Treasury’s FX report preview: Taiwan and Thailand dangerously in “manipulators” zone

The semi-annual FX Report (the first one under Yellen) should be released in the coming days by the US Treasury. We estimate that in 2020 Taiwan and Thailand – along with the already labelled Switzerland and Vietnam - both met the three criteria (which might be loosened, reversing a move by Trump) and may be labelled currency manipulators

FX Report: Time to estimate the Yellen “touch”

The US Treasury’s semi-annual Report to Congress on “Macroeconomic and foreign exchange policies of major trading partners of the United States”, also known as the FX Report, is expected to be published in the coming days. It will be the first one under the new US administration and under the new Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen.

In our 23 March article “Taking a peek at Yellen’s foreign FX agenda” we discussed what key themes are set to be dominant for the new administration when it comes to addressing FX manipulation of US trading partners. In this article, we try to estimate the content of the Spring edition of the FX Report and what countries may either receive the manipulation tag or face advanced scrutiny by the Treasury by being added in the Monitoring List.

This week, some leaks about the content of the FX Report appeared in the media. First, it’s been reported that China will not be labelled a currency manipulator. This is not a big surprise considering that China only met one criteria when the previous report (in December 2020) was published and according to our estimates it should meet two at this edition of the FX report. If anything, we would have expected the criteria to be changed before China could have been labelled a manipulator, but we doubt that not labelling China as a manipulator (when not meeting the criteria to) should be read as a signal that the US is softening its stance on China’s currency and macro-economic practices.

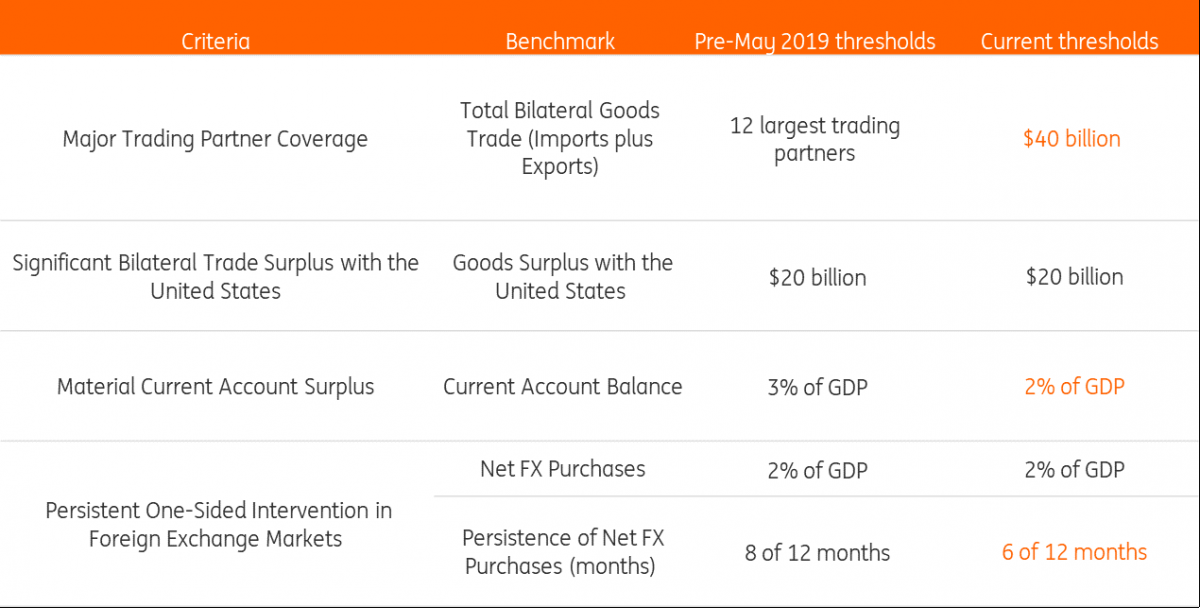

Second, it was reported that the Treasury has been discussing to revert to the previous (higher) quantitative thresholds that must be exceeded to meet the manipulation criteria. The thresholds were trimmed by the Trump administration in May 2019, which represented a turn of the screw on foreign FX mis-practices. The table below shows the current and pre-2019 thresholds.

Such change would likely be in line with the Biden administration’s tendency to unwind many measures taken by former President Trump. However, it surely runs the risk of conveying the message that the Treasury is adopting a more light-handed approach on foreign FX practices, and this would be in contrast with Secretary Yellen’s pledge to tackle currency manipulation. It will also remain to be seen whether the Treasury will only temporarily tweak its stance on trade and FX practices in light of the emergency situation caused by the pandemic in 2020.

Our estimates: Switzerland and Vietnam continue to meet all criteria

The spring edition of the FX Report takes into account data for the whole previous calendar year, that is 1Q2020 to 4Q2020. We attempt to replicate with our estimates the Treasury calculations that will be included in the Report, assuming that the criteria and the thresholds have been left unchanged.

It is important to note a few things with respect to such calculations. While the trade in goods (first criteria) is reported by the US Census and the current-account balance (second criteria) is reported by the IMF, so there should not be much room for divergence between our and the Treasury’s estimates, the method used to calculate FX interventions (third criteria) leaves a significant room for discretion.

