World trade moves on

International trade was one of the success stories of 2020, contributing to the global recovery. But supply chain disruptions have created bottlenecks and the end of the Brexit transition period, and then the wait for a new WTO leader have not helped. There’s still a great deal of uncertainty, but there's also progress

Containers are coming

Container freight rates have been rising since mid-2020. A sign of capacity constraints in world trade, this reflected shortages of empty containers, from the disruption caused by container ship cancellations during the first wave of the pandemic and ongoing limits to port handling speeds due to health restrictions. This has caused increases in supply lead times, delaying the recovery of manufacturing production to a modest degree and adding to pipeline inflation pressures on the goods side.

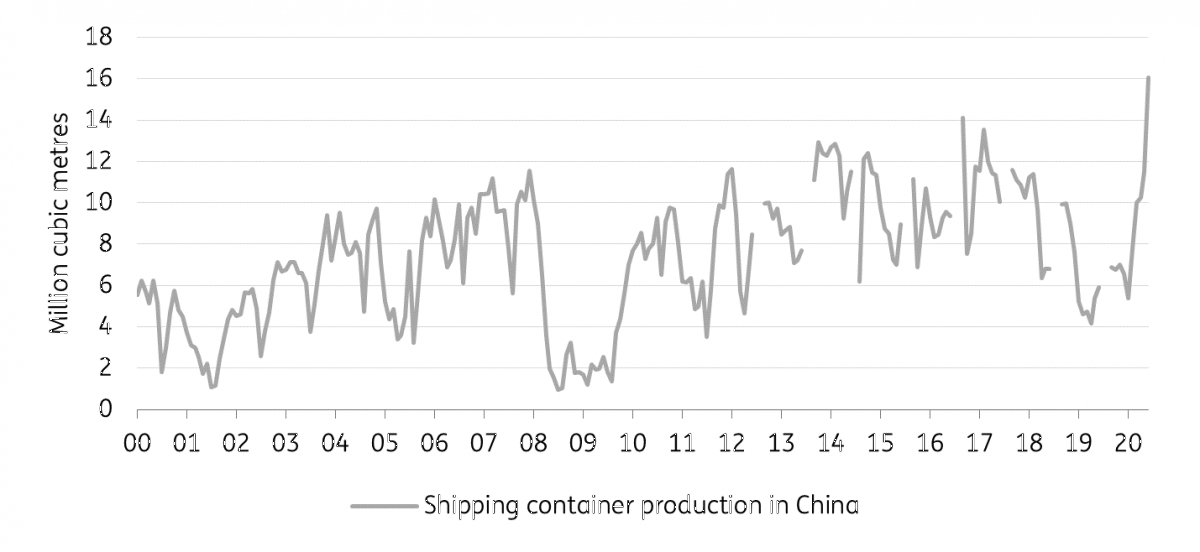

The enormous pressures on global shipping routes are not here to stay indeterminately. There is light at the end of the tunnel. But container supply is responding to the shortages, with empty containers being returned to China from US ports in record volumes, and major container manufacturers increasing production (Chart 1).

In time, this should help container supply meet demand again and reduce cost pressures.

