The second wave of debt: EU Covid-19 funding and market reaction

September sees the start of EU Covid-19 funding programmes. We look at the borrowing needs from various EU supranationals, the potential for ECB support along with the market impact. EUR supra will undergo a step change in borrowing and private investors will be required to buy most of the new debt. And we think they'll require cheaper valuations

Coronavirus response: EU supranationals are coming of age

EU and Eurozone member states have learnt their lesson from the previous crisis. If the monetary union is to survive the current economic shock, its response needs to be forceful and coordinated. Between April and July, member states agreed on a range of crisis-fighting tools to support countries with the least fiscal space. Most of these entail a degree of joint issuance from existing EU and Eurozone supranational entities. While these entities are already known issuers on the debt market, the new crisis-fighting apparatus means a step-change in the amounts to be raised.

Below, we detail our debt sale expectations from European supras in the coming years. We also discuss the implications for the EUR debt landscape, in particular the behaviour of traditional safe debt buyers and their possible market impact.

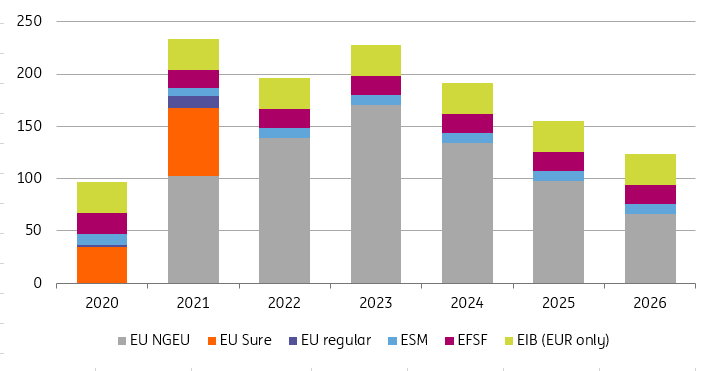

Estimated annual funding needs of European Supras (EURbn)

Source: EU/ESM/ING

The funding impact of the Covid-19 response on European supranationals

Around €1090bn in financial assistance has been made available by various EU entities In response to the coronavirus epidemic and its economic consequences. This should, in theory, require commensurate debt funding from European supranational issuers. We think debt issuance of around €800bn over the next six years to fund these programmes is a more realistic figure. Here are the details:

| €750bn |

Grants and loansvia the NGEU funded by the European Union |

EU: Next Generation EU (NGEU) and Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF)

The largest chunk of the €750bn is channelled via the NGEU. Under this umbrella, the RRF will make €312.5bn available in non-repayable grants and €360bn via loans.

As for RRF grants, the stated aim is to legally commit 70% of the funds in the first two years and 30% in 2023. Committing the funds does not mean they are immediately disbursed, however. In the proposed RRF regulation, the implementation period for RRF programmes was capped at four years for reform and seven years for investment plans. This suggests RRF funding needs could be spread across the next seven years. For our calculations, we make the simplifying assumption that grants committed in any given year are paid out evenly within three years. For instance, this means funds committed in 2021 are paid in equal parts in 2021, 2022, and 2023.

The RRF loans make up €360bn of the facility. The cap for individual countries is set at 6.8% of Gross National Income. Applying that cap to countries which could economically benefit from these loans, i.e. currently funding at more expensive levels than what the EU funds would cost, suggests a lower figure of €320bn. Again, Spain (c. €80bn) and Italy (c. €120bn) would be the largest potential takers and their decisions are thus a key factor in any calculations. Without any further information available we have assumed an equal distribution of €320bn in loan payouts from 2021 to 2026.

The EU summit agreement calls for 10% of the RFF to be paid in 2021. That would be just above €67bn in loans and grants and our estimation for that year is already higher. Regarding the exact timing of the first disbursements, though, the Italian finance minister had hinted that the 10% portion could be paid out already in the first half of the year with the approval of the countries’ investment and reform plans. More details on that are here. Regular flows from the RRF would begin only in 2H 2021.

Other grants under NGEU amount to €77.5bn. Again, we have distributed the funding impact equally over the relevant years for our illustration.

There is an additional factor that could lower funding needs: the so-called "absorption rate”. As some member states sometimes encounter difficulties complying with the conditionality attached to EU disbursements, the funds received can be below what has been committed. Since the majority of EU funds will go to eurozone countries, and since they tend to have the highest absorption rates, we have made the simplifying assumption that 100% of committed funds will also be spent.

With regards to funding strategy, the EU has detailed that it will issue bonds with 3Y-30Y maturities. Issuance will spread out so that within the repayment period, running from 2028 to 2058, no more than €29.25bn of principal comes due in a given year.

| €100bn |

Via SUREFunded by the EU, starting September |

EU: Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE)

€100bn in loans have been made available via this programme. The EU has already stated that it has requests lined up amounting to almost the entire €100bn. Loan applications processed so far add up to €85bn according to the commission but further requests from Portugal and Hungary are currently being studied and should push the total closer to the maximum available.

The implementation period for SURE runs until the end of 2022, but the EU has suggested that roughly a third could be funded this year starting in September and the remainder would be funded next year until the summer. According to the investor call, funding could take place in bimonthly syndicated deals, raising about €10bn per month.

| €240bn |

European Stability MechanismLoans available but no takers yet |

ESM - Pandemic Crisis Support

€240bn of loans are theoretically available to be called on by Eurozone nations. This is calculated on the basis of 2% of GDP per country cap.

Economically the loans only make sense for countries that themselves fund above ESM levels, which means only €80bn can be realistically called upon.

