Don’t bet on a ‘no deal’ Brexit after a UK election

A UK election looks almost inevitable, and should that yield a Conservative majority, the sense is that a ‘no deal’ Brexit would become more likely. However, there would still be incentives for the government to secure a deal – not least because exiting the EU without one could prove risky if there's another future snap general election

The risk of 'no deal' has been postponed but not eliminated

A ‘no deal’ Brexit on 31 October now looks pretty unlikely.

Admittedly so do the chances of a deal being agreed with the EU and approved by Parliament over the coming days. Negotiations are on the verge of breaking down amid a lack of agreement on customs alignment on the island of Ireland.

Come the 19 October, the absence of a deal would mean the government will be obliged to seek an Article 50 extension. If it doesn’t, the issue is likely to quickly find its way into the courts - but one way or another a further delay to the Brexit process is probable.

The ‘no deal’ risk will not disappear indefinitely

This will almost certainly open the door to a late-2019 general election, most likely brought about by a vote of no-confidence in the government.

For the time being, sterling has taken comfort from this reduced likelihood of 'no deal' Brexit. Our FX team reckons there is now virtually no risk premium in the currency, compared to around 5.5% two months ago.

But even if the next few weeks play out as we – and investors – assume, the ‘no deal’ risk will not disappear indefinitely.

Conservatives are leading in the polls, although a 2019 election would be unpredictable

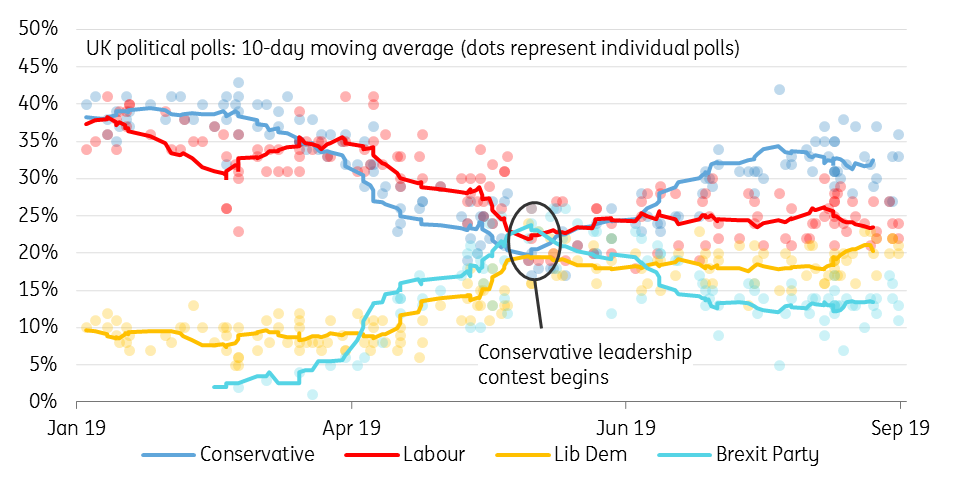

The Conservatives are riding high in the polls – the party is currently surveying around 30-35%. At the same time, both Labour and the Lib Dems are averaging in the low-to-mid 20s. In the UK’s first-past-the-post electoral system, these numbers theoretically could translate into a comfortable majority for the Conservatives.

The reality is much more unpredictable - a volatile political backdrop could easily yield a very different election result to the one currently painted by the polls.

But if the surveys are right and the Conservatives do indeed command a majority after an election, the feeling is that the risk of the UK leaving the EU without an agreement would rise.

However, we don’t think ‘no deal’ would become inevitable. Leaving with a deal would arguably still be a better longer-term tactic for the Conservatives.

The latest UK political polls

The EU is no more likely to sign up to UK proposals after an election than it is now

The first question this poses is: how realistic is a deal after an election?

Well despite running a hardline Brexit campaign, we assume a newly re-elected Conservative government would return to the negotiating table. In the first instance, the government may simply re-table its current proposals.

Brussels is unlikely to be any more sympathetic to the current British proposals after an election than it is now

According to a lengthy briefing from a Number 10 source in The Spectator, the UK believes the EU may be more open to negotiate after an election.

The article quotes the government figure as saying “Varadkar [Irish Taoiseach] thinks that either there will be a referendum or we win a majority [in an election] but we will just put this offer back on the table so he thinks he can’t lose by refusing to compromise now”.

A ‘no deal’ Brexit would undoubtedly be negative for the Irish economy, and there’s a line of thinking in Westminster that Ireland may ultimately move towards the UK’s proposals to avoid the potential damage.

However this arguably misrepresents the EU position – both in Dublin and other EU capitals.

There are several reasons why Ireland is unlikely to ditch the backstop - this insightful piece from The UK in a Changing Europe looks at some of these arguments in much more detail. The most obvious concerns relate to the long-term peace process, but three tactical considerations also stand out:

- If Dublin signs up to a deal that effectively guarantees a hard border, it could be viewed very unfavourably by the Irish electorate

- The Irish government's leverage could be gradually diminished in the second phase of trade talks, as a myriad of other economic and strategic interests of individual EU members come to the fore

- The UK’s negotiating position could be weakened by ‘no deal’, potentially making it more likely the British converge back towards the current backstop in the longer term.

For the EU more broadly, concerns surrounding the future solidity of the single market, as well as a reluctance to grant the UK an exception to the EU's customs code, are unlikely to change.

Two reasons why 'no deal' would be tricky for the Conservatives

In other words, the EU is unlikely to be any more willing to sign up to the current UK proposals after an election, meaning the situation will probably move back to square one. Either the UK government pivots back to something that more closely resembles existing backstop solutions (e.g. where Northern Ireland alone stays in a customs union), or the alternative may well be ‘no deal’.

On the latter, it is worth remembering that the ability of Parliament to block a ‘no deal’ may well be diminished if the Conservatives secure a majority in an election. By definition, the government will no longer need to worry about the 21 MPs that were ousted from the Conservative party for voting in favour of the Benn bill a few weeks ago.

But there are two key reasons why ‘no deal’ could cause longer-term problems for the Conservatives.

Firstly, ‘no deal’ would do anything but “get Brexit done”. Trading with the EU on WTO terms is not sustainable and ultimately a trade deal will need to be agreed. But this will take time – potentially several years. Looking at process alone, a new negotiating mandate will need to be agreed by the EU. Depending on the scope of the final deal, it may require unanimous approval in the European Council, and potentially Parliamentary consent from individual member states.

If nothing else, this lengthy process will take up a lot of the UK's time and resources, reducing its ability to focus on other domestic priorities. That could feasibly create issues for the party at the next election.

Secondly - and speaking of elections - it would be unwise to assume that a late-2019 vote will be the last. An election in November or December would be the second snap poll in just two-and-a-half years, and given the economic risks posed by a ‘no deal’ Brexit, it’s conceivable that a third could come along earlier still.

Given the volatility and highly diminished party political allegiance among voters these days, another election amid the fall-out of ‘no deal’ would be incredibly risky for the Conservatives.

Summary

The upshot is that it would be unwise to write off the risk of 'no deal', on the basis that it is unlikely to happen on 31 October.

That said, there are reasons to think a 'no deal' Brexit could still be avoided after a general election, even if the Conservatives were to gain a majority. A lot will depend on the party's short-term wariness about losing ground to the Brexit Party, relative to the longer-term risks posed by leaving the EU without a deal and what that may mean at a future ballot box.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more