US debt ceiling torture heightens recession risk

Debt ceiling deals always happen, eventually. But this time it will be especially challenging given a split Congress and politicians willing to go to any extreme to score political points. The best outcome would still see volatile markets and insecurity for government workers, while worst case we see a debt default and the prospect of a deeper recession

The debt ceiling and the risk of default

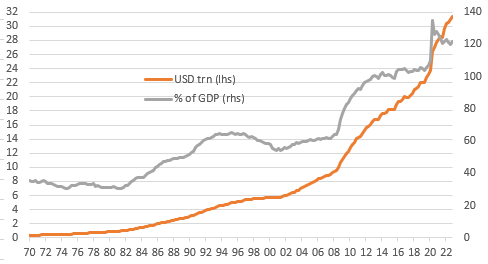

In most countries, when government spending plans are voted on and approved, said government can simply borrow what it needs to fund the programmes. In the US, it isn’t so straightforward. Introduced in 1917, the debt ceiling is a cap on the total level of government borrowing, so periodically a separate vote is required to either suspend the limit or lift the cap on borrowing. Failure to do so means the US government can’t borrow any more money, leading to the very real risk that it cannot fund its obligations, including paying its workers and the interest on its outstanding debts. That is the situation we find ourselves in today with government borrowing right at the $31.381tn limit.

US government debt held by the public

Over the past 106 years, the ceiling has been raised well over 100 times, mostly without major incident. However, recent years have seen more fractious politics on Capitol Hill and it has taken longer to come to an agreement. This year looks to be even worse with real concern that intransigence on both sides leads to government departments shutting down, workers being furloughed without pay, debt downgrades (as occurred in 2011) and an intentional default for the first time in America’s history.

Extraordinary measures give us some breathing room

While the debt ceiling has now been hit, it doesn’t mean that default is imminent. Workers will still be paid for now and interest and maturing debt will be paid in full. That is because Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has enacted what are called “extraordinary measures” – shuffling money around to buy some time for politicians to agree to an increase in the debt ceiling. This will likely only carry us through to July though - some have suggested we have until August or September, but we are doubtful given April tax receipts may not be as good as last year due to equity market declines weakening capital gain tax revenues. When these extraordinary measures are exhausted the debt ceiling must be raised or suspended, otherwise the government won’t have the money to pay its bills.

Congressional challenges

What makes this year more challenging is that we now have a split Congress with the House controlled by the Republicans and the Senate controlled by the Democrats. 60 Senate votes are needed to raise the debt limit, but the Democrats only have 51 seats. That means either nine Republicans need to side with the Democrats, or as what happened last year, Republicans eventually acquiesce and allow it to pass via a simple majority vote.

The bigger problem is the House of Representatives. Republican Kevin McCarthy made numerous concessions to rebels within his party to secure the position of Speaker in the House (at the 15th attempt). This includes agreeing to procedural rules that only one lawmaker is required to initiate the removal of his powers.

The upshot is that he is effectively bound to the extreme fiscal hawks who will demand big spending cuts as a condition to raise the debt ceiling. The Democrats and several moderate Republicans will undoubtedly oppose and we will get gridlock and the clear threat that the debt ceiling is not raised.

The solution would be for just a handful of moderate Republicans to vote with the Democrats (only a simple majority is required) to raise the debt ceiling against the protest of their party leadership. But again this isn’t as easy as it sounds because of the so-called Hastert Rule – an informal agreement that means a majority of Republicans need to be on board to agree to put it to a vote. Speaker McCarthy’s concessions have bolstered this long-time agreement with the House Rules Committee now populated with several of the fiscal hawks. Since it is this committee that approves legislation that gets put to a vote, this could seriously delay the process of dealing with the debt ceiling.

What could happen if the ceiling isn’t raised

If the ceiling isn’t raised and the government runs out of money its first choice may be to suspend non-essential services and put some government workers on furlough without pay. The 1995 debt ceiling crisis saw 800,000 government workers furloughed for five days after a Republican-controlled House refused to back Democrat President Clinton’s budget and he subsequently vetoed the Republican spending bill. A temporary spending bill was passed, but this didn’t prevent another shutdown in December which saw 280,000 workers furloughed for another 22 days before an agreement was finally reached.