Chart 1: New containers are being produced

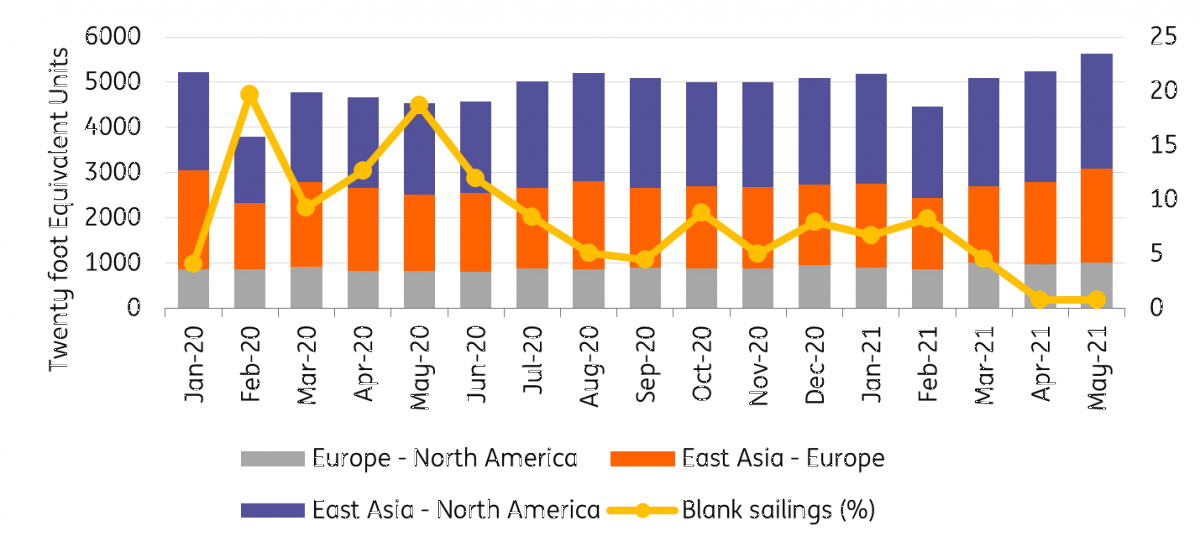

Container capacity is not the only thing set to increase. The amount of ships currently in use is also improving, adjusting to the surging global demand for goods.

Shipping routes are seeing capacity increasing and rebalancing across major trade lanes, with blank sailings back at very low rates, and Europe once again accounting for around half of sailings from East Asia (Chart 2).

Chart 2: More shipping capacity on major routes

Freight rates stabilised in February, but a reversal of the spike in rates will depend on how the shipping liners manage their capacity in the coming phase of the pandemic, and during the recovery. The tactic of cancelling sailings at short notice may be here to stay, in the near-term as a way of managing the uneven global demand while some countries remain in lockdown and others open up. Prices may stabilise for a time at higher rates, contributing to inflationary pressure for the rest of the year.

Ongoing limited capacity has meant shipping capacity has been slow to recover from supply chain disruptions early in the pandemic, both the greater supply of containers and normalisation of fleet capacity on the major trading lanes are necessary developments to help world trade to keep up when a global recovery gets underway.

Breathing space at the border

Trade volumes at the UK-EU border had surged in the last months of 2020 as firms front-loaded their exports to and from the UK, in anticipation of some disruption in early 2021.

