Federal Reserve: 0% cash back

So much liqudity has been pumped into the system that chunks of it are being offered back to the Federal Reserve, at zero percent. Perverse, as players are effectively shuffling excess reserves back to where it originated from. Okay, there is a tad more to it than that. But what's all this about? Mostly it's policy perseverance. This Fed is still all in

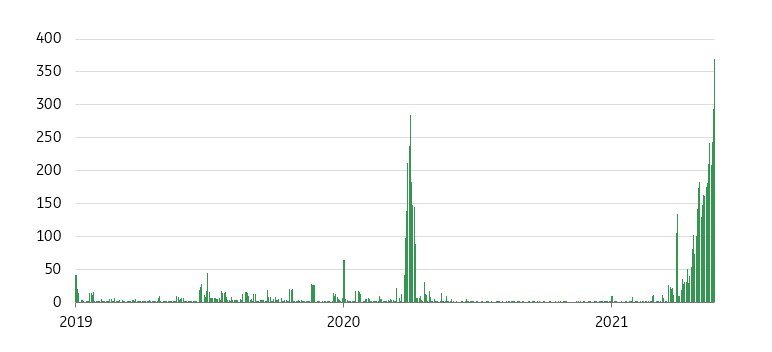

The US is awash with liquidity. So much so that almost USD370bn was placed at the Federal Reserve’s reverse repo window on Friday. That’s pretty much as high as it has ever been (or close to). The thing is, the liquidity is being placed here as there is nowhere else for it to go to. And it’s not really where you want to park cash, given that the rate paid to the cash lender is 0%. So what’s going on?

Size of cash volumes shipped back to the Federal Reserve through the reverse repo facility ($bn)

Fed bond buying adds liqudity

First, the Fed’s bond buying program is an ongoing factor. The Fed has bought more than USD2.5trn of bonds since the pandemic broke a little over a year ago, and this continues at a rate of USD120bn per month. This adds liquidity to the system. As the Fed buys bonds, those sellers receive the liquidity and likely buy other bonds, or other product. But either way the net effect is an additional of permanent liquidity into the system.

The perversion here is the Fed is getting a pile of this liquidity back through its reverse repo facility, where the Fed lends bonds and takes in liquidity. Effectively the Fed is adding liquidity through bond buying, but is also required to take chunks of it back in through its reverse repo window. It is not quite as simple as that, but in terms of cash in versus cash out they do act as an offset.

Deployment of cash raised by the Treasury also does

Second, the US Treasury has effectively financed a whopping deficit of some 20% of GDP ran in 2020 through bills issuance. While this on the one hand mops up liquidity, on the other it comes back into the system as it gets spent. And this is precisely what is happening now. The US Treasury had accumulated a balance at the Fed of some $1.7trn, which is now below USD 1trn, and as it continues to fall, it means an implied liquidity injection into the system.

Plus the Treasury is issuing less bills now, which means less mopping up is getting done. A bit circular this, but in the end liquidity is getting added.

While the reverse repo is at 0%, the rate on excess reserves is at 10bp - that's the real policy range

The important nuance here comes through bank reserves. Banks are required to have reserves for regulatory reasons, and they get a 10bp return on those. But banks can also post excess reserves at the Fed, on which they also get a 10bp return. If banks could not do this, they might not take in deposits. So this rate on excess reserves is important. In fact that 10bp on excess reserves in a sense frames where the Fed pitches the price of money. The Fed can also vary that rate as it sees fit.

The Fed’s zero rate on the reverse repo facility can also be viewed as a key rate, as it effectively sets a floor for rates. It’s where non-banks can post their excesses. As the price for this is fixed at zero, the quantity done at that price tells us where the dis-equilibrium bias really is. Right now, its one of excess liquidity.

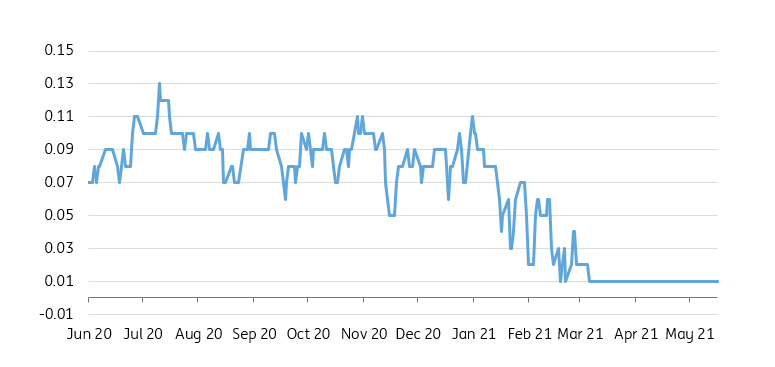

Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) has been flat-lining at just 1bp away from zero

Just above the implied reverse repo rate floor at zero sits the SOFR rate at 1bp. Its been there since mid-March, at bang on 1bp; has not budged. That too is a tad artificial, as it is in part being propped up by the Fed’s reverse repo zero rate facility at zero. The reality in this area of the curve is the market could actually clear with negative rates. In fact, US bills yields, which are determined by where supply meets demand, indeed print negative, right out to 6 months. This is in fact a negative rates environment.

The fed funds rate is another barometer of the future

Meanwhile, Fed funds policy rate sits at 6bp, between the reverse repo floor at zero and the 10bp rate on excess reserves. It has, at times, briefly dipped to 5bp. If it was to go below 5bp, there should be pressure for the Fed to coax it away from zero. The counter argument is the reverse repo facility at zero acts as a firm floor, and hence the funds rate would not dip negative. But the counter is the Fed may not want to take the risk that something breaks.

Given that the zero reverse repo rate is already artificial, the Fed could consider just raising it. Or push up the rate on excess reserves. Or both. But, the only way to really sort the dis-equilibrium would be to take liquidity out. Issuing bills is one way. The other could be for the Fed to stop buying bonds. Both of these are contentious. The US Treasury wants to get the weighting of bills down as proportion of overall debt, and the Fed wants to keep policy levers flipped to full-on easing mode.

The economy has made an impressive rebound since the re-opening phase really took hold. But it now needs to make the harder yards, to help get back to where we were for the most vulnerable US households, as policy is being set there as opposed to the traditional approach of targeting the median household. Given that, this weird world of fixed pricing in the face of liquidity avalanches is liable to remain with us as we progress over the next few months.

The lesson here is to continue to look at the volumes going into the Fed reverse repo facility as a measure of where the market bias is. And that is likely to show more of the same ahead. In turn this remarkable experiment of pumping liquidity in despite the elevation of inflation continued unabated.

And on the money markets, we continue with an inverted world of negative rates where the market is allowed to clear, versus artificially manufactured ultra-low but positive rates where the market can only clear by allowing bigger and likely ever bigger volumes to get shipped back to where they came from.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download opinion

Padhraic Garvey, CFA

Padhraic Garvey is the Regional Head of Research, Americas. He's based in New York. His brief spans both developed and emerging markets and he specialises in global rates and macro relative value. He worked for Cambridge Econometrics and ABN Amro before joining ING. He holds a Masters degree in Economics from University College Dublin and is a CFA charterholder.

Padhraic Garvey, CFA