Why the UK-US trade deal won’t herald a wider tariff climbdown

For Britain, the UK-US deal secures lower tariffs without compromising forthcoming UK-EU talks. And for the US, it signals to investors that the adminstraion is prepared to be flexible on tariffs. But we're sceptical that the deal will translate into a much wider de-escalation in US tariff policy

The UK-US deal offers Britain much needed relief from sectoral tariffs

President Trump has revealed that the UK is the first country to receive carve-outs from some – though crucially not all – of the tariffs he has introduced over recent months.

At face value, the UK seems to have done quite well – at least relative to the reports circulating in recent days. According to the UK’s press release, tariffs on British steel and aluminium go to zero, with no talk of quotas. And although UK car exports are subject to a quota of 100,000 vehicles, this essentially means that UK car exports, or the vast majority of what was exported in 2024, will see 10% tariffs rather than 27.5% (2.5%, plus Trump’s additional 25% rate). Cars represent roughly 10% of UK exports to the US.

As far as we can see, the concessions offered by the UK aren’t considerable. Britain reportedly won’t make changes to its Digital Services Tax, which applies to the big tech firms (though it is a relatively small revenue-raiser). And importantly, the UK has said it isn’t changing its food standards. Remember it’s that – not tariffs – which is the more significant barrier to entry for certain US agricultural products, beef and chicken being the most notorious.

Crucially, that means the US deal won’t jeopardise British attempts to build closer trade ties with the European Union. The UK hopes to conclude a veterinary deal with the EU, which would remove the most cumbersome checks at the border and would see Britain formally aligning on food standards. This should be relatively easy, on paper, given the UK hasn’t meaningfully diverged since Brexit – on food, or on goods more generally.

Securing closer access is a key priority for the UK government, as it tries to rebuild the public finances. Both sides meet for a summit on 19 May, though this is centred more on defence than trade.

UK goods exports to the US (2023, GBP bn)

The deal shows investors that the US administration can be flexible on tariffs

That all said, details about the UK-US deal are scarce. And it is a reminder that for all the hype, this represents a relatively narrowly-focussed deal. The impact on the UK economy of these changes will be fairly negligible, given the direct hit from Trump’s tariffs wasn’t huge in the first place.

For the US though, the deal enables the President to offer the sense of flexibility that financial markets are craving. The reaction – higher equity prices, a stronger dollar, higher Treasury yields – shows that it has had the desired effect.

It may also indirectly help the US add pressure on China. Comments from Commerce Secretary Lutnick in the Oval office hinted that the administration, as part of the deal, will put pressure on the UK to go further on anti-dumping measures against Chinese metals. We know, separately, that raising barriers to Chinese-made products entering Canada and Mexico has been a factor in recent trade talks there. Though there’s little detail on how this will work in the UK’s case, it will almost certainly form a key US ask in negotiations with other countries.

Will this herald a wider climbdown on tariffs? We're not convinced

Still, we’re sceptical that the UK’s deal will herald a much broader climbdown from the US administration. A UK deal was relatively low-hanging fruit, given the US has a trade surplus in goods with Britain (even if, ironically, UK trade statistics say the opposite). Lutnick referred to the trade relationship between both countries as ‘balanced’.

If you look at cars, most of what the UK exports across the Atlantic are luxury models, which represent less of a threat to the big US domestic producers. Other countries, whose manufacturers are more direct competitors, may find it harder to negotiate carve-outs from Trump’s auto tariffs – or where deals are done, the import quotas may be less generous than the one agreed with the UK.

Remember too that even the UK hasn’t succeeded in negotiating away the 10% baseline tariff. Our base case is that this remains in place, for all countries, throughout President Trump’s term. His comments in the Oval Office today, where said 10% was a “low number”, appeared to reinforce that.

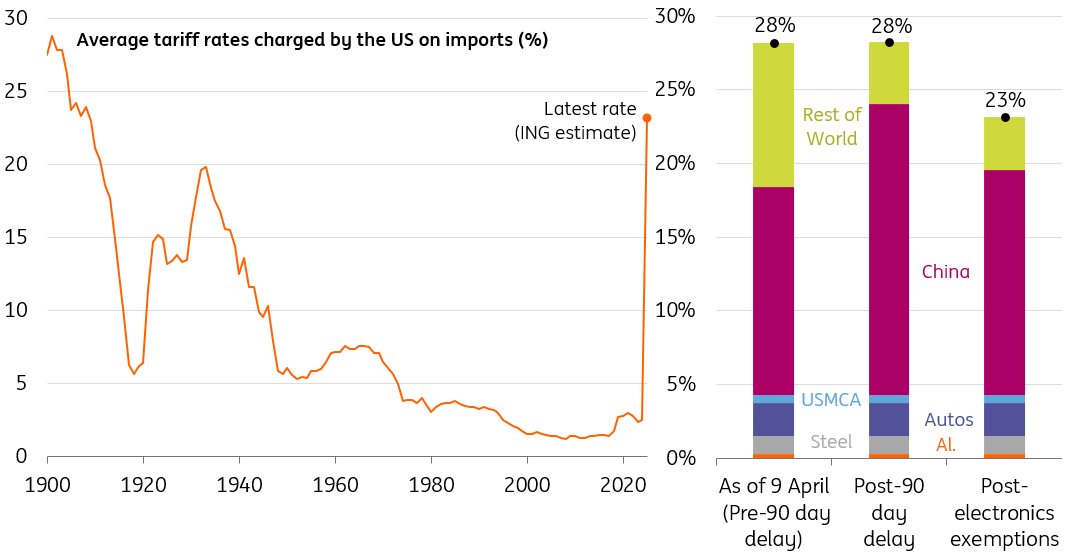

The average tariff rate on US imports has surged from 2% to 23%

Stepping back, the average tariff now charged by the US on its global imports is now around 23%, up from 2% before President Trump’s inauguration. We estimate that Trump’s auto, steel and aluminium tariffs across all countries make up less than four percentage-points of that. And were the President to introduce tariffs on pharmaceuticals, semi-conductions, timber and copper, as he has previously threatened, and as the ongoing Section 232 investigations suggest, that average would rise by a further two percentage-points.

Conversely, China’s 145% tariffs make up more than 15 percentage points of that average tariff rate, even after the recent electronics exemptions. In other words, a de-escalation with China is realistically the only thing that can meaningfully move the dial on the tariff hit. Our China economist discusses the prospect of US-China talks in our latest ING Monthly.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article