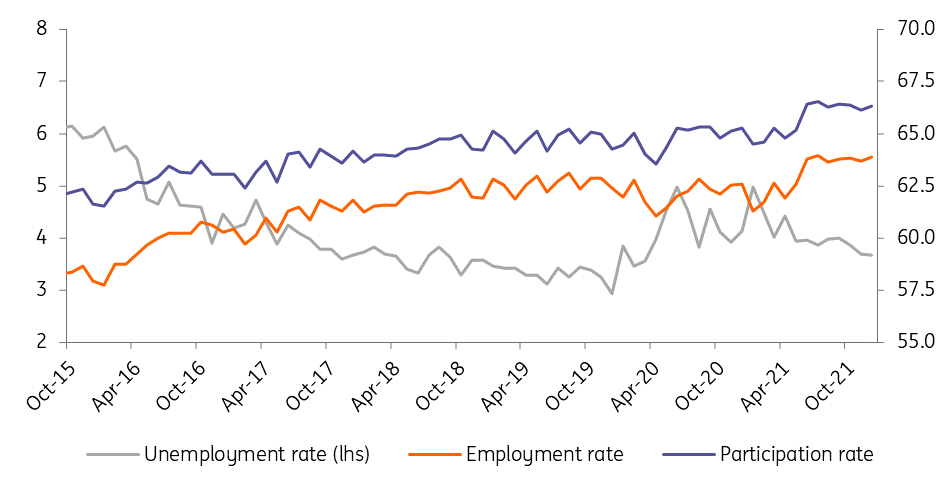

Labour market indicators used to lag other major economic activity indicators, such as gross domestic product (GDP) growth. In the rebound period after a crisis, the labour market would be the last area where we could see any signs of improvement. Only 18 months have passed since the unemployment rate surged to a record high during the Covid-19 crisis (in June 2020), but the Hungarian labour market seems to be back at full strength.

The December 2021 unemployment rate came in at 3.7%, which means approximately 180,000 people are officially unemployed. The year-end figure roughly matches the November data. The same applies to both the participation and employment rate. The labour market may have reached a resting point, suggesting that the crisis-induced slack has already been absorbed.

Labour market trends (%)

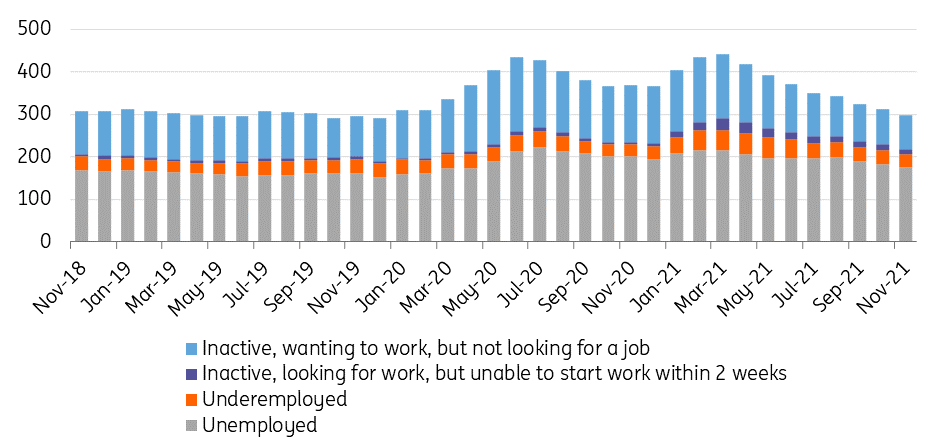

Some may argue that the pre-crisis unemployment rate was lower, therefore there was room for improvement. In our view, as both the participation and employment rates have been practically unchanged since the second half of 2021, the only source of improvement could come from the recent pool of labour reserve. Unfortunately, the quality of this pool is getting poorer. The share of long-term unemployed (those who are without a job for at least 12 months) among the group of unemployed is back at 34%, matching the figure seen in early 2019. The potential labour reserve is now back below 300,000, close to the all-time low.