ESM credit line requests could have a degree of stigma attached

ESM credit line requests could have a degree of stigma associated with them. The ESM help deployed during the sovereign crisis was conditional on strict reform programmes. While the conditionality has been drastically reduced, that perception remains in some recipient countries. So far, neither Italy nor Spain has expressed interest in the ESM credit line. They alone would be eligible for almost €60bn in loans. If called, the ESM would pay out 15% per month of the maximum committed amounts. For our funding assumptions we leave the ESM pandemic support aside since no country has expressed an interest, but requests from smaller countries (the remaining €20bn) could become funding relevant in the coming months before the EU recovery fund kicks in.

EU could become the dominant Supra issuer over the next years

Oustanding bonds in EURs by currency. The shaded areas indicate the maximum possible envelope of EU and ESM funded Covid-19 financial assistance. For the ESM it is unlikely that the full capacity will be called.

Funding the regular operations of European supranationals

For the EU's established programmes the EU has flagged funding needs of €11.25bn for 2021 stemming from a rollover of EFSM loans and macro-financial assistance.

ESM funding for this year is €11bn with €4.5bn remaining and €8bn for next year. We have proxied gross funding needs beyond 2021 with bond redemptions, but keep in mind that early loan repayments can contribute to lower issuance needs.

EFSF funding for this year is €19.5bn with €5bn remaining, and €16.5bn for next year. Again, we have proxied gross funding needs beyond 2021 using the redemption profile.

Regarding the European Investment Bank, we have assumed for our purposes that the EIB will continue in the next few years with a yearly issuance of around €60bn across all currencies. Up to 50% of that could be in EURs although we would not exclude the EIB reducing that share in light of the upcoming EUR issuance from peers. Note also that one of the conclusions of the July EU council summit was to study the possibility of an increase in the EIB’s capital by the end of this year. This would increase its lending capacity, and thus its funding needs.

Debt buyers: If you build it, they will come

Having established the scale of the EU supranational debt issuance in the coming years, one natural question to ask is: who will buy it, and at what price? As was the case when EU sovereigns drastically boosted their borrowing at the onset of the coronavirus epidemic, there does not seem to be much concern out there about EU supranationals' ability to find buyers.

As we wrote at the time, the ECB's purchases due to expire in mid-2021 have been commensurate with the fiscal measures taken by sovereigns. This means reliance on private sector investors has been limited in aggregated terms to finance the fiscal response. In addition to direct debt purchases, ECB liquidity injections have provided banks with ample liquidity, some of it likely invested in government securities. Finally, the exceptional degree of risk aversion has also boosted other investors' demand for safe assets.

Supra debt sales to outpace ECB purchases, even with a PEPP extension

Timing is everything

One important difference between how markets received the new flood of sovereign and how they will deal with additional European supranational debt is timing. Whilst it is possible sovereigns will engage in only modest fiscal tightening in the coming years in order not to choke off the recovery, the vast majority of their debt increase is likely to take place in 2020 and 2021. What's more, the phase where this increase was the sharpest is likely to be already behind us and coincided with the phase of front-loading of ECB purchases to calm market panic.

As we have shown above, 2021-23 should see the greatest increase in EU supranational debt. With the ECB's net PEPP purchases due to stop by mid-2021, and with the incentive structure of its liquidity injection making reimbursements more likely from H2 2021 onwards, one can reasonably ask how relevant central bank support will be for the supranational market.

A significant contribution from private investors will be needed

Granted, an increase and extension of PEPP beyond mid-2021 would go some way towards boosting confidence the new supra debt can be absorbed, but a significant contribution from private investors will be needed. As we show in the chart above, the end of PEPP in mid-2021 means ECB net purchases would amount to roughly 30% of gross issuance from the four largest supranationals that year. A PEPP extension at the current pace until end-2021 means this figure would climb to 46%. Barring a further extension of PEPP, net purchases will drop to 17% of gross supply from the largest issuers in 2022. For comparison, the same ratio in the Mar15-Dec18 period, the first iteration of the ECB's QE, was 78%.

Private investors: the missing link

Even with an extension of PEPP, more than half of supra issuance will have to be bought by private investors. Much has been made of the shortage of safe assets in the previous crisis, and how common EU debt issuance would go some way towards easing this pressure. In our view, the relevance of additional EU supra borrowing for the path of interest rates at the macro level is fairly insignificant. For instance, we estimate gross Euro government bond issuance will reach €1.3tn in 2020 alone, compared to €233bn of gross supply from the largest supranationals in 2021, the year we expect it to peak.

Demand for safe assets in the coming years is a lot more difficult to map out than supply. We would simply stress that the need for government bonds and their substitutes (such as supranational debt) should decrease with economic uncertainty. We do not feel confident in calling such a change this year, but within 12-18 months we surmise that the case for owning safe debt would have weakened somewhat. Given that, unlike sovereigns, EU surpanationals will still be in a phase of accelerating net supply, this market segment should prove more price-sensitive.

A latter supply spike should cheapen supra valuation vs governments

This, we feel, makes current EUR supranational valuation relative to government bonds difficult to sustain. Using the Bloomberg Barclays indices for supranational and German government debt as guides, we find that a difference of 40bp between the two average asset swap spreads, compared to 25bp currently, would be more consistent with the supply surge the supranational market is about to experience. The last time this level was reached was in late 2018 when the ECB concluded its net asset purchases.

Given the scale of the increase in supra supply, this may seem like a fairly minor change in their pricing relative to government bonds. One factor that we feel should prevent further cheapening of EUR supra debt is that the increase in size would make it more attractive for investors with a strong preference for liquid assets, such as large reserve managers. We also expect investors that are roughly indifferent between the two assets classes, such as banks' liquid asset portfolios, to increase their holding in supranational debt if they cheapen towards the top of their recent range.

Download

Download articleThis publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user's means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more