When ‘nudging’ becomes ‘sludging’

Are the choices we make ours alone or have we subconsciously been 'nudged' into them by clever marketing? And is this a good thing for society? We reflect on the concept of 'nudging' 10 years after Richard Thaler brought the theory to prominence

What's a 'nudge'?

This year, we celebrate the 10th birthday of ‘Nudge’, the best-selling book by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein. In Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness (2008), the American professors introduced the powerful idea of nudging. A nudge is a subtle change in the ‘choice architecture’ (the way choices are presented to consumers) to encourage shifts in behaviour. Simply put, it can help people and societies make wiser choices (or avoid mistakes) without restricting their freedom.

To understand how nudges can help us make better decisions, it’s important to consider why we often make bad choices in the first place.

Tricks of the Mind

The ability to choose seems to us to be a very powerful tool. However, we humans have developed various psychological quirks and mental shortcuts (so-called heuristics and cognitive biases) to make our decision-making time on earth more bearable. Sometimes, these shortcuts lead to good decisions more quickly, but frequently they trick our minds to make unconscious mistakes.

Remember Barack Obama and his suits? He only wore grey or blue suits to limit his choices about what to wear. Limiting choice formed a smart mental shortcut that let him spend his time on other – far more relevant – decisions, he said.

But many of us are also subject to the status quo bias. This is based on another common psychological quirk: we like sticking to the default choices because inertia makes us resistant to change. Just think of your health insurance or your mobile subscription: how often do you switch deals? Because of our tendency to leave things as they are, the use of pre-selected options is then one of the most subtle but powerful nudges that companies may use to influence people’s decisions.

And here’s one more popular nudge involving a third option. Say you sell shirts and have two products, a cheap one (€30) and an expensive one (€70). Just adding a third ultra-expensive product (€250) next to the other two will make more people buy the shirt that costs €70, because now they think €70 is a bargain. By carefully architecting people’s choices, you can ‘nudge’ them to pick the most beneficial option for themselves. Or, you can tempt them to follow someone else’s interest.

Are consumers aware of such subtle ‘choice architecture’ design changes? And should we welcome commercial nudging? Only if it benefits the individual or if it promotes the public good, Thaler and Sunstein recommend. That is called nudging for good.

From nudging to sludging

If you think about it, it all comes down to ethics. So which ethical principles should ‘nudges for good’ be built upon? Thaler and Sunstein propose the following principles:

- The nudge should be transparent and never misleading.

- The original set of choices should remain available.

- It should be easy to opt out of the nudge (for example, in a single click).

- The behaviour being encouraged should improve the welfare of those being nudged.

If a nudge is built on all of the above principles, we’re dealing with a ‘nudge for good’. If any of the four principles is violated, particularly the last one, Thaler himself calls it a ‘sludge’ – ‘a nudge for bad’. Sludging takes advantage of cognitive biases and choice architecture. People are sludged towards behaviours that are not in their best interests but may benefit a company or government instead.

According to Sunstein, sludges usually lead people to waste time and/or money, resulting in future regrets. Think of an unhelpful pre-selected option that persuades people to purchase excessive insurance or make foolish investments. This is exactly the stuff that complex subprime mortgages were made of. Evidence shows that these were marketed to the less-educated and less-wealthy customers who would never be able to pay their mortgage if a real-estate crisis hit.

Nudging for good, better, best

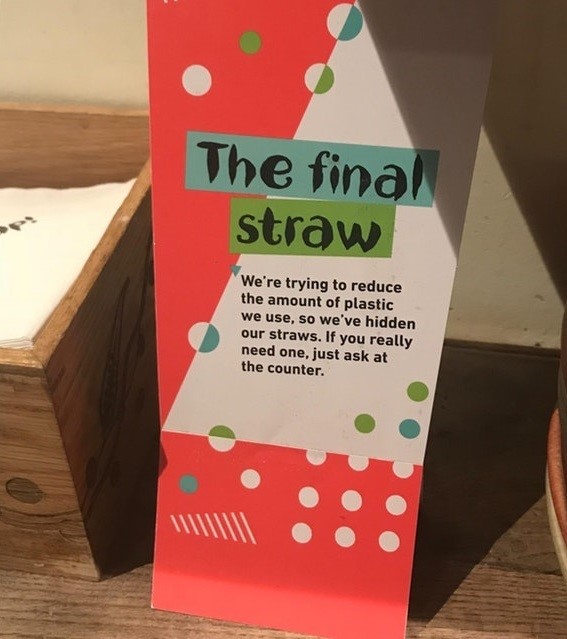

Nudges for good could relieve concerns about the ethics of (covert) manipulation of behaviour. One simple and powerful example of a good nudge is the 'Final Straw’ campaign, which boosts awareness about the impact of consumer choice.

The key here is transparency. The British House of Lords (2011) suggested two criteria to determine whether a nudging intervention is ethically acceptable. ‘Choice architects’ should either (1) tell people about the nudge directly or (2) ensure that perceptive consumers can discern the implementation of a nudge. Indeed, disclosing the intention behind a nudge encourages people to evaluate more sceptically the potential effect of choice architecture, and to actively identify whether the steered option is actually in their interest.

But does nudging still work when people are aware they’re being nudged? Recent studies conducted in Germany, the Netherlands and the US have confirmed that nudges can indeed be made transparent without reducing their effectiveness. This has been shown to work in various contexts (from saving money or energy to eating healthy food) and in various forms (e.g. default options, opt-ins/outs, or reminders). Research also shows that disclosing information on the potential behavioural influence and/or purpose of the nudge does not trigger psychological reluctance.

The lesson from these studies is that, overall, consumers appreciate transparency. They are likely to favour a certain choice architecture if they believe that it has a legitimate goal and if it fits with their interest and values. This support evaporates when people suspect a sludge. Upfront disclosure improves their perceptions of the fairness and ethicality of the nudge, and their willingness to cooperate again in the future.

Cleaning up the sludge

It is clear that companies should not – and don’t need to sludge their (potential) customers. But the way to a sludge-free world also depends on how we behave as consumers: we must resist the sludges that are still in effect. The more often we turn down questionable offers, the less incentive we give companies to turn to such schemes. If, instead, we reward companies that act in our best interests, nudges for good will survive and flourish, and the options available to us will improve.

And how about policymakers and other consumer advocates? Should they not be encouraging consumers to stop and pause when facing a nudge… or a sludge? Yes. This would probably diminish the biasing effect of nudging, enabling consumers to make choices they themselves deem to be in their best interests. As personally pleaded by Thaler in a recent article: “Less sludge will make the world a better place.”

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Tags

ConsumerDownload

Download article

12 September 2018

In case you missed it: The surprising and predictable This bundle contains 9 Articles