Potential labour reserve ('000, 3-m moving average)

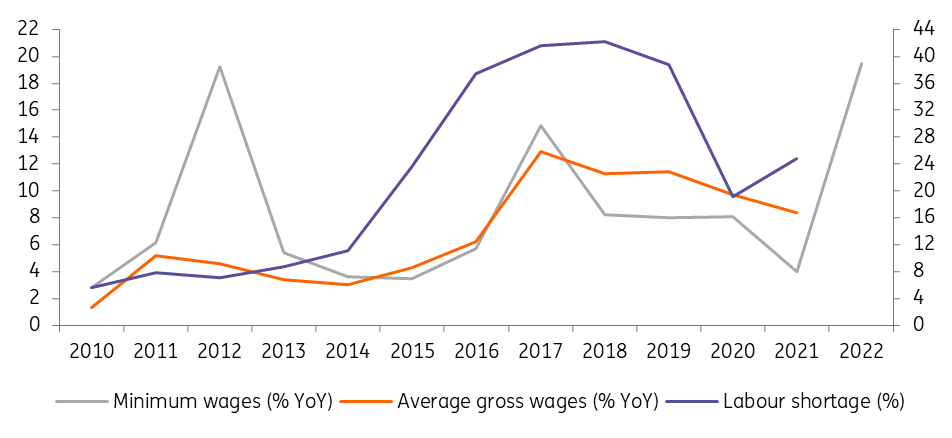

Based on a recent Eurostat survey, which measures the share of companies complaining about the lack of labour, we can say that the labour shortage in Hungary is increasing rapidly. In 4Q21, more than 30% of the companies were limited by labour shortages, matching the ratio at the end of 2019.

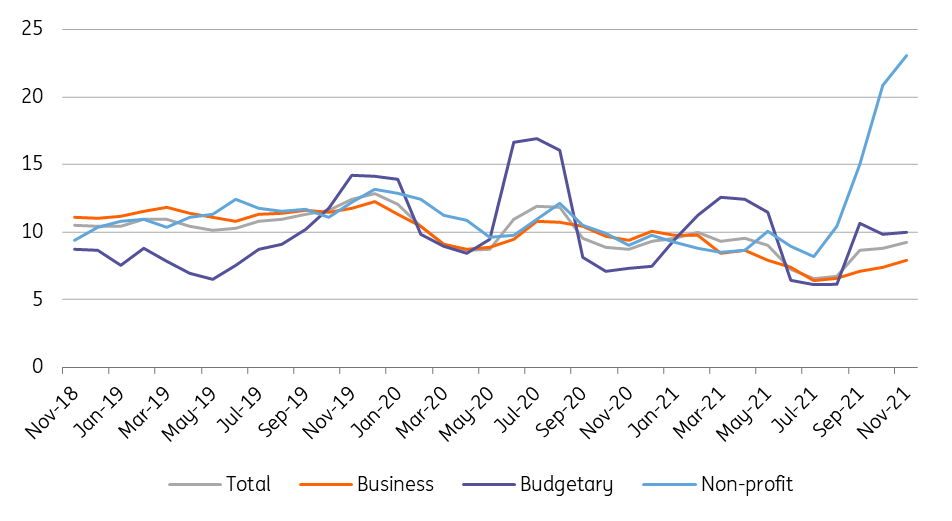

In such an environment, we wouldn’t be shocked if 2022 wage growth was fuelled by the labour shortage. This impact will be complemented by the 20% minimum wage increase both for skilled and unskilled labour. The November wage growth came in above expectations, showing a 10.1% Year-on-Year gross and net wage increase. Regular wages moved up by only 8.7% YoY, so bonus payments were much stronger than a year ago, which looks realistic as Hungary probably produced record-high GDP growth in 2021.

Wage dynamics (3-month moving average, % YoY)

The significant increase in average earnings in the non-profit sector was due to the fact that from the beginning of August many educational institutions, having previously been publicly funded, were included in this sector.

But even this strong nominal wage growth means nothing (or at least much less) if inflation soars. The Statistical Office calculated a 2.5% YoY real net wage increase in November 2021. Workers are aware of the inflationary situation and they also know that companies need labour. Add to this equation the 20% minimum wage increase, and we are sitting on a ticking wage bomb. Anecdotal evidence is pointing to double-digit wage increases even in those sectors, where minimum wages are not necessarily in play. In our view, gross average wages will increase by around 15% in 2022.

The impact of minimum wages and labour shortage on wage growth

We therefore continue to see a serious risk of extraordinary price increases both for products and services at the beginning of 2022. The November-December inflation might have already shown some earlier-than-expected repricing in some areas, but we wouldn’t rule out that more of the same will show up in the upcoming inflation figures. We see the 2022 average Consumer Price Index (CPI) at 5.7–5.8% YoY surrounded by further upside risks, partially stemming from the stronger wage-push inflation.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download snap