Turning tide? The Brexit threat to UK foreign direct investment

Businesses urgently need clarity, and a change of tack, from the UK government as they decide on current and future investments in the UK

The Brexit threat

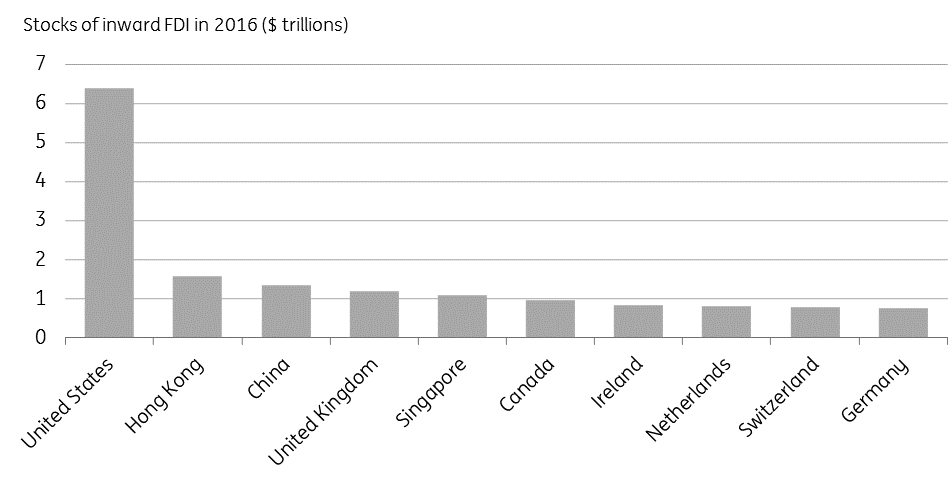

In 2016, the UK had accumulated the fourth largest stock of inward foreign direct investment (FDI) in the world, and the largest among EU countries (Chart 1). Several factors have contributed to the UK’s success in attracting investment, including the size and relative wealth of its domestic market, a flexible and skilled workforce, relatively low taxation, supportive government policies, and an entrepreneurial culture.

The finance, insurance and manufacturing industries have the largest stocks of foreign direct investment in the UK, and EU membership is of obvious importance to these industries. Firms located in London are able to benefit from networks of complementary functions situated in the City while exporting financial services across the EU thanks to ‘passporting’ rights. In manufacturing, frictionless trade underpins complex supply chains that allow firms to specialise. With each representing more than a quarter of the foreign-held UK assets, a significant amount of the UK capital stock is vulnerable to a deal which causes manufacturers and financial services to pack their bags.

The negotiations between the EU and UK have offered firms and investors little reassurance that these benefits will be preserved in the future relationship. Over the last week, there have been appeals to the UK government to urgently provide more clarity. Appeals from firms with complex supply chains, such as Airbus, BMW and Jaguar Landrover, have made it clear that their investments in the UK – and hundreds of thousands of jobs – are potentially under threat from the lack of progress in the negotiations.

Crunch point

A post-Brexit UK, we believe, belongs in the EU customs union and VAT area, and adheres to single market regulation for industrial goods. There is no doubt that this will be challenging to negotiate. However, it's the most realistic way of avoiding a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland, or in the Irish Sea. There are other benefits for both sides: the UK could keep its manufacturing industry, and both parties could avoid higher costs of trade in goods (in which the EU has a surplus).

Until now, the UK government has favoured leaving the customs union and the single market, and using technological solutions to minimise the resulting trade frictions. However, even a few minutes’ delay to lorries’ transit would see the roads to Dover and other ports, on both sides of the English Channel, blocked with queues. There is also the question of when the blow will fall, due to the need to develop and test the technology. Estimates of the time needed suggest at least five years would be needed, making the 20-month transition period inadequate, another source of uncertainty for firms.

A post-Brexit UK could do little to counter the downsides for UK manufacturing from a rise in trade frictions (less regulation, for example, would be a barrier to trade with the EU and other countries, too). The threat of no deal is still hanging over the negotiations, and could yet happen if the UK government cannot find a position to unify it. Manufacturers have seemingly reached a crunch point in their decisions. Their plea to government is not just to avoid a no deal outcome, but to change course in the negotiations.

While forcing the government’s hand in this way may bring some relief for UK manufacturing, it will do nothing for the City. As an issue belonging to the future relationship between the EU and UK, trade in financial services has not yet been dealt with in detail by the negotiators. A temporary permissions regime should come into play in the event of no deal. However, firms are eyeing the prospect of greater trade frictions and – unlike with manufacturing – the lack of a compelling incentive for the EU to minimise these in the negotiations. The direction of travel for new investment, and for future jobs, is toward Frankfurt and Paris.

Odds and indicators

With betting odds suggesting “no deal” is a 50:50 call, the need to manage supply chains differently and make preparations for disruption is showing up in rental yields on storage units, which are at levels more often associated with prime real estate. Uncertainty about the UK’s future relationship with the EU has already affected business investment within the UK, causing it to drag on growth. But foreign direct investment appears to have held up so far.

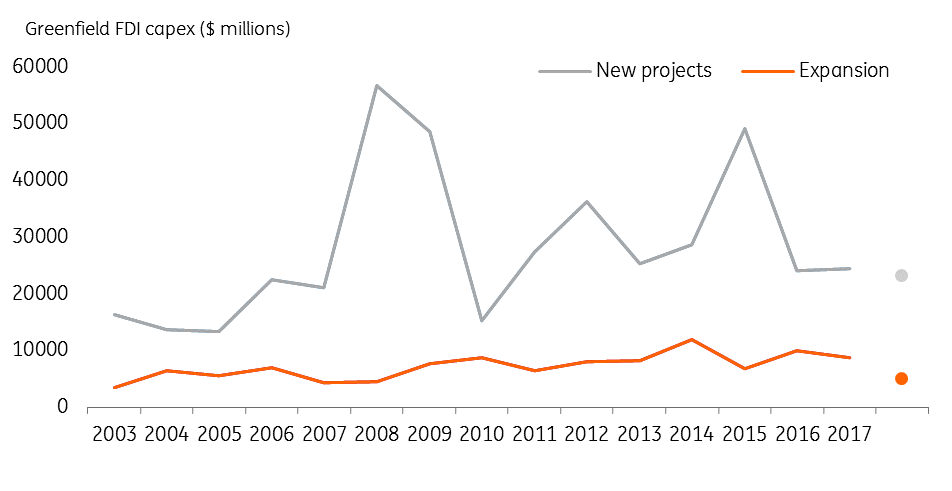

As the Bank of England noted on Wednesday in its Financial Stability Report, in 2016-17 there were substantial inward flows of direct investment (as well as other types of investment) into the UK, supported by the risk appetite in global markets. The latest data show a net inflow of direct investment in 1Q 2018 after outflows had consistently exceeded inflows in 2017 (causing the four-quarter sum of net FDI to turn negative in Chart 3). UK greenfield projects have continued to attract FDI. The total value of capital expenditure normally fluctuates from year to year, and during 2016-17 it has been in line with the post-crisis average, though lower than in recent years. Investment in the first half of 2018 points to some slowing in expenditure on project expansions (Chart 2).

Bank Rate and Sterling

At the moment financial markets are pricing in a 60% chance of an August interest rate rise from the Bank of England and this is our call too, but we see little to justify further significant policy tightening. The UK growth story is subdued and inflation could slow more quickly than the BoE anticipates given the peak of the inflationary impulse from sterling’s Brexit-related plunge has passed, and pay pressures remain muted.

However, should a future UK-EU trade deal generate significant trade frictions the risks to interest rates will be increasingly skewed to the downside. If FDI starts to leave the UK then jobs will be lost and unemployment will climb. The long-anticipated pick-up in wages won’t happen and there will be a shortfall in tax receipts, pushing up government borrowing levels. In such a negative scenario we could, in fact, see the Bank reverse its course on interest rate moves, compounding the downside risks for sterling.

The post-Brexit outlook for UK FDI is pivotal for sterling – especially if one views the pound’s external dynamics through the prism of the UK’s basic balance. We’ve previously noted that evidence of a broad ‘sell UK assets’ theme in global markets has been limited since the Brexit referendum – and in the absence of a material breakdown in UK talks with the EU, we expect this to remain the case.

But a ‘Minsky Moment’ for UK assets is a tail risk for GBP. In particular, if the prospects of a no deal Brexit resurface, then one could see both portfolio and FDI flows reversing – which would see all three factors in the basic balance pointing downwards (Chart 3). Sterling’s sharp post-Brexit decline implies that financial markets have partly adjusted to such a scenario, but we could well see sustained pressure on the currency over a period of time. Put alternatively, sterling is cheap – but cheap for good reason, and unfavourable external dynamics will keep the pound structurally weaker for longer.

Download

Download article29 June 2018

In case you missed it: Crunch time This bundle contains {bundle_entries}{/bundle_entries} articlesThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more