What to expect at the January Fed meeting

The Federal Reserve should leave interest rates unchanged, but we anticipate an immediate end to quantitative easing (QE) asset purchases

Building to a March hike

On the face of it, the 26 January 2022 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting should be a non-event. Speaking at his Senate confirmation hearing on 11 January, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell set out a clear timetable for events: “As we move through this year … if things develop as expected, we’ll be normalising policy, meaning we’re going to end our asset purchases in March, meaning we’ll be raising rates over the course of the year… At some point perhaps later this year we will start to allow the balance sheet to run off, and that’s just the road to normalising policy.”

With the economy regaining all of its lost output, inflation running at its highest rate since 1982 and the unemployment rate dropping below 4%, there is plenty to justify “policy normalisation”. Financial markets are now fully pricing a March rate hike with a further three moves expected during the course of 2022.

An even earlier end to QE?

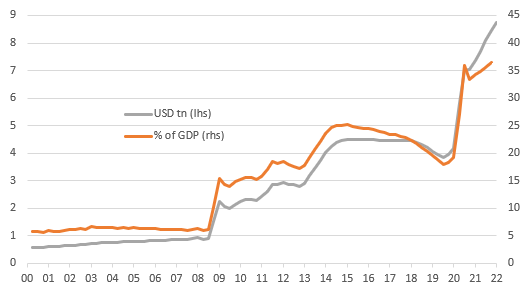

Given this backdrop there is the obvious question, why is the Fed saying it will keep buying Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS) through to mid-March? After all, Powell acknowledged at the same hearing that “we’re mindful the balance sheet is $9tr. It’s far above where it needs to be”.

Price pressures continue to broaden and deepen with the latest increase in energy prices heightening the prospect of an extended run of above-target inflation. At the same time, the competition for labour is resulting in record job quits and it means that companies are not only having to pay more to recruit new workers, but also pay more to retain the ones they currently have.

Consequently, employment costs rose sharply in the third quarter of 2021 and next Friday’s (28 January) 4Q Employment Cost Index could show a similarly steep rise, increasing the prospect that inflation pressures remain elevated for longer than the Fed had envisaged.

We therefore see no reason for the Fed to continue purchasing assets and expect them to announce an immediate conclusion to their QE asset purchase program. This earlier corrective action on the balance sheet would also help reduce talk of a potential 50bp March rate hike, while opening up the possibility of an earlier start to a shrinking of the balance sheet.

The Federal Reserve's balance sheet in US dollars and measured as a proportion of US GDP

50bp calls look implausible

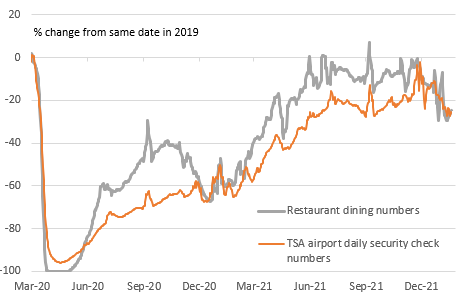

Talk of a possible 50bp move seems far-fetched to us. High-frequency data suggests the break-through of the Omicron variant has heightened Covid wariness and people movement is significantly down on early December levels. Restaurant dining and air passenger figures are 30% lower than what would ordinarily be expected at this time of year. Worker absences due to Covid quarantining also appear to be impacting economic activity with the potential for a decline in January non-farm payrolls signalled by some surveys, while we expect 1Q GDP to come in close to just 1% annualised.

The Fed would be highly unlikely to move by 50bp in this situation, but a 25bp could be justified on the basis that Omicron intensifies production bottlenecks and inflation pressures. With Covid case numbers also now falling in the US we are hopeful that we will see a rebound in consumer and business activity in February and March, particularly the rising wage narrative and the strong platform that a $30tr increase in household wealth through the pandemic provides.

Covid caution is hurting consumer demand for services

Balance sheet to do the heavy lifting

As we recently wrote in our outlook for the Fed’s balance sheet, further interest rate increases are coming – most likely at a pace of one per quarter. Some analysts are more forceful, proposing five or maybe even six, but we think earlier, more aggressive action on balance sheet reduction can do a lot of the heavy lifting in terms of “normalising” policy.

Given the balance sheet has more than doubled in size during the pandemic, there is a strong case for the Fed shrinking the balance sheet by at least double the initial rate seen in 2015-17 of $6bn Treasuries and $4bn agency MBS per month. We would suggest that within six months of the March rate hike we would see the Fed allowing $10bn and $6bn per month initially being allowed to roll off before swiftly going up to $50bn and $40bn per month. Officials note that the current weighted average maturity of the Fed’s holdings are shorter than five years ago, so this structural change means the balance sheet can certainly shrink more quickly than it did last time.