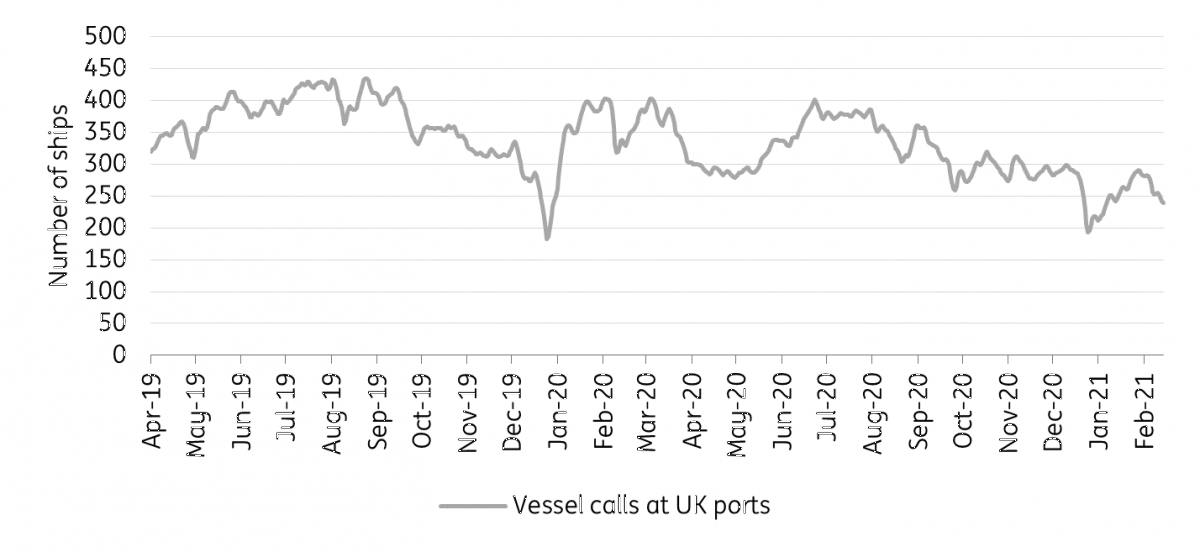

Now, lower rates of rejected cargo being transported in trucks indicate that new border paperwork is becoming a part of the routine. UK ports have also seen ship visits rising from their lows at the turn of the year, though they remain below their level during the first wave of the pandemic (Chart 3).

Chart 3: UK ports are handling more ships

Signs of normalisation and some increases in volumes suggest that some disruption from the new trade frictions will be temporary. This stands the UK and EU in good stead for the introduction of UK checks in April, which will progress to full border checks from both sides from July.

The improving picture for this particular bottleneck though hasn’t changed the likelihood of higher trade barriers leading to structurally less trade between the UK and EU over time.

WTO wait is over

The appointment of Director General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala ends the wait for the WTO to begin its part in tackling the higher tariffs and multiple disputes between countries that are the legacy of the trade war, and resume its work towards progressively lowering trade barriers, which have continued to increase during the pandemic. Trade barriers have proliferated in the form of state subsidies, which may not be easy to identify and remove in the aftermath of the current crisis.

The new Director-General cannot alone solve all the problems, but her appointment follows a welcome move from the US, that signals a new phase in participating with others in making trade policy. From her position, Okonio-Iweala has an opportunity to make the system benefit from the breakthroughs that have been made in smaller coalitions of WTO members – the commitment to lower tariffs between RCEP signatories, for example, and China’s agreements with the US and EU on market access for foreign investors.

Change at the top of the WTO is a first step towards putting global trade on a sounder footing than it has been in years, that could benefit the longer-term trend for global trade, but it all depends on the new Director-General successfully tackling the significant challenges on her plate.

Laying the groundwork

These signs of progress are not enough to secure a better outlook for trade in 2021, as so much depends on the global economic recovery.

However, the easing of container capacity constraints, in particular, suggests that, given a recovery in demand, world trade could continue to contribute to the global economic recovery. There are some positive signs that new processes at the UK-EU border can be absorbed without too much disruption. And there is positive momentum in trade policy, where new management and dialogue are prerequisites for finding solutions to some of world trade’s most difficult issues.

"THINK Outside" is a collection of specially commissioned content from third-party sources, such as economic think-tanks and academic institutions, that ING deems reliable and from non-research departments within ING. ING Bank N.V. ("ING") uses these sources to expand the range of opinions you can find on the THINK website. Some of these sources are not the property of or managed by ING, and therefore ING cannot always guarantee the correctness, completeness, actuality and quality of such sources, nor the availability at any given time of the data and information provided, and ING cannot accept any liability in this respect, insofar as this is permissible pursuant to the applicable laws and regulations.

This publication does not necessarily reflect the ING house view. This publication has been prepared solely for information purposes without regard to any particular user's investment objectives, financial situation, or means. The information in the publication is not an investment recommendation and it is not investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Reasonable care has been taken to ensure that this publication is not untrue or misleading when published, but ING does not represent that it is accurate or complete. ING does not accept any liability for any direct, indirect or consequential loss arising from any use of this publication. Unless otherwise stated, any views, forecasts, or estimates are solely those of the author(s), as of the date of the publication and are subject to change without notice.

The distribution of this publication may be restricted by law or regulation in different jurisdictions and persons into whose possession this publication comes should inform themselves about, and observe, such restrictions.

Copyright and database rights protection exists in this report and it may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any person for any purpose without the prior express consent of ING. All rights are reserved.

ING Bank N.V. is authorised by the Dutch Central Bank and supervised by the European Central Bank (ECB), the Dutch Central Bank (DNB) and the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). ING Bank N.V. is incorporated in the Netherlands (Trade Register no. 33031431 Amsterdam).