US yields are ignoring inflation - here’s another reason why

This gets a bit technical. If you want to skip that - and I don't blame you - then just use the simple 70bp rule. Take any Euro bond. Add 70bp to its yield. Then compare with an equivalent Dollar bond. Whichever one is higher is effectively the cheapest when FX adjusted. This goes for corporates, too. To understand why, read on…

US yields, even if low versus inflation, are elevated versus alternatives when FX hedged

Here we explain why some asset managers continue to favour US Treasuries, while liability managers do the opposite by funding in EUR (and JPY a.o.). Not just based on obvious rate differentials, but importantly, on all-in fully FX-adjusted ones.

Add 70bp to EUR rates to get comparable with USD.

Asset managers often use an annualised 3-month forward FX adjustment factor to help compare bonds in different currencies. It’s a vanilla adjustment that is easily understood, and makes for a quick and ready computation. Right now, that annualised FX adjustment is worth 70bp when comparing EUR to USD-denominated yields. Simply take the 70bp, add to the EUR-denominated bond yield, and compare that with the maturity matched USD-denominated yield. The value is in whichever one is higher (in reality, not that simple of course).

And by the way, the equivalent adjustment factor for JPY-denominated bonds is 30bp. Essentially, these adjustment factors reflect the benefit from buying USD 3-months forward using EUR (or JPY) FX rates that are stronger in the forward space. This FX pricing in the forwards reflects vanilla interest rate differentials (via textbook interest rate parity). As funding rates are lowest in the eurozone, the EUR appreciates most in the forwards. Hence the 70bp annualised attainable from buying USD forward using EUR.

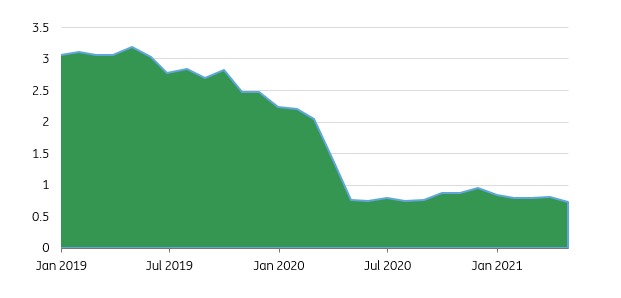

Add this to your EUR denominated bond to get a simple synthetic USD version (%)

That 70bp is in fact quite a tame FX adjustment factor relative to where it was in the years prior to the pandemic.

It was a 300bp adjustment in 2019, so things have changed.

In 2019, the adjustment factor was in the area of 300bp (see the chart above). The Federal Reserve had hiked towards 2.5%, and that elevation in the rates differential meant that the EUR was especially rich in the forwards. This implied 300bp adjustment factor absolutely dominated the bond yield differential. The spread between USD and EUR swap rates never went above 200bp, and even the spread from German Bunds to US Treasuries did not stray much above 250bp. The FX adjustment factor dominated these.

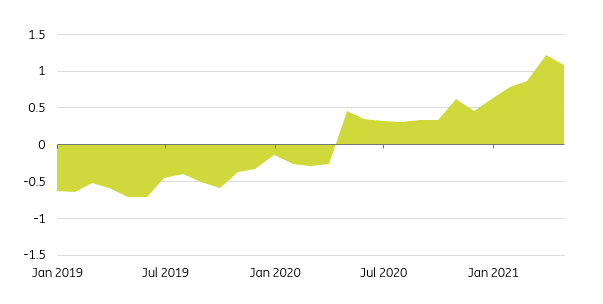

The implied arbitrage in 2019 then, was for holders of German Bunds to lend (bond repurchase) them for cash and employ that to buy USD 3-months forward. On an annualised basis that produced a 50bp pickup from US Treasuries into German Bunds synthetically transformed to USD. The implied pick-up in yield was even more in interest rate swaps, where an implied alpha of 100bp was attainable. That can be gleaned from the left half of the graph below (mostly 2019).