10Y Treasury yields fell by around 40bp during this period, but equities were left relatively unscathed given the minimal impact on GDP growth and only a minor, temporary hit to consumer confidence. However, the next crisis in 2011 led to much greater market volatility. Once again, a Republican-controlled House wanted deficit reduction as a condition for backing an increase in the debt ceiling. A deal was eventually done, but the fallout led to the US losing its AAA rating with S&P and the S&P500 equity index falling 17% between 22 July and 8 August. While workers weren’t furloughed, the economy saw growth of just 0.8% annualised in 3Q11, before rebounding 4.6% in 4Q11.

We have seen the furloughing of government workers on several further occasions, including twice during Donald Trump’s presidency after he sought funding for a border wall with Mexico, which came up against opposition from the Democrats. The last time was between 22 December 2018 and 25 January 2019, which was the longest government shutdown in history.

Eventually, one side has always blinked and a deal struck. We believe the same will happen again this time, but it is not guaranteed. In the absence of a deal, all expenditure, over and above what the government takes in from tax revenue, would have to stop. That means defence spending and social benefit payments face dramatic cuts and debt interest payments and redemptions stop, meaning America defaults.

What could happen if the government defaults

Technically, a default occurs when there is one missed payment on a bond, whether a coupon or redemption amount. The size of the missed payment is not the issue; any missed payment classes as a default. The reasons for this thinking are twofold. First, there is the legal reality that contractual terms have been broken. Second, one missed payment risks acting as a precursor to future missed payments. Allied with that is the notion of cross default, where a default to one bondholder can be construed as an implied default to all.

In most cases, default threats result in a pronounced inversion of the yield curve. Emerging market defaults have typically seen front-end yields pushed up into the 1000% area. This happens for two reasons. First, front-end bonds are most prone to default on the redemption amount due, as they are up next for payment. Second, low duration risk (low price sensitivity to yield changes) in short dates means that a decent fall in the bond price (can be 50% or more) must coincide with a huge rise in yields.

US Treasuries are a vital cog in the system, one that sets the global risk-free rate in the US dollar, acknowledged as the dominant reserve currency. Any significant damage to the credibility of US Treasuries must result in a fall in their value. In that sense, should a default tarnish the credibility of US Treasuries by enough, there should be a marked fall in the price of Treasuries. But, capacity to pay is there, as is the willingness, which should limit the damage. It’s just that politics temporarily frustrates this; that’s the nuance.

Assessing the damage from a possible credit rating downgrade

The preliminary risk is for rating agencies to downgrade in anticipation of the rising risk of default. The US is currently rated AAA at Moody’s and Fitch, and at AA+ at Standard and Poor’s. The natural reaction to a rating downgrade would be a fall in the price of bonds. Essentially, the quality of the product has been tarnished, now requiring a higher yield to entice investors.

That said, when Standard and Poor's downgraded the US in 2011 (from AAA to AA+), there was in fact a flight into the “safety” of Treasuries. So, while the product was optically tarnished, it in fact saw inflows as other risk assets took the brunt. In addition, note that credit ratings don’t always determine where bond yields trade. Consider Japanese government bonds. They’ve been trading in negative yield territory in recent years (although higher now), even though they are single-A rated.

So, while a (single notch) rating downgrade for US Treasures would reflect a higher risk of a technical default, any impact on Treasuries would likely be fleeting. Moreover, it could even result in Treasury yields falling if other asset classes were to bear the burden.

If the rating downgrade came from an actual default event, that’s a whole other story.

How bad could it be?

Typically, a missed payment and a technical default would push the credit rating of the issuer in question into sub-investment grade, and into a state of outright default should the issuer signal that it will neither make good on the missed payment nor on future ones. Such an extreme outcome for a single missed payment by the US Treasury is less likely, but not impossible, especially if the situation remains unresolved.

In such an extreme, a move into sub-investment grade would cause significant counter-party issues. There would likely be margin calls made to reflect changed valuations to Treasuries as collateral. Also, repo documentation might not all dictate a AAA rating on collateral, but the pricing of such trades is in part a function of the security’s credit rating, and this becomes a bigger issue should the collateral no longer be rated as an investment-grade product. The financial system itself would come under severe pressure.

In the case of a milder rating downgrade and an envisaged solution, holders of Treasuries, non-domestics in particular, would still tend to engage in liquidation in favour of other hard currency alternatives, at least as an impact reaction. Wider concern across the risk asset space would result in falls in equity markets and wider credit spreads, and these reactions could be quite severe to begin with. With price discovery made tougher, volatility would ratchet higher in jumpy markets.