In terms of how far they could go, Christopher Waller, member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, suggested in December that he would like to see the balance sheet brought down to around 20% of GDP from the current 36%. Assuming average nominal GDP growth of 5% over the next three years, this would imply a balance sheet of roughly $5.4tr, which would mean the Fed offloading $3.4tr of assets.

This can certainly contribute to the yield curve remaining steeper with the long end moving higher relative to if the Fed focused on raising the Fed funds target rate. It would also mean that the terminal rate for Fed funds may be closer to 2% rather than the 2.5% the Fed is currently projecting.

New faces for the Fed

The usual annual rotation in FOMC voters sees Esther George, James Bullard, Loretta Mester and the new Boston Fed chief (to be announced – Kenneth Montgomery in the interim) replace Mary Daly, Raphael Bostic, Thomas Barkin and Charles Evans. On the face of it, this is a hawkish shift with Bullard one of the most vocal hawks while George and Mester haven’t been shy in making the case for normalising policy in the face of rising price pressures. Bostic was a slight hawk and Daly had started to sound more inclined to normalise policy faster, but Evans was on the more dovish end and Barkin seemed to be somewhere in the middle.

President Joe Biden does have vacancies within the Fed’s Board of Governors and he is seeking new members that fully buy into the narrative of a more “inclusive” Fed that would put emphasis on the need for a broader range of people feeling the benefits of economic growth. This means we may see candidates that are willing to tolerate higher inflation in the near term to achieve that aim, but it is hard to imagine anyone being approved that would argue against tighter monetary policy. Given the regional Fed member changes and the likely Board of Governor changes, the balance of the spectrum of the views within the Fed may stay relatively unchanged versus last year.

Here's some questions that could be posted to Chair Powell, on liquidity, collateral and real rates

It will be interesting at the post-meeting press conference to see how technical the conversation gets, specifically on the implications from balance sheet reduction. From the money markets perspective, a Fed unwind of purchases is overdue. There is a dearth of collateral versus an excess of liquidity in the system that has come about in a large part due to balance sheet expansion. The US$1.6tr going back to the Fed on the overnight reverse repo facility on a daily basis is an implication of this; liquidity that is happy to take the 5bp (annualised) on offer from the Fed, as that’s better than what’s attainable on an all-in market repo. Balance sheet reduction will help raise the collateral / liquidity ratio, allowing repo to ease up to more sensible levels.

Fed officials have been busy perfecting a standing repo facility. This is the opposite to the reverse repo facility, in the sense that it would allow participants to get access to liquidity (in exchange for collateral). This has little use right now, as the market is long liquidity. But it comes in handy when the Fed is reducing its balance sheet, which is precisely what the Fed is preparing to do. We think there is ample room to reduce the balance sheet before liquidity really tightens (think of the US$1.6tr going back to the Fed for starters as a type of a liquidity buffer that could, in crude terms, be taken out). However, should things creak earlier than expected, the standing facility helps to ensure that liquidity is continuously available to the market. The Fed should be quizzed on this, just to get their thoughts on how this could or should work.

There may also be some commentary on what’s happened to longer tenor market rates in the past few weeks. The Fed is likely to be pleased that inflation expectations have eased; a sign that their hawkish ambitions are already reaping some benefit. The big rise in market rates so far this year has been in real rates – up a substantial 50bp in the 10yr since 1 January. Yet there is room for much more, with the 10yr real rate still deep negative in the -60bp area. Some Q&A on this would be welcome. Our view is that this represents room to the upside, and that a zero 10yr real rate should be a minimum objective if we are really back to normal. It would be interesting to get the Fed’s view on this.

FX: Speed of the rate adjustment key for currencies

The dollar has started the year on the backfoot – generally on the view that the Fed cycle is (nearly) fully priced and that better opportunities are seen outside of tech stocks and US markets in general. But as discussed above, there still seems plenty of room for US real rates to move higher and we would argue that the current pricing of the Fed terminal rate at 1.70% is still conservative.

Presumably, if the Fed decides to call time on QE buying a little earlier than expected, US bond yields will rise and investors may be tempted to think that the Fed's balance sheet will do the heavy lifting in terms of normalising policy. This could be seen as a mild dollar negative in that it has been the Fed tightening story driving the dollar higher since last summer. Yet higher US real rates are typically associated with broad gains in the dollar and we would see any dollar dips post Wednesday's FOMC meeting as short-lived.

Perhaps the key question is how quickly US real rates adjust? Too quick and risk assets such as equities (tech stocks again) and credit markets could come under pressure. A lower Australian dollar / Japanese yen is typically used to hedge such equity weakness. But typically the Fed tends to manage this type of communication well and our base case would be an orderly adjustment in markets such that the dollar can start pushing higher again versus the euro and yen through February and March. Despite having a high beta to risk, we would continue to expect the energy-exporting currencies of the Canadian dollar and Norwegian krone to out-perform on the crosses.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article