This is the difference between the US Treasury yield and the 10yr Bund yield when the latter is FX adjusted (%)

But as we progress towards today, a clear yield advantage in US Treasuries is in evidence (right hand side of the chart above). This has come from the Federal Reserve cutting rates as Covid first broke (reducing the FX hedge value to the synthetic Bund), and then the subsequent rise in Treasury yields added to the concession in Treasuries.

There is an all-in 100bp spread into Treasuries, FX adjusted.

We now find there is an implied 100bp spread from German Bunds to US Treasuries, where the German Bunds are FX adjusted as described above (so we compare synthetic USD to vanilla Treasuries). And in interest rate swaps, and the equivalent spread is 70bp.

In a static state, this is a rationale for global asset managers to like vanilla Treasuries. It also supports liability managers that borrow in EUR (or JPY). Simplistically, asset managers should be where FX adjusted yields are highest (maximise returns), while liability managers should be funding where FX adjusted rates are lowest (minimise funding costs).

There are issues with this simple methodology, but it does reflect well where the value is in a static state

The above is applicable in a static state, one where effectively FX rates and market rates don’t move. So, FX rates don't converge on the forwards. And we are implicitly agnostic as to maturity. These are eminently challengeable assumptions.

The idea in this static state is you get what you see. Nothing wrong with this, by the way. The advantage of this strategy is it is based off what we know, rather than what we forecast.

You can lock in what you see, or add dynamics.

When it comes to a non-static state, the biggest risk is that US rates head higher again. Despite the demand factors that support fixed income right now, there is an oomph to the US macro economy that is manifesting in higher inflation. That should result in higher market rates, and a wider spread into US Treasuries.

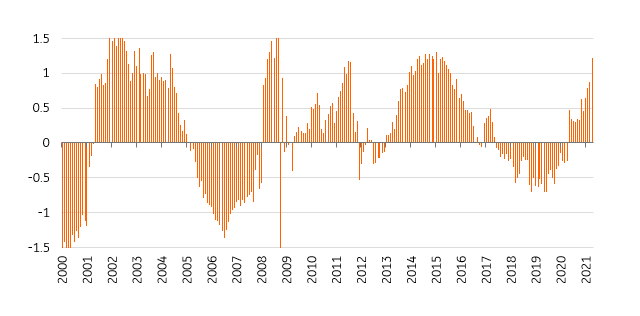

History shows that the fully FX adjusted spread between German Bunds and US Treasuries trades in a range between +1.5% and -1.5% (see the chart above). At 1% now, it’s nearing an extreme. That present opportunity. But based off our own forecasts, it is likely to peak out at closer to 1.5%. So the opportunity can improve, if rates do move higher.

The long term all-in spread to US Treasuries out of the German Bund when FX-adjusted

At the same time, that spread at 100bp today does in part explain why there is demand for US Treasuries when they optically present little real value when compared with core US inflation running at 3% (and headline heading for 5%).

We still think the US 10yr heads for 2%. But if we are wrong, it will reflect factors likes the ones described here. Ultimately, the US 10yr at 1.65% is a number that players can take or leave. The macro story suggests it should not be touched. But a glean of alternatives shows that on some measures it might be the best that’s attainable.

Some assets managers will use this as a rationale to accept buying into current US yield levels, perhaps adding more as market rates head higher. The same approach sees some liability managers choosing to receive the fixed rate on interest rate swaps, and again adding more should those fixed move higher.

These approaches are conservative means to approaching current quite tough-to-call market circumstances.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download opinion

Padhraic Garvey, CFA

Padhraic Garvey is the Regional Head of Research, Americas. He's based in New York. His brief spans both developed and emerging markets and he specialises in global rates and macro relative value. He worked for Cambridge Econometrics and ABN Amro before joining ING. He holds a Masters degree in Economics from University College Dublin and is a CFA charterholder.

Padhraic Garvey, CFA