This would result in higher funding costs for mortgages, autos and all types of consumer and business loans that operate at a spread over Treasuries. That is the most likely central outcome from a default, even if it’s a technical/temporary one.

Preventing a worst-case scenario

While the knee-jerk reaction to a missed payment for most issuers would be to place the issuer's bonds into a state of technical default, in the case of Treasuries, the reaction could be mitigated by the willingness of the US Treasury to make good on the missed payment, and on future ones. This would require a fast reaction from Congress to belatedly raise or suspend the debt limit.

It is probable that a missed payment would prove to be nothing more than a “mistake” or a consequence that has not been fully understood, where politics strays too deep into the slippage zone. This, more than likely, could be quickly rectified. Following a quick congressional resolution, investors would need to be made whole and compensated for the inconvenience and associated costs.

And then there is the Federal Reserve backstop. Technically the Fed could print US dollars to finance interest rate and coupon payments. The Fed would not be happy to do this on an ongoing basis as it would devalue the reserve currency status of the dollar and ultimately could destabilise the financial system.

Federal Reserve printing could be employed as a safety net though, where politics makes a mistake, and the Fed steps in as a payer of last resort. The Fed could rationalise doing so as a means of protecting the system. It could certainly soften the impact and indeed could prevent a technical default in the first place. However, this would not be a structural solution. Moreover, it poses its own independent threat to the financial system as the US dollar is undermined by monetary financing of the national debt.

In the extreme the system is threatened, which is why it should not happen

Even the smallest missed payment would be a huge deal, but we’d expect the market to view it as a technicality to be rectified swiftly. That could come from Fed prints. Or it could come from a quick reaction from Congress to get the ceiling suspended.

But if not, and a technical default morphed into, say, rolling missed payments, the system would likely collapse, bringing the economy down with it. This is a very unlikely outcome, as both the system and the economy would be caught in a highly flammable situation; one so damaging as to make zero sense.

And that’s why it won’t (or shouldn’t) happen.

Why a delay in debt suspension acts contrary to the Fed's QT ambitions

There is also a technical aspect to consider. The US Treasury currently has a $455bn cash balance at the Federal Reserve. This will get run down over the coming months as the Treasury spends more than it can raise through debt issuance.

The last extreme low was around $50bn in the first quarter of 2021 (at the conclusion of the previous delay in suspending the debt ceiling). A repeat of this will see some $400bn come into the system, adding to liquidity circumstances, effectively cancelling out the liquidity-reducing impact of the $95bn per month balance sheet roll-off currently being exercised by the Federal Reserve.

In a sense, delaying the suspension or elevation of the debt ceiling is acting to counter the Federal Reserve’s quantitative tightening ambitions, at least when it comes to how it affects overall liquidity in the system.

Debt ceiling will challenge benign FX market narrative

2023 has seen a benign narrative develop for the year, where easing US price pressures, China reopening and lower gas prices have prompted a rally in risk assets and a weaker dollar. As above, the prospect of a US sovereign downgrade or an unthinkable US debt default would clearly not be a core part of the 2023 investment thesis.

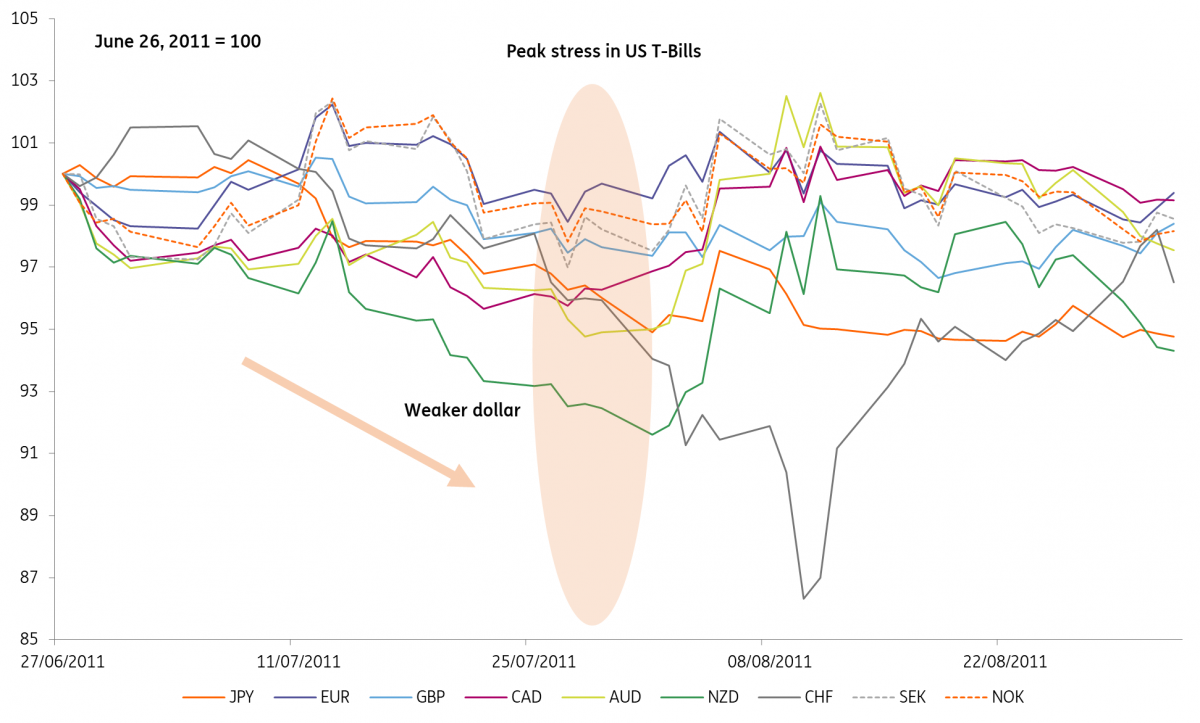

How would FX markets react? If past performance is any guide, we can look at the events of 2011. One measure to examine the peak pressure on this theme is a calendar spread on US Treasury bills (T-Bills). For example, as that summer unfolded, investors felt uncomfortable holding T-Bills expiring in August and demanded higher yields for August than for T-Bills expiring in December – when investors assumed politicians would have seen sense and the crisis would have been resolved.

Peak stress in that calendar spread was seen around 29 July, when investors demanded an extra 13bp to hold the August rather than the December T-Bill. As our chart below shows, the dollar was weaker through the month of July against all currencies in the G10 space, though somewhat surprisingly the Australian and New Zealand dollars briefly outperformed, before handing back more of their gains. Notably, the Swiss franc had some of the largest lasting gains around that period.

Back to today, US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has implied the US Treasury has enough money to pay its bills through June, suggesting that July/August could again be the period when this topic hits financial markets. There are no kinks in FX option volatility curves to suggest this event risk has been priced in yet, but nearer the time it would not be a surprise to see traded volatility priced higher. Equally, it would make sense that the defensive Swiss franc and Japanese yen would outperform against the dollar – and could see some sizable gains on the crosses rates should fears of a US debt default grow.

Dollar performance against G9 currencies during 2011 debt stress

Politicians crack…hopefully

The lesson from all this is that politicians are quite prepared to inflict pain on the electorate and the economy for their own political ends – remember the potential for default is not down to America’s ability to borrow, but the desire of politicians at a specific point in time to permit that borrowing.

Eventually though, fearing the electoral consequences of inaction, we do see concessions made and an agreement forged. But this time, more than any over the past 30 years given the ideological differences involved, the brinkmanship could be even more extreme.

The best-case scenario is that politicians see sense with both sides prepared to work on a deal over the next few months. Government workers and bond-holders would get a little nervous about whether they would be paid, but concessions would be made by both sides and the debt ceiling raised in time.

Unfortunately, given the political backdrop this looks unlikely. Instead, we run the very real risk that nearly a million government workers go without pay for many weeks thanks to extreme brinkmanship. This will be financially challenging with households already struggling with the high cost of living, and could result in marked expenditure cuts. The political stalemate also has the potential to last much longer than previous episodes and we could see even deeper cuts to government spending and the prospect of default, which would be both economically damaging and have major financial market implications as outlined above.

There have been proposals made that could get around a deadlocked Congress, including the creative idea of the Treasury minting a trillion dollar platinum coin and immediately depositing this at the Federal Reserve, which would give the government the funds to keep spending. Another is the president invoking the 14th Amendment Right to pay the government’s obligations, thereby overriding the debt ceiling. However, President Biden has made it clear that this is not on the agenda and in any case, there could be legal challenges to both.

Nonetheless, pressure will mount on the president to change his mind if Congress can’t strike a deal and these seemingly outlandish scenarios move one step closer to reality.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article