The Treasury staff normally adjusts the changes in a country’s FX reserves by a valuation and macro-prudential factor, in an attempt to isolate the amount of FX purchases were effectively directed at curbing the domestic currency appreciation. However, it has often been the case that the local central bank unilaterally disclosed the amount of FX interventions to the Treasury (like the case of Vietnam and Thailand in the December 2020 report).

We attempt to apply a similar discounting factor as the one used by the Treasury to the increase in FX reserves as we estimate FX interventions, but considering the wide room for discretion, we normally imply a margin of error. In the case of some countries, FX interventions are reported as null despite an increase in FX reserves, simply because the local central bank does not engage in interventions.

In the December 2020 report, Switzerland and Vietnam were labelled as currency manipulators after they met all three criteria in the four quarters to June 2020. Unsurprisingly, considering how most economies normally active in the FX market increased interventions in the second half of 2020, Switzerland and Vietnam likely continued to meet all three criteria.

While Switzerland disclosed FX interventions worth CHF110bn (around 15.6% of GDP) in 2020, Vietnam is not publicly releasing such data, and has been providing the value of interventions privately to the Treasury in recent times. Given the unavailability of FX reserves data after September 2020, our estimates for Vietnam’s FX interventions are for the period January-September 2020. Still, we estimate that in that period alone Vietnam’s currency interventions were worth 3.1% of GDP, and considering that FX reserves jumped in 4Q20 across most Asian EM economies, it would be surprising to see Vietnam’s reserves bucking that trend to push interventions below 2% of GDP when the whole of 2020 is considered.

Our estimates: Taiwan and Thailand also in “manipulators” zone

The news that Taiwan would be included in the FX manipulator’s list has been circulating for some months, as the country’s large current account surplus and trade surplus with the US have been accompanied by significant interventions in the FX market since 2019, also through FX derivative operations. We thought that the Treasury already gave a free pass (by underestimating FX interventions) to Taiwan in December, possibly due to geopolitical considerations related to China’s influence in the region.

We estimate that Taiwan’s FX interventions in 2020 amounted to 5.8% of GDP, way above the 2% threshold, so the country would be significantly above all three thresholds and should be included in the manipulator’s list. This appears to be consensus now, and the Taiwanese dollar has already reacted to the news earlier this week. After all, the Taiwanese central bank Governor acknowledged that Taiwan may be labelled a currency manipulator in a speech in March, but minimized the risk for the economy from receiving such a tag.

As we saw for the case of Vietnam and Switzerland, the immediate implications of receiving the manipulator label are hard to spot in the short-term. The US Treasury must engage in a year of bilateral talks with local authorities before sanctions/export bans/tariffs may be applied. Surely, when it comes to Taiwan, the geopolitical aspect should remain a primary consideration as China-US relations are re-emerging as key global theme as most countries start to exit the pandemic crisis. If anything, sticking to a quantitative approach when it comes to identifying manipulators (so, sparing China and labelling Taiwan and Thailand) may suggest that the FX Report will have a smaller political connotation under Yellen than it did under Mnuchin.

What could be more surprising for markets is for Thailand to be tagged as a currency manipulator. We estimate that the country did meet all three criteria: USD 26bn in goods trade surplus with the US, C/A surplus worth 3.3% of GDP, and persistent FX interventions worth 2.6% of GDP in 2020. Like Taiwan, the country might have been given a free pass in December 2020, although the geopolitical motives there would be harder to identify.

We cannot exclude that the Treasury will spare Thailand again, or that it may simply estimate that FX interventions were actually below 2% (the Thai central bank may once again provide that information unilaterally), but if a strictly quantitative approach to the manipulation tags is indeed applied, Thailand appears at high risk of receiving the label. After all, THB – just like TWD – has remained deeply into undervalued territory versus the USD when compared to its PPP-implied exchange rate (as shown in the chart below) published by the IMF.

Even if the impact of the labelling is not significant in the short-term, when, if as we expect, the dollar bear trend resumes later this year, the close watch of the US Treasury will likely discourage some of the more extreme Asian FX intervention seen over recent years.

Monitoring list: China to stay, Mexico and Ireland to join

When a country meets only two of the three criteria, it is normally included in the Monitoring List, and will face closer scrutiny of its trading and currency practices. As of December 2020, there were ten countries in the Monitoring List: China, Japan, Korea, Germany, Italy, Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand and India.

Assuming that Taiwan and Thailand are named FX manipulators and considering a country is excluded from the list if it fails to meet two criteria for two consecutive Reports, we do not expect any of the listed countries to be removed from the watchlist. China was previously included despite meeting only one criterium, but the rise in C/A surplus to 2.0% of GDP in 2020 legitimizes its presence in the list.

Mexico and Ireland should be the two additions to the Monitoring List, as they both showed high trade surplus with the US and C/A surplus, but are safe in an FX-intervention perspective, so the market impact of being included in the list should be limited.

The chart below summarizes what we expect to see in the Spring edition of the Treasury’s FX Report.

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Tags

FX manipulatorDownload

Download article

14 April 2021

Good MornING Asia - 15 April 2021 This bundle contains 3 Articles