UK: Why inflation shouldn’t be an issue for the Bank of England

Like in the US, Britain is likely to see some pent-up demand emerge this year, as the economy reopens. But the corresponding impact on inflation is unlikely to be a major concern for the Bank of England. That suggests any tightening of monetary policy is going to be a 2023 story at the earliest

The UK will release inflation and retail data this week, and unsurprisingly with the country stuck in lockdown, both are likely to be relatively depressed. Headline CPI will remain heavily constrained by energy prices, while more timely spending data points to a post-Christmas 4% fall in retail sales.

But with reflation becoming a key theme in financial markets, it’s a good time to ask, will the UK see price pressures re-emerge as the country reopens?

Strictly speaking, yes. Headline inflation is likely to be back to 2% by the end of 2021, though unsurprisingly a lot of that is down to energy. We’ll soon be no longer comparing current petrol prices to the severely depressed levels of last spring. A 9% increase in the household energy cap, and the end of the hospitality VAT cut, will also both add upward pressure.

But will it last? We think probably not, and that for a few key reasons, inflation is likely to drift back below target in 2022.

The strong consumer recovery comes with caveats

A lot depends on consumer spending, and there’s little doubt there is pent-up demand waiting to be unleashed once the economy reopens on a sustained basis.

The UK savings ratio has spiked to 17% as of the third quarter, well above pre-crisis levels. And we expect this to help drive a strong recovery in output through the spring/summer.

But there are caveats - the biggest being that this rise in involuntary savings has disproportionately benefited higher earners. A Bank of England survey from last year indicated many of those on lower incomes have seen savings fall, no doubt linked to the higher rates of redundancies and furlough among these workers.

This is important, because it tends to be lower-income consumers that drive the biggest changes in overall spending - a point demonstrated clearly in the US last year, where high-frequency data showed the rapid recovery in consumer spending was led by lower-income earners (buoyed by higher unemployment benefits and stimulus cheques).

In other words, the consumer story is likely to be strong - but it potentially has its limits.

BoE survey suggests lower-income earners have seen savings fall

Stronger demand for services may not translate into higher inflation

Secondly, while the consumer rebound is likely to favour services over goods, the cost of these services tends to be fairly sticky.

In fact, despite the huge drop in demand for consumer services during the pandemic, core services inflation has actually been fairly stable. Once hospitality prices, which have been artificially depressed by a VAT cut, are removed, the rate of services inflation has stayed broadly in line with where it has been since 2018 (around 2%).

The same is likely to be true during the next stage of the recovery, though there will inevitably be exceptions. For instance, last year we saw haircut prices spike on reopening, though this was maybe down to PPE costs rather than higher demand. There’s also a case for accommodation to see a summer spike if foreign travel is banned.

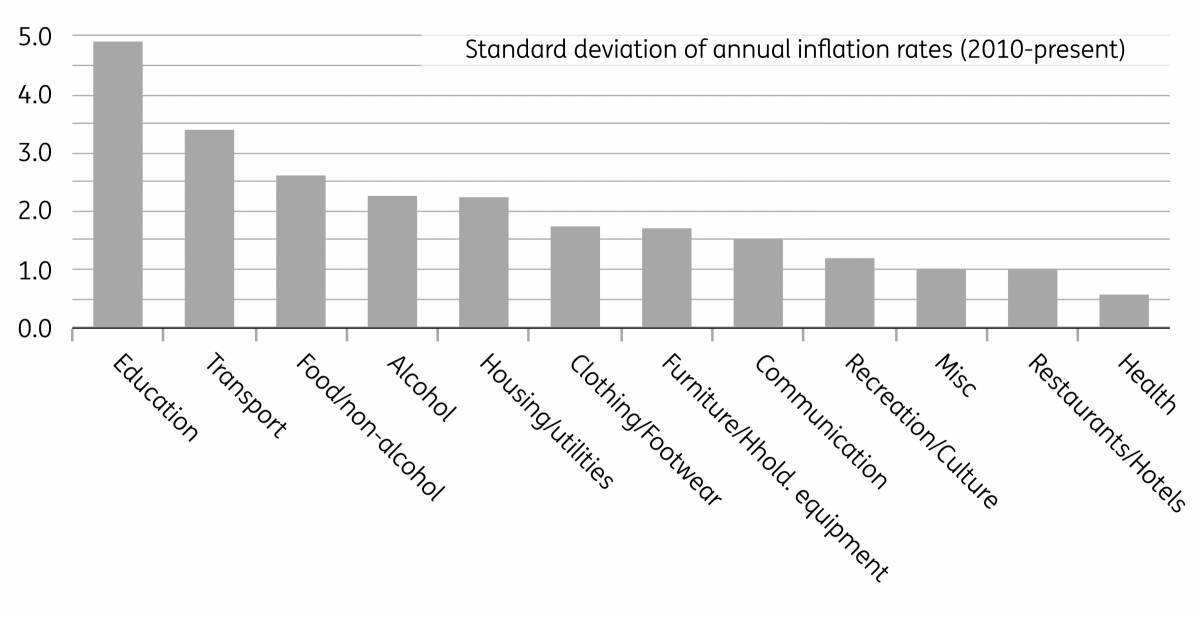

Otherwise, many consumer-facing services, including restaurants/pubs, are often fairly price-competitive - and the chart below also shows that hospitality and leisure price categories have historically experienced less volatile inflation rates.

Outside of hospitality, services inflation hasn't fallen through the pandemic

Hospitality prices tend to be fairly stable over time

The pandemic hasn't generated much inflation so far

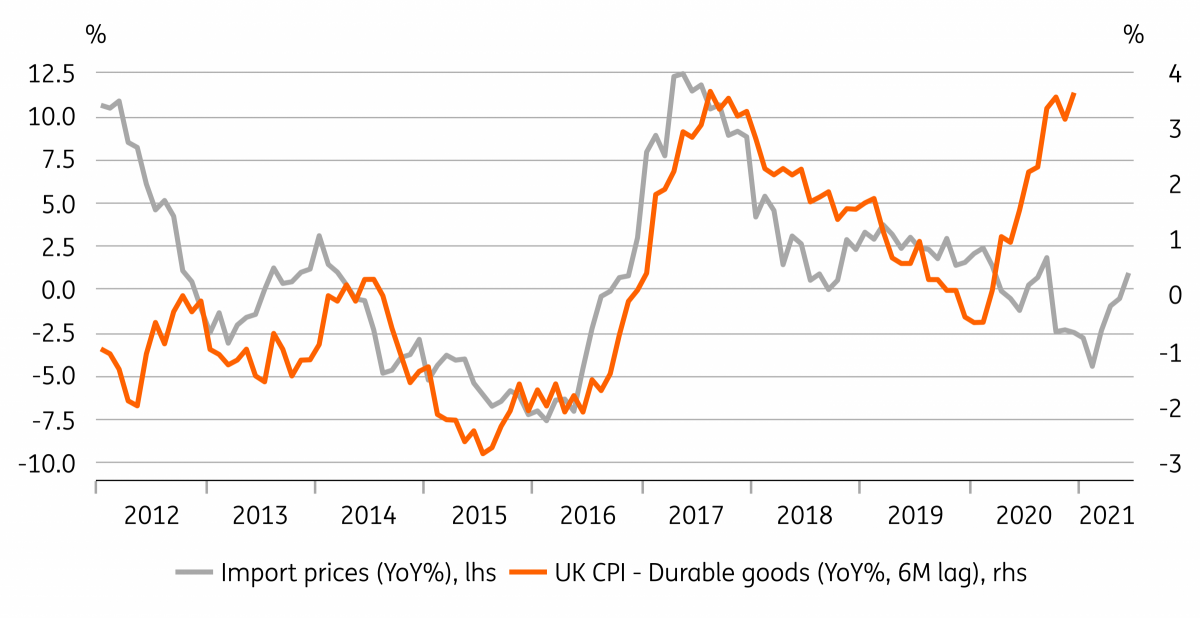

We can also draw some tentative conclusions from what’s happened to prices since the start of the pandemic. Consumers have spent more on goods than services last year for obvious reasons, and that appears to have helped push up the cost of things like vehicles, and household electronics. Durable goods inflation is running at 3.6% YoY, similar to the peak we saw after the post-Brexit collapse in the pound, only this time there was no real change in import prices.

There is also some evidence that retailers have been able to expand their margins. Prices of ‘core’ manufactured goods rose a little more quickly than producer output prices through last year.

But the impact on overall inflation of these demand-spikes has not been huge. Goods prices outside of some of those durable categories were typically stable or lower.

Durable goods prices have spiked - and this time not because of sterling

Jobs market slack means inflation unlikely to be a Bank of England concern

In short, we probably shouldn’t get too excited about UK inflation this year. But as ever, a lot will hinge on the jobs market, and how quickly it recovers after the likely unemployment spike we’ll see once the furlough scheme is wound down later this year. Either way, it’s likely there will be sufficient slack over the next couple of years to prevent wage growth from reasserting itself.

The major counterpoint comes from shipping costs, which have spiked over the past couple of months - both due to Brexit, but also worldwide container shortages. We will inevitably see the impact in consumer prices over the next few months, although in some cases retailers may find they lack the pricing power to fully pass these costs on, if we do indeed see demand pivot away from goods towards services.

From the Bank of England's perspective, the inflation story does at least suggest little need to press ahead with negative interest rates later in the year. Equally, it also suggests that any BoE tightening is unlikely to come before 2023, at the earliest.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Download

Download article