Battle of the bad news stories – Brazil or Mexico?

It’s been a rocky couple of weeks for Mexico and Brazil. Here we look to contrast the two and identify both similarities and key differences. It’s the best of a bad lot, but we identify a greater comfort factor in Mexico over Brazil. Despite the pressures of late, Mexico still has considerable rate cut room once (or if) the dust settles. Brazil does not

Brazil and Mexico have had to contend with quite different circumstances. The difference matters

The first back story centres on the outcome of the presidential election in Mexico and associated concern with respect to judicial reform and broadly a more socialist agenda. It’s provided an excuse for the peso to revert in the direction of PPP fair value (in the 20/21 area). It’s been driven by a knee-jerk negative spin along the lines of what could go wrong for Mexico.

The second back story out of Brazil is a more classic one – the fiscal deficit. It was almost 9% for 2023, had been projected at 7% for 2024, and there is now upside to that as spending cuts are no longer being actively considered as a panacea. In addition, there is an implicit pressure being brought to bear on the central bank as a lower interest rate expense is being presented as a means to getting the deficit lower.

There are two quite different narratives here, and they come against very different central bank reaction functions. The fiscal woes coming out of Brazil are a clear negative credit event. In contrast, the narrative out of Mexico could end up being nasty, but then again it might not. The link between what’s happened and Mexico as a credit is more opaque.

Tight Banxico policy is still a good look relative to BCB

It’s also come against a backdrop where Banco de México (Banxico) has maintained a very tight policy stance. It might regret not having cut rates more to date, as its tight policy has not protected the peso completely. But it is a good look all the same. Our analysis shows that Banxico has capacity to cut by some 2.5% before it gets to a state of neutrality (detailed below). In contrast, Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) has engineered a significant rate-cutting process already, and has moved its policy rate some 50bp through its comfort level (in other words there is hike pressure).

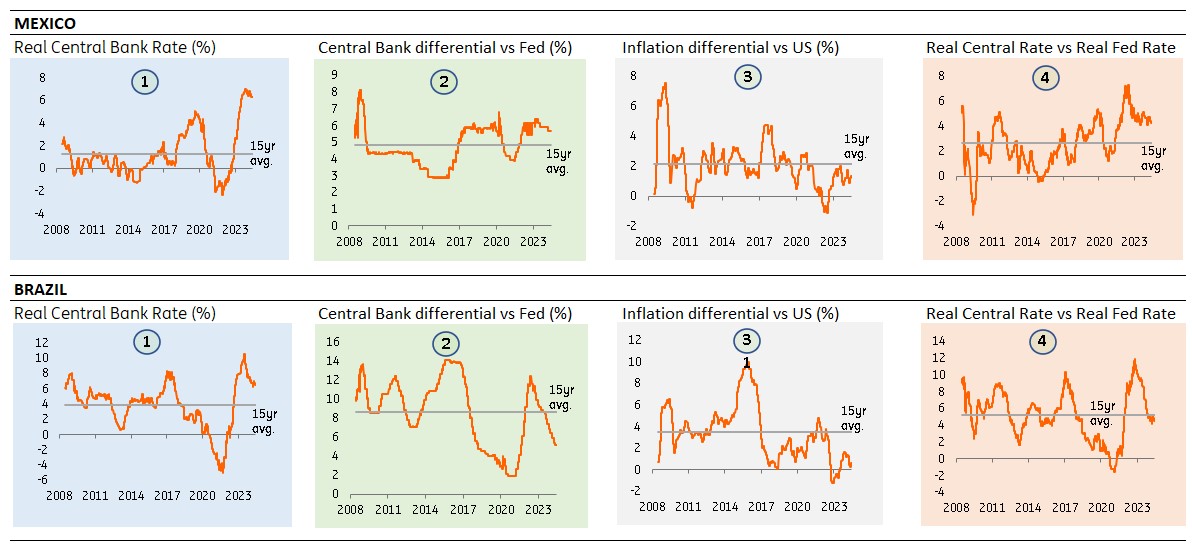

Let’s contrast the two a little more deeply. See the graphs below for a sequence of key indicators.

Contrasting Brazil and Mexico through key spreads

We show that Mexico still has big capacity to cut, eventually. Brazil does not. If it does there are risks

First, real policy rates for both Mexico and Brazil are comfortably positive versus the 15yr average. On that measure there is room for cuts, and especially from Mexico where the gap is especially wide.

Second, there is a contrast between policy rate differentials versus the Federal Reserve, where Brazil is well through the 15yr average, while Mexico sits comfortably above. Less room for cuts here from Brazil.

Third, inflation differentials versus the US look good versus history for both, mostly as US inflation remains more elevated than usual. Fourth, this helps to move the real policy rate differentials versus the US to more comfortable levels.

The specific numbers are below, where the current spreads are identified alongside their averages, and the delta is the difference between the two. We use an equally weighted average between 1, 2, and 4 to identify the potential for change in the central bank rate. For Mexico, that’s 2.4% (capacity to cut to c.8.5%). For Brazil it’s -0.4% (greater risk for a hike).

Quantifying the potential for changes in rates, alongside 2yr and 10yr market rates

There are risks to both, but we identify more comfort value in Mexico over Brazil

Note that a key determining factor here is the 15yr average, where we assert that this contains institutional information that summarises the policy and macro risk norms as built over the past 15 years. To change these norms, policy would need to improve (or dis-improve) in a structural manner. As it is, the norms we are working off pitch more elevated averages for Brazil, and hence the lessor capacity to secure rates that are lower than can be achieved in Mexico. This a priori assumption is open to criticism, but the events of the past week in fact don't help Brazil secure a better outcome.

The market rate differentials summarise where we are. The 2yr and 10yr Mexican spreads to SOFR are now very comfortable on spreads of 6.0% and 5.8% over SOFR in absolute terms. And at 1.2% and 1.0% above the 15yr average spreads. Value has been built here in the past week.

For Brazil, the absolute spreads are wider, at 7.1% and 8.2% for the 2yr and 10yr respectively. And there has also been some widening here in the wake of recent events. However, these spreads are below the 15yr historical averages, by some -1.7% in the 2yr and -0.8% in the 10yr.

Bringing this all together, it's the best of a bad lot, but we identify a greater comfort factor in Mexico over Brazil. Brazil is trading with higher rates, but Mexico has more capacity to perform relative to historical norms. What could go wrong here is Mexico goes off the rails and pressures its averages wider over time, and sure, that’s a risk we can't ignore. But Brazil faces in many ways a more direct hit to its credit credentials.

We are in the middle of an FX sell-off moment for both currencies (and the likes of the Colombian peso is doing something similar). That could indeed persist. Our FX strategists have identified 20/21 as a risk for the Mexican peso should things get nasty. From a rates perspective, if we get there, there would be quite elevated value in receivers.

Mexico still has considerable rate-cut capacity, and we believe will get back to the rate-cutting game in due course (especially as the Fed cuts). Brazil does not have the same room, and any future cuts there could pose more risk than benefit.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download opinion

Padhraic Garvey, CFA

Padhraic Garvey is the Regional Head of Research, Americas. He's based in New York. His brief spans both developed and emerging markets and he specialises in global rates and macro relative value. He worked for Cambridge Econometrics and ABN Amro before joining ING. He holds a Masters degree in Economics from University College Dublin and is a CFA charterholder.

Padhraic Garvey